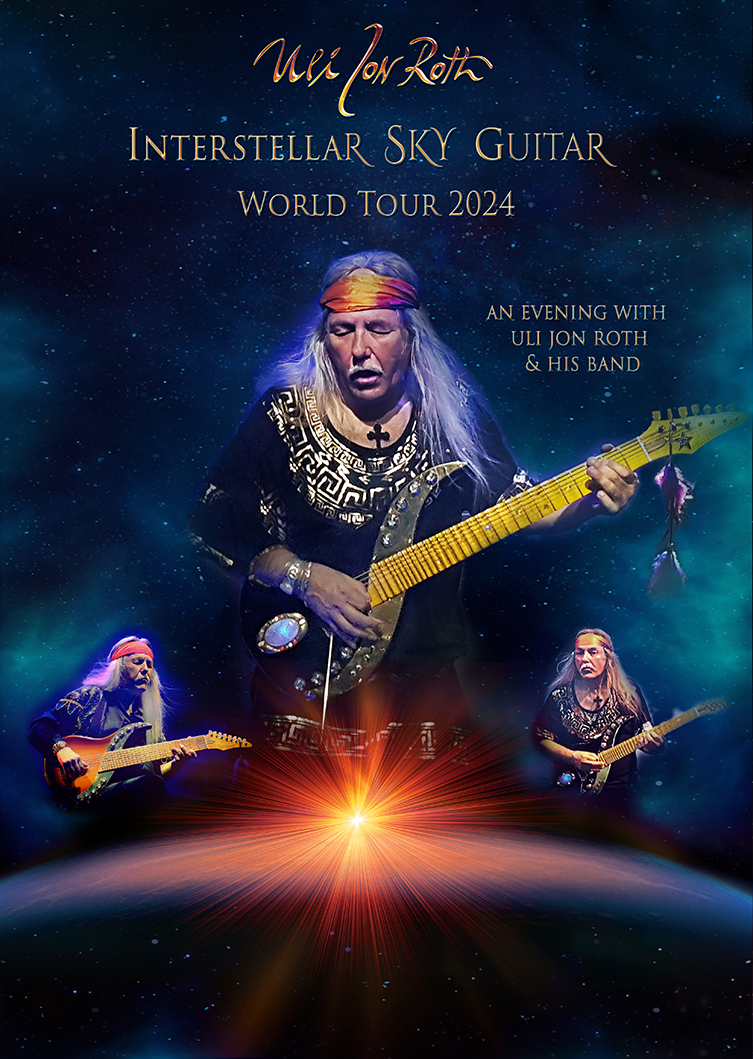

"When I Do Music, I Don't Exist: Nothing Else Exists" Uli Jon Roth talks EXCLUSIVELY to guitarguitar!

It’s a clear and frosty Saturday morning in November when I get off the train at Irvine, a town on Scotland’s Southwest coast. Down the road a little from here, the neighbouring town of Troon is in the middle of hosting this year’s Winter Storm festival, a three day celebration of all things rock. There’s a distinctly classic/melodic slant to most of the bands on the bill, and armies of denim-clad rockers have made the pilgrimage from across the country to settle here for a music-fueled short break. Later on in the morning, I’ll follow the ‘battle vests’ covered in Iron Maiden and Judas Priest patches in order to check out the Winter Storm venue down by Troon beach, but in the meantime, I have a good reason to be one town further up the coast.

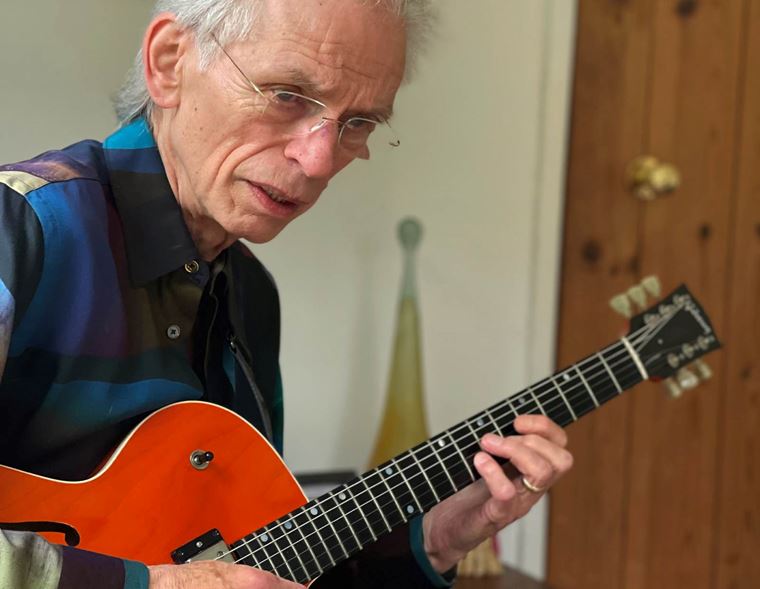

(Photo courtesy of Uli Jon Roth)

Here is where ex-Scorpions guitarist, philosopher and electric guitar pioneer Uli Jon Roth is staying after his headlining performance the previous night. Now, it’s not everyday that such a musical giant can be found in such Scottish seaside towns, so I was excited to make the most of his visit by arranging to travel through for an interview.

Uli Jon Roth has been a highly revered and influential player since the mid 70s, when The Scorpions brought their potent brand of rock to the world. Familiar sounding enough to be popular on the radio, yet different enough (largely thanks to the guitars) to make a unique mark on the world, the Scorpions quickly became a household name amongst hard rockers and casual music fans alike.

Uli parted ways with the band a few years later, not out of acrimony but due to a desire to follow his muse into ever more neoclassical and mystical musical locations. He’s followed that path ever since, pushing what’s possible with the electric guitar in both rock and classical contexts. He has developed the Sky guitar - a concept that features extra frets, strings and proprietary electronics - to help facilitate his adventures, and has branched out into special training/development weekends known as the Sky Academy. He’s a man who seems to truly be in sync with his own self, his abilities and his creativity.

As synchronicity would have it, the Scorpions’ Sails of Charon had recently been popular on the guitarguitar office radio, and I’d actually committed myself to learning the jaw dropping intro guitar solo. This was weeks before I’d made the connection that Roth would be performing in Troon, but once that connection had been established, it felt like destiny was stepping in to give a helping hand. What is it they say: when the student is ready, the teacher appears?

We join the story as Uli leads me to his hotel room to hold the interview. Sat at a glass coffee table, I can look out the patio doors to a bright, frost-tipped lawn, with the ocean a few hundred yards further off. Uli sits down, and I press ‘record’ on my handy recorder…

Contents

Sky Academy, Alpha Waves and Mental Blockages

Uli Jon Roth Interview

Guitarguitar: One of the first things I would love to know about - if we take Sails of Charon as an example since we were talking about it - that, for me, was a real game changer. In 1978...

Uli Jon Roth: Written in ‘77.

GG: In 1977, okay. That was probably one of the first times that a mainstream audience heard this exotic type of non-blues guitar playing.

UJR: Completely not blues based!

GG: Exactly! Even before we get into where your inspiration may have come from, did it take a level of bravery - if that’s the appropriate term - as a guitarist for you to jump out with such a style?

UJR: Bravery is not the word. I was always, I guess, a natural born explorer, driven by one half curiosity, and on the other by, dare I say it, vision, you know? So, you see something in your mind and the far distance like a vision, and you want to do that. You have no idea how to do it but you kind of zone in and get closer. It was a little bit like that. This guitar lead for Sails of Charon didn’t write itself! I was conscious that I was pushing the envelope there. Nowadays it’s really easy for me to play, but back then it was a bit of a challenge because I had to find the technique to do it.

(Photo courtesy of Uli Jon Roth)

The tonality is classical, basically: it’s Harmonic Minor, you know? The song is in E minor technically, but it sounds like B major throughout: there is no E minor in the song. Nowadays we are actually ending it on E minor but the E minor is constantly only implied. It is the root, but it is like a hidden eminence in the background. In flamenco, B, C, D,that’s it, you know? So, it wasn’t - classically speaking - anything unusual but in rock music, I guess, because it was in those days, as you said, very blues based and riff based. Genuine classical thinking, you wouldn’t find that in rock. I was at that time doing exactly that: bringing the classical vocabulary - which had been there for centuries - into the rock world on the guitar. Keith Emerson had already done that, but that was on the keyboard, a completely different domain that guitar players didn’t respond to. I'm generalising, but there’s a lot of truth in that, those were two different worlds, you know?

GG: Certainly.

UJR: So, I guess if I did anything new, then it was just that I brought that into the language of the guitar. For me, I knew that was a new step because I didn’t hear it anywhere else, but at the same time, it was very obvious to me because I wanted to hear that! I thought, ‘why is nobody doing that?’ Nobody was playing diminished arpeggios, now every schoolboy does that at a hundred miles an hour! Back then, nobody did it. Django Reinhardt already did it, and Charlie Christian, but in rock, nobody cared about these people: these names were never mentioned. It was always the same names: Hendrix, Clapton, Beck and later on Ritchie Blackmore. There were a few players who were a little more daring, like Jan Ackermann, he was absolutely great, a trend setter. But then he left Focus and you didn’t hear much any more. That was a couple of years before me. Nowadays he doesn’t get any credit for that, but he should: he had a fantastic tone and feel, he was exceptional.

GG: You mentioned a classical influence. One of the main things I think about with that classical crossover would be Genesis, but then that was much more often on the keyboards.

UJR: Yeah, that was a completely different world. Genesis was never a guitar band as such. Their strong point was harmony and chords, I never classified them as a melodic band.

GG: That's a good point.

UJR: It was atmosphere and harmonies, you know? Not so strong on the rhythmical front, but it was that world, harmony. And Yes, they had it all. They were completely unique of course: fantastic bass player - Chris Squire, my favourite - the combination between him and Rick Wakeman and the various drummers, and Jon Anderson and Steve Howe was totally eclectic. It was just completely unique: there will never be another band like Yes. And I have to say, I didn't really get anything from Yes into my personal vocabulary, but I found them a very inspirational band to be around, particularly Relayer. The Gates of Delirium was unbelievable, with Patrick Moraz.

But yeah, you’re right: none of these things really spilled over into the guitar playing world, which was quite insular. I had a feeling that there wasn’t that much progress being made at a certain point. Ritchie Blackmore had taken it as far in that one way where he brought a little of the minor into it, and a little of the classical touch, but it was still largely pentatonic-based, riff-based.

And then, I would say that Michael Schenker and I were the next generation. We did bring different elements into it.

GG: With those classical influences, and the elements you were drawing from, were there particular composers or pieces that spoke to you more?

UJR: Yeah, completely. I started on the bass, then started on the electric guitar. At first, I learned by ear, listening to Eric Clapton and co. Slightly later, it was Jimi Hendrix but Clapton was first. That’s how I got my original vocabulary, with Bluesbreakers and great stuff like that. Very soon after that, I discovered the classical guitar and flamenco. At the time, Manitas de Plata was the leading flamenco player whim I saw in convert in 1970 or 71. Then I started to gravitate more towards classical guitar and the classical repertoire. When I was 15, I did pretty much nothing but that! I was in a band called Dawn Road, a high school band, but my main practising time was on the classical guitar studying Bach.

"When I do music, nothing else exists: I don't exist. That's the most important thing"

That’s where my heart was, but at the same time, I discovered the world of violin playing, and started listening to the big violin concertos: Brahms, Mendelsohn, Tchaikovsky, Beethoven, the big concertos. That opened a completely new dimension and I thought: ‘That’s what I want to do!’ On the guitar, you know? Later I bought a violin and learned how to play it, just in order to be able to write orchestrally for string instruments. I thought somehow that I wanted to hear the guitar soaring with these beautiful melodies and harmonies, and I didn’t hear that in rock music. Rock music was much more rudimentary, channelled to the ground - except for Jimi Hendrix, who took it to hyperspace! That was different: he was not really like a guitar player, he was more like a force of nature, just a great artist. I saw that, and learned an awful lot from him.

The other side was, I started to study these violin concertos. I got the music because I knew how to read music, and I started to transcribe the violin parts to the guitar. That was difficult because the range of the guitar didn’t allow that. It just went to the top C# on the Strat: if you bent the notes, you could just about get the top E, which in the violin is nothing, you know? (laughs) Then what about all the rest? It didn’t exist. That was frustrating, and that’s why eventually I came up with the Sky guitar.

So, this was my progression, you know? I never listened to a lot of rock bands: I just didn’t feel drawn to it, although I felt at home playing the genre. I knew how to do it, but I didn’t get much out of listening to other bands. My education pretty much stopped with Hendrix, Clapton, a little bit of the other bands afterwards. Then Jeff Beck came with Blow by Blow, that was quite an eye opener, not only for me but for many people. But that’s really where it stopped for me, and afterwards I just went on my own path and explored. It was an easy exploration because whenever I take the guitar and pick it up, I come up with a new idea. It’s always like that, it just pours out like that, and if I spend time on it, I can take it to all sorts of levels, but I don’t tend to do that nowadays. There was a time when I did though, and thought ‘how much further can I push it?’ I ended up doing Vivaldi’s Four Seasons on the guitar and wrote my own Metamorphosis concerto, which set the bar quite high for myself! (laughs) I had to actually start practising again to be able to do that.

Eventually, I figured it out and it’s all usually in the fingering: once you get the right fingering, anything becomes possible. You sometimes have to find very unorthodox ways of doing it, because the guitar is a very illogical instrument. A piano is completely logical, every note is where it should be; on a guitar, you can do the same thing in five, six, seven different ways! And you do, because each one sounds different. That’s the strength of the guitar: the incredible amount of diversity, colour and expression that you get on no other instrument. Not even the violin, definitely not the piano. Technically, these are more proficient and more easy to master in a way, but the guitar will sound different in the hands of every single player. You can really make your own voice with it, and that appealed to me. That, and the fact that it was completely uncharted territory, I felt also. I thought, ‘why is nobody doing that?’ It seemed so obvious.

Hendrix & Rembrandt

GG: You’ve touched on a few points I’d love to go back to, actually. You were mentioning about rock being in its rudimentary phase, and Hendrix was particularly different. I’m going to put forward the idea that it was his attitude and his intention that separated him from a lot of other guitarists.

UJR: Yeah.

GG: And obviously Hendrix was big for you, but I’d still say that you have a markedly different sound. So, my question is: is it important, when you have people who are linchpins for you, that you don’t copy people as much as you carry their spirit and their intention and apply that?

UJR: Well, you know, this is the ultimate goal of the natural progression of something. But there’s nothing wrong with copying. When we are an infant, we copy our mother to speak, we copy our parents to walk etc, you know? Little kittens watch their mother and copy them, that’s how we learn, and that’s how I learned. I learned by ear, figuring out these albums, and I copied them note for note. Never mind the individual touch, it will come very quickly. No matter how much you copy, you’ll always end up being you, and the stronger your personal artistic spirit is, the more you will become yourself.

Some people, they end up like copycats and they don’t add anything of their own because maybe they don’t have their imagination strongly developed, but a real artist will always break free from the initial stage of copying and very soon start to give his or her spirit free reign, and then new things emerge. An artist, in my book, is defined very much by the fact that an artist is able to do new things. Of course, nothing is completely new, but there are new combinations, and yes, something is actually completely new.

"Jimi Hendrix took it to hyperspace: he was not really like a guitar player, he was more like a force of nature"

Jimi Hendrix brought so much to the table that was completely new. At that time, nobody had ever even remotely heard a sound like that, or playing like that. Yes, he came from the blues but he far transcended it, and he came with a message: every note he played, whether it was good or bad - and they were sometimes bad, when he was in a bad mood - every note had an impact and a message. There was always an image behind it, and it was encapsulated in the note. People who had half an ear were able to maybe not fully decipher that, but they got ‘yes, there is something different here’. Back then, everybody got it. Everybody noticed that Jimi Hendrix had something to offer that other people didn’t have, it went way beyond.

(Photo courtesy of Uli Jon Roth)

Nowadays, young guitar players very often don’t understand Jimi Hendrix because he wasn’t flashy and not glitzy by today’s standards. He never played an arpeggio, and a young kid might define guitar playing by technical proficiency: how many scales you can do at what metronome speed (laughs). But that is of course an extremely immature point of view. If you look at great artists, yes there were some, also in painting, who were complete technical masters like Leonardo Da Vinci and Michelangelo, but you also have some who were technically quite weak! Van Gogh, for instance, but what an artist! He had such a powerful artistic spirit that shines through. Never mind the quality of his brushstrokes! What comes through is the general vibe and the image.

It was the same as Jimi Hendrix. He was a real master at what he did, and his playing was 100% technically for what he wanted to explore, but it wasn’t about being fast, flashy, this or that; if you’re looking for that, you don’t go and listen to Jimi Hendrix. He was about something completely different. And, he was such an outstanding - I don’t want to say songwriter because he maybe didn’t even write songs, he was more like a composer - every single one of his main tracks was decidedly different. Purple Haze couldn’t have been more different than Little Wing; couldn’t have been more different from Voodoo Child; couldn’t have been more different from Star Spangled Banner; couldn’t have been more different from Drifting, Third Stone from the Sun and last but not least, Band of Gypsys' Machine Gun. They are all masterpieces in themselves and they don’t follow a blueprint. Axis: Bold as Love is a fantastic piece of music, and completely unorthodox in both writing and lyrics, but what a masterpiece!

"I think like a painter when I play. I always try to emulate Rembrandt with brushstrokes. When I play a guitar lead, I see these brushstrokes in front of me"

So, to me, that’s what defines a great artist. Most musicians don’t even come close with any of that. If they even write one song which is on that level, then they can count themselves lucky! Hendrix just poured them out like the Beatles. Yeah, it wasn’t as commercial as the Beatles - the Beatles had a broader impact with a broader public - but it was certainly on the highest available level. And he will not be forgotten. In a hundred years’ time, people will look back and they will not remember many, but they will remember Jimi Hendrix.

GG: Maybe your comparison to those old Renaissance painters isn’t such an inappropriate one, when you consider the legacy.

UJR: I do that all the time! I think like a painter, when I play. I always try to emulate Rembrandt with the brushstrokes, To me, when I play a guitar lead, I see these brushstrokes in front of me, and that’s what I want: that 3-D, creamy, warm…and the older I get, the warmer I want it. Not always getting it: it depends on the amp, etc etc.

GG: I totally know what you mean. Not that this is about me, but you know Caravaggio?

UJR: Of course!

GG: His use of light…

UJR: Yes, that’s chiaroscuro! Rembrandt perfected that in a softer way. Caravaggio is very hard, very brutal, but a brutal genius, yeah.

GG: Brutal genius is a good way to put it! (laughs)

UJR: To the point of even killing someone. I think he did.

GG: He did, apparently so, yeah. He might even have been killed by the mafia afterwards.

UJR: That, I don’t know. I don’t think the mafia existed then.

GG: No, they’d be called something different back then, but those Italian crime families. Now, you mentioned writing for classical instruments and for Metamorphosis and so on. One of the main differences with a guitar is the tuning, because a violin, viola and cello are all tuned to fifths, and a guitar is in fourths, which created an entirely different situation for your left hand.

UJR: It’s not just that: the guitar is tuned in fourths and a third.

GG: Yeah.

UJR: That’s nigh on insane! (laughs) You look at a guitar and your finger patterns are changing. On the violin, everything is predictable, it’s exactly where it should be. On the piano, it’s singular: every note is there once. It doesn’t get any more logical than that. The guitar is basically a completely confusing instrument to start with. When I play the guitar, I really switch off my logical thinking. On the piano, I switch it on. I think on the piano I’m more like an architect; and the guitar, the Rembrandt brushstroke It’s just pure emotion and you feel your way through the muddle of it I picture the notes before I play them, I can see them in my mind but the guitar is really a minefield. But I wouldn’t have it any other way! Because I think that it greatly adds to this instrument being so different. And of course, when it comes to chord changes, that tuning makes an awful lot of sense, in terms of being able to do most chords reasonably logically.

So, I’m sticking with that tuning, except for my 9 string flamenco guitar. My bass strings are very unorthodox and I do the tuning for different reasons, to open up different key changes.

Sky Guitars

GG: Okay, that sounds like a good time to talk about your Sky guitars. Now, I’m putting words in your mouth here, but I’m presuming - given what you said - that you got to a point when you found limitations with the Stratocaster.

UJR: I found that very early on. I remember during In trance, we were tuned to E flat, and the maximum note I could get was the top E flat by pushing the string to its upper limit. That was high back then: you didn’t hear these notes on the guitar, apart from with slide players. Once I started composing my guitar leads, I thought: wouldn’t it be nice to go a third higher? Or a fourth higher? And you couldn’t!

So my solution was, in the days of Electric Sun, after Scorpions, so in the early 80s, I asked a guitar builder to give me two extra frets on the Strat, and he did. It worked perfectly, so my Electric Sun albums from Fire Wind onwards already had the slightly higher notes: I was able to go to the F#. That was good, but that was only a small beginning. That was the bridging moment, because the guitar builder in Brighton - Andy Demetriou was his name, he lives in Cyprus now - he was very good and he did a great job on that white Strat of mine. After he saw how pleased I was, he said ‘Look, I can build you any guitar you want!’ He literally said that. I’d never ever thought about questioning the integrity of the Strat up to that very moment. And then I thought, you know…any guitar…and that’s when I completely abandoned traditional thinking and started to question everything.

I knew I wanted a guitar that could do everything a Strat does, but I also wanted a guitar that can sound like a Les Paul, and a Strat can’t. So that was quite an unachievable thing to start with, for many different reasons. The initial phase was that I came up with the shape for the Sky guitar and he built the first Sky guitar. That was in 1983, precisely forty years ago now. I never went back, you know? We built five prototypes over the years, including two 7 strings, and those were the first 7 strings in rock.

GG: Prior to the (Ibanez) Universe?

UJR: Yeah. And then we didn’t build for twenty years. I always played Mighty Wing - the fourth Sky guitar, the 7 string - which was a unique instrument, it’s still unique. And then eventually, several people came up with the idea to put the guitar on the market. I heavily resisted that, because I didn’t want the guitar commercialised. I thought, no, this is too personal for me. Eventually, Elliot Rubinson, the then-owner and CEO of Dean guitars - now deceased, managed to persuade me at a trade fair. He kind of explained that I would be able to do more experimentation etc etc and I went with it. We became good friends, and he also started playing bass for me when we played in America, and for Michael Schenker. Ne was a great guy.

(Photo courtesy of Uli Jon Roth)

We put a limited edition of 50 Sky guitars on the market, all hand-built by Boris Domennget in Germany. That was my condition, because the original builder didn’t build any more, he had some back problems, so I found that one guy who was able to build them. Several people tried to build Sky guitars and they all failed dismally! None of them managed to do it properly: Boris did. From the first one, he was onto a winner. He’s my absolute favourite and to this day, he is building Sky guitars for me.

"We built 5 prototype Sky guitars over the years, including two 7-strings, and those were the first 7-strings in rock"

After the 50, Elliott unfortunately died of a brian tumour, a big tragedy because he was really one of my best friends and a bit of a mentor when it came to business things. Afterwards, somebody said ‘just do your own Sky guitar’, and after a while, I said ‘yeah, that’s what I’m gonna do’, because I am still able to do prototypes. Now we are building them to order, just selling them on the internet and they cost an arm and a leg but they’re worth it. He can only build so many per year, it’s not that many, and most of them are in America and Japan. Some people have 6 Sky guitars, they get addicted to them. I am, I don’t want to play another guitar. We have this super-sophisticated sound system in it which is called Megawing. It’s all-singing, all dancing and allows me to control any amp from the guitar beautifully with a gain stage, and has a very sophisticated EQ done by John Oram, the designer of Trident mixing boards, a master of analogue EQ.

So yeah, these guitars are just phenomenal to work with. I’ve played them ever since.

Blowing Up Amplifiers

GG: I don’t know if this is a bit of a basic question, but when you went to an extended range on both sides - so higher frets and additional lower strings - did you ever encounter any problems with amplification or EQ in terms of those extra frequencies?

UJR: No, good amps can handle it. My main amp for live is the 100w Blackstar Artisan, which is a very unforgiving amp. Most people cannot get a sound out of that! It’s based on the old Plexis but it has way more clarity on the bass end and is nigh-on indestructible. I like all these aspects but it’s like a beast, it’s hard to control. You need to know exactly what you’re doing, but with the Sky guitar, it works.

In the studio, I tend to use an array of amps as well. Most of the time, I will record with seven microphones and seven different setups, also in different rooms simultaneously. Then I can pick and choose. Some of them are small amps, including the AC30 which I love for the sound, but for live it wouldn’t be so good for me. My guitar, if you play it on high gain, an AC30 only lasts for half an hour and then it blows a gasket (laughs). So does the Fender Twin. A 5150 lasts about half a minute: I blew up two in a row, sounding great in the process particularly before they die! Fender Bassman: beautiful tone, and they last about half a minute. So I learned the hard way that certain amps I can only…because my gain is only 80dB or so, coming from the guitar like a keyboard, so I learned the hard way that with certain amps, I cannot drive them hard, I can only at a maximum pull them up to 50% capacity and they have all their headroom. So, now I don’t blow up amps anymore, but initially there were many casualties!

Mind you, the Marshall Plexis and the Blackstars and these modern modelling amps, they seem to have no problem with the high gain, you know? It’s just certain old-school amps that really don’t like it.

GG: I didn’t realise about the seven different setups in the studio, that’s pretty incredible!

UJR: Yeah, I’ve done that for a long time, yeah. I don’t use all the microphones, though. I tend to end up with a mixture of the ones that I like and then set them up and spread them across the panorama, you know?

GG: Sure.

UJR: My recording techniques have undergone various transformations over the years. In Electric Sun, I was using two microphones: a U47 far away, four metres away in a large room like in Olympic studios; and a Neumann U87 a metre away. No close mic. I never liked the sound: it’s too in-your-face and too ugly. So that was always my tone, just those two mics. Live, we will use the SM58 because that’s just a completely different thing, but you never get the full sound live anyway. It’s always a compromise.

GG: Sure. Gain’s an interesting thing for me: levels of distortion and so on. Live is indeed different from the studio, but I typically think of your sound as being not massively distorted…

UJR: No, not at all!

GG: …but still full of sustain and volume. Do you use much in the way of pedals then?

UJR: Not much. Recently, if I want an extra bit of singing, there is one pedal from a guy in America called King of Tone.

GG: Oh yeah, Analogman.

UJR: Yeah. I tend to use that. It doesn’t interfere with the timbral qualities of what you’re got. I don’t turn my amps up a lot: I have no master volume, and sometimes I have my volume on two or three, but because of the gain on my guitar, I can make the amps sing. Then when I turn down, I can have this super clean, 3-D sound that you’d maybe get from a Fender Twin and so on. Any other setup, you wouldn’t be able to get any of that: it would be either/or, or you’d have to switch channels and I don’t like that: I don’t like switching channels, the change is not organic. I like the approach you have with an orchestral player: when you have your violin, you have your pianissimo, and by altering your bow and putting more pressure, in the end you have fortissimo. I like exactly the same on the guitar: seamless transformation of tone from super clean to completely singing.

(Photo courtesy of Uli Jon Roth)

Also, when I play rhythm, I will go back and play the rhythm very often with single coils - with my middle pickup, say - and when I play lead, I very often go into humbucking because nowadays I prefer the sound more creamy. There are a lot of my fans who are constantly imploring me to go back to the Strat - but that’s not going to happen - because they like that super-aggressive clean sound that I used to get in Tokyo Tapes. I can still get that sound if I want to, but I don’t want to because my mind is different now.

And back then also, what they don’t realise is, it may sound great on an album but when you are standing in front of the amps back then, a hundred watt Marshall cranked to 11 with my wah pedal down all the way, on my poor non-humbucker single coil Strat, it was brutal! I only survived because I had ample amounts of cotton wool in my ears from my early youth! That’s why I’m one of the few who still have good hearing in the business, you know? I inflicted pain and suffering on all the people in the front row (laughs), but my ears are still intact, God forgive me! We used to call it ‘the death ray’.

(Photo courtesy of Uli Jon Roth)

Also back then I played with an enormous intensity. My strings were that high (indicates large gap between frets and strings), it was virtually unplayable. But, because they were so high, I was able to play fortissimo and really get every note as a life-or death scenario. You can hear that when you listen to those albums, but I don’t play like that any more. Sometimes I still do, for the occasional moment, but I prefer a creamier, warmer tone now, and so that’s what these fans from the olden days want. I understand where they’re coming from: they think it’s the guitar but it’s not. I can easily get that sound on that (Sky) guitar, but it’s my thinking. I can make that sound - I have Sky guitars that are Alder, also - and if I go to my single coil pickup, it sounds like a superstrat.

"Most of the time, I will record with seven microphones and seven different setups, also in different rooms simultaneously. Then I can pick and choose."

Anyways, it’s just one of these things that I wanted to clarify, because it comes up a lot these days. And yeah, I admit sometimes in the past there were some phases in the late 80s or early 90s where I was going through some stages of trying lots of amps and setups. Sometimes my live tone was not nearly as good as it should've been, and when people listen to live recordings of this period, they ask ‘Why does Uli play with such a shite sound?’, and I can’t blame them! I was going through all these phases of trying hundreds of amps, and this and that, but that’s long gone. Nowadays when you come to my show, you can expect a top-class guitar sound 95% of the time. Maybe not every night, because sometimes it’s just impossible.

GG: Sometimes it’s out of your hands.

UJR: Exactly.

GG: When you were talking about the dynamic range you have on the guitar, one of the things that I suppose is important is the guitar pick that you use, and your particular technique with it. Do you have a favourite?

UJR: Yeah, I use a Fender Extra Heavy and sometimes I have even heavier picks like these completely heavy ones, triangular. I use all sorts of shadings. Sometimes, I will really play pianissimo, very lightly. Sometimes I do a double attack where I’m blocking the string also with my fingernail while picking. That gives you an extra dimension to the sound, a 3-D effect and certain harmonics. I will sometimes alter the angle of playing: when I’m playing very fast, it will sometimes be a more traditional 90 degree angle; very often I have a 45 degree angle which gives you a creamier tone because it’s more like a brushstroke.

Most of that I do instinctively, but when someone asks me and I analyse it, that’s pretty much what happens, you know?

Sky Academy, Alpha Waves and Mental Blockages

GG: Yeah, it comes naturally. Moving on to the Sky Academy, and this idea of a deeper connection to music: I think about your music and playing as being this really good match between technical ability and creative impulse and creative freedom. Now, technical ability is something that I would argue you can probably achieve by working at it…

UJR: Yeah, if you work on it the right way. I always practised very efficiently, so I didn’t need to practise much! Yeah, because I’m doing it in an efficient way. A lot of people are just noodling around for hours and not getting anywhere because they are just not doing it right! (laughs) Because your body and your mind are instruments too. That’s the first thing you need to master. It’s all in the mind. The hands will do whatever you like, they are just an extension of your mind. A lot of people are having a lot of obstacles within themselves and these obstacles, these mental blockages are very hard to get rid of. It basically interferes with every note you’re playing, it’s holding you back. Get rid of all that stuff, have a completely free mind like a zen monk or someone like this, and then everything becomes very easy.That’s really it. You know, I learned that very quickly, very early on and I understood that. That’s why I’ve never really needed to practise much, and when I practise for short amounts of time, I get great results very quickly. It’s because of that, because I don’t have any blockages in my mind. It goes straight through.

GG: Are you talking about a sort of meditation practice?

UJR: Ah, I used to meditate a lot when I was younger, around the time when I wrote Sails of Charon for instance. That helped me a lot. Now I don’t need that any more: I’m always in that kind of mind - which I call the Zone. Alpha waves: my brain - most of the time - is tuned to Alpha waves, which is slow. So the everyday thoughts, most people’s brains work on Beta waves every day from 12 Hz to 30 Hz most of the time. You start thinking about ‘Oh, I need to check my bank account; is there food in the oven; I need to feed the cat; what did I say yesterday?’ All that kind of stuff.

With music, that’s the last thing you want. Your mind needs to be completely free from all that, like a still water so that you can see to the ground forever. That’s what I do when I do music: nothing else exists. I don’t exist. That’s the most important thing: you don’t exist. You just become ‘it’. No questions asked. So free yourself of all the mental rubbish and neuroses, all that kind of stuff. When I grew up, I had neuroses, but I got rid of all of that by the time I was 21 and then I was free.

"Get rid of the mental blockages, have a completely free mind like a zen monk, and then everything becomes very easy"

It almost sounds like Scientology, but it isn’t! (laughs) I’m not into that, but yeah, my mind became free, and that reflected in the music. It’s hard to explain. That is what my book is all about, In Search of the Alpha Law. That’s what Sky Academy is all about. I try to help the students to get to their own next level by opening up those channels that are blocked and then of course, the guitar is a great tool - music is a great tool - to heal yourself. We all have certain problems in our minds, our hearts, our souls: nothing is ever perfectly right, but the aim or the goal should be to be aware of these things, deal with them and not make it a hindrance towards your music making. That can be like a two-channel thing. By - dare I say - ‘cleansing’ yourself from all mental rubbish and things that don’t really matter, by concentrating on the things that do matter, which we need to find out for ourselves what it is, and using the guitar almost like a tool to connect - with music, certainly - but we can also connect with our own selves and both things will benefit.

(Photo courtesy of Uli Jon Roth)

Suddenly the scales that were difficult to play are suddenly easy, because you’re not in the way anymore. You are not the obstacle anymore, you know? That’s why people say ‘Oh, you make it look so easy!’ I’ll say ‘It is easy!’ I know it isn’t easy, but it is easy once it has become easy and once you personally don’t make it difficult. Approach it like a child: a child finds most things easy to learn because a child has such an open mind. Quite practically open. Like water, it’ll flow to the point where the exit is, just through gravity. Just let it be and don’t ask any questions. Just do it!

GG: Yeah, don’t provide any barriers.

UJR: Yes. And so that’s really it: if there is a secret to all of it, that is a big one. Music can actually teach you all these things if you allow it to. If you are connecting deeply with music - which a lot of people don’t do, you know? A lot of musicians, they love music, but they don’t really connect with music on the deepest level. The music is more like a drug that they inject and they inject it on a superficial level. It doesn’t really go deep into their heart and soul. The result is, that what comes out the other end in terms of their music making, is sometimes less than satisfactory, and maybe not touched by inspiration. It’s more imitation, which is an ok thing as I said before, but it’s only a beginning. The imitation is only a beginning and then from there on, the tree needs to grow and you need to make it your own tree, and bear fruit eventually. If it doesn’t bear fruit then it’s not much good!

(Photo courtesy of Uli Jon Roth/Dawn Belotti)

Postscript

Uli was certainly in the mood for sharing, and I felt it a particular privilege to be the sole audience to his thoughts that morning. I found Uli to be a very pleasant, interesting chap with a keen perspective on every question asked. It may be an ancillary detail to the main body of the interview, but this last anecdote is perhaps an effective way to illustrate his character… Upon hearing of my struggles to learn the famous Sails of Charon solo, Uli happily offered to show me exactly how to perform it. Jumping up, he put on his Mighty Wing Sky guitar, waiting for my phone camera to begin filming, and patiently showed me exactly how he plays it, even slowing down and re-playing some of the trickier points. ‘It can only be played one way, and one way only’, which turned out to be right, of course. Showing him my ‘official’ sheet music for the piece, Uli laughed and cried out ‘This is all wrong! It’s not even in the correct key!’ (the notation, not the tab), before signing my sheet and adding a little message to the transcriber, whomever that might be.

And then I was off, back into the bracing winter light of a coastal November morning, to follow the denim and leather crowds on the Ayr train as they pursued their own dream day of hard rock.

I had a wonderful visit with Uli, and would like to thank him for his generosity of spirit and knowledge. It’s certainly a morning I’ll remember for a long time. Thanks also go out to Akasha Roth for all of her help, and to Guido Leidheuser for all of his.

For all of Uli’s activities, including details of his forthcoming book, new gig dates and Sky Academy events, please head over to the official Uli Jon Roth website.

Thanks for reading this exclusive guitarguitar interview, and for over 150 more (including interviews with Joe Satriani, Steve Vai, Steve Hackett and many, many more), click through to the guitarguitar Interviews page.

See you next time!