What is a Floyd Rose?

Whammy bars are great things until they throw your guitar out of tune.

Again and again. No matter what you do, the merest twitch of your hand towards the bar results in one or more of the strings deciding to be ‘difficult’. Even for the most experienced of guitarists, this situation can be demoralising, to say the least.

Back in the late 70s, one man got fed up with this and decided to do something about it.

His name was Floyd Rose.

His Name Was Floyd Rose

We should probably say ‘is’, rather than ‘was’ since Floyd is still fully alive and kicking, just as when we say, ‘what is a Floyd Rose?’, we should really be saying ‘who is Floyd Rose?’, but this story isn’t about semantics. It’s about an invention that revolutionised not only the guitar as an instrument, but the very way people played it. The Floyd Rose tremolo essentially invented a new genre of music, and with it a new vocabulary of sounds. Join us as we head back to a semi-mythical time in the past, when rock was hard and ‘indie’ wasn’t a thing. Let’s go to California in the late 70s...

Van Halen, Not the Eagles

Let’s get our vision of late 70s California straight here, people. We’re not talking about the drug-addled, sausage-haired phoney cowboys who roamed Laurel Canyon. We’re talking about the mean, flamboyant and aggressively playful bands from out of town who would swan into Hollywood and pretend they lived there as their bands touted for gigs on the Sunset Strip.

We are talking about the glory days of Shred.

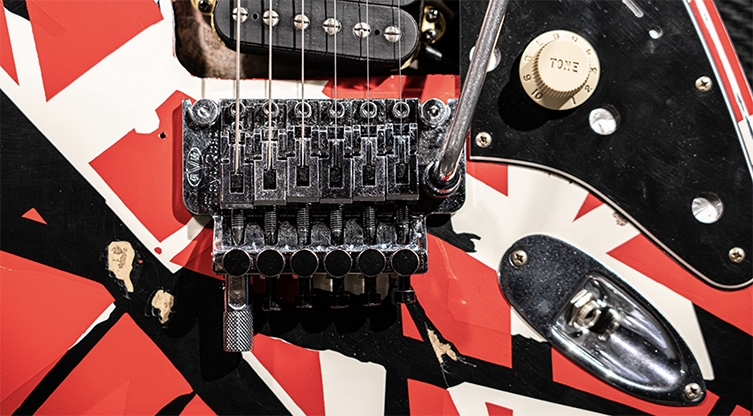

By the time the 80s swung around, the story of the Floyd Rose tremolo would be in full swing, so to speak, but in the late Seventies, lots of hotshot guitarists (a young Edward Van Halen would be one of their number) were coming up against the limitations of Fender’s whammy bar design from the 50s. It was just never intended to create more than a gentle wobble, and so more spirited use was pulling the guitars out of tune. Electric guitar pioneers like Hendrix and Ritchie Blackmore made glorious sounds with their Fender whammy bars, but even they suffered the ill fortune of tuning problems. Floyd Rose, a gigging guitarist in Southern California and jewellery maker by trade, was similarly frustrated. An avid whammy bar user, he grew fed up with this intolerable tuning situation and, in 1976, set about changing it once and for all.

The Plan Goes into Action

Using tools from his day job, he experimented with various systems that would solve the conundrum. Knowing that the strings moved back and forth through the nut creating friction (and thus creating potential tuning problems), he thought up the notion of a nut that would lock the strings in place, thereby stopping the movement dead and providing the much-needed stability. He got to work and soon had a prototype.

For the bridge itself, early models were not too distant from Fender’s traditional design. This makes logical sense, given that the bridge alone is not the sole guilty party in causing tuning discrepancies. Indeed, a combination of any of the points in which the strings came into contact with another surface during their travels could be a part of the problem (and indeed solution). Therefore, the bridge, bridge saddles, nut and tuning gears were all contenders for change.

Floyd’s first completed design certainly held down the strings at the nut, but it didn’t have a locking mechanism at the bridge. This unit was made from hard steel, after experiments with brass found that it wore down too quickly. The steel lasted and still had enough mass to ensure tone wasn’t sucked out of the guitar.

The first few units found their way into the hands of top local players like Eddie Van Halen, whose feedback proved significant in developing the Floyd Rose tremolo into the double locking monster we know today. As well as the idea to lock the strings at the bridge (in addition to the nut), further feedback brought about the fine tuners at the bridge. This was the masterstroke, given that strings would otherwise have to be perfectly in tune before being clamped down at the nut. Any tiny deviation from true pitch could not therefore be corrected without unlocking all of the strings and starting all over again. Hassle! This input from the top flashy players of the day meant that Floyd was able to refine his design and release a credible and legitimate solution for whammy-frenzied players who needed stability in their lives.

Enter the Floyd

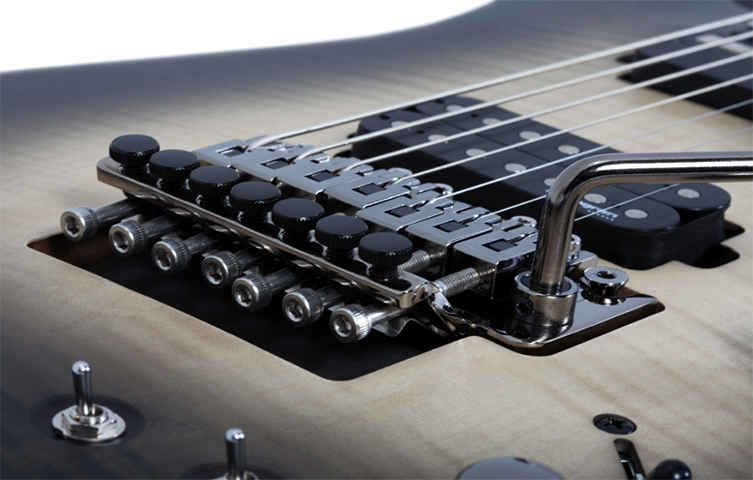

The final, revised unit was a large and intricate mass of steel machinery that looked like it meant serious business. It’s the same awesomely monolithic thing you see on countless guitars today, since Floyd got his design pretty much right on target. Variations exist, as we’ll mention later, but the majority of the device is as it was back then.

Looking at the bridge, each string sat with in it’s own industrial looking saddle. Each saddle had a powerful steel clamp to ‘bite’ the string and hold it in place. This biting action was achieved with an allen key, which had a socket at the tail of the bridge for each string. The unit itself operated in the same ‘knife-edge’ manner as traditional tremolo systems, but the locking nut up at the headstock (tightened by the same allen key) meant that once the strings were in place, and were properly stretched in (a rookie error, always), then they would not budge out of tune. A set of small fine-tuner thumb rollers above each string clamp allowed minute changes in tuning to be made, partly to compensate for the ‘bite’ of the locks pulling the strings sharp but also to concede that strings do stretch a little during their lifetime.

One significant factor in the design that threw people a little was the fact that you needed to remove the ball end of each string before it went into the bridge to be clamped in place. This was a simple matter of grabbing some snips and beheading the string, but some people found it an extra layer of hassle. Regardless, once the headless string was placed in between the jaws of the saddle clamps, the jaws could be closed on the string using the allen key interface at the back. Tight, but not too tight!

In operation, the Floyd Rose tremolo worked spectacularly well. The tuning held, even under extreme duress, which was now made more possible than ever, given the ‘routing’ behind the main bridge area (the wood was taken away from the body, an idea of Steve Vai’s) which allowed dramatic amounts of up-bend. The opposite direction – pressing down on the bar - brought about the famous/notorious divebomb sound, where the guitar’s pitch could drop lower than any realistically discernible note value. Indeed, the strings could be made to go completely slack, falling off the fingerboard entirely, before returning perfectly to pitch when the bar was returned to ‘neutral’. Guitarists had never seen or heard this type of thing before.

It caught on.

Success

By the mid 80s, guitar manufacturers were falling over themselves to have Floyd’s tremolo design on their guitars, thanks to the influence of Mr Van Halen and a certain Steve Vai, who’d already taken the sonic possibilities to wild extremes on records with Frank Zappa and Alcatrazz (as well as ‘replacing’ Eddie as guitarist in David Lee Roth’s solo career). Hair Metal had become a huge cultural phenomenon, and hit singles from all over the world (and not just hard-rockin’ tunes, either) featured squealing dive bomb sounds made possible by the Floyd Rose tremolo’s extreme pitch-shifting abilities.

It was no longer enough for guitarists to give their notes a gentle, Hank Marvin-like wobble, not when they could easily make their guitar sound like an air raid siren! Even Hendrix couldn’t coax the type of sounds now possible from a guitar. A new vocabulary of lead guitar playing was developed that used dramatic, atonal shrieks and screams as much as it incorporated fast, breathless playing. Shred was born, and guitar changed forever.

These Days

That was the 80s. In today’s musical climate, we maybe don’t hear as many Floyd Rose guitar wails as we used to, but they are still hugely popular with many guitarists. Predictably, it is the more technical and heavy sounding players who have always gravitated to the more ‘out there’ possibilities presented by this piece of gear. Today, most major manufacturers produce guitars with Floyds, though it’s fair to say that most of these are S-type guitars.

As for the tremolos themselves, there are actually lots of different varieties of Floyd Rose units out there. At a glance, they are very similar, since they all adhere to Floyd (the man)’s patented design. This includes bridges like Ibanez’s Edge series of trems. Contrary to some beliefs, these are still licensed Floyd Rose tremolos, just like those that you’d find on other brands of guitars. Ibanez make them in-house, and they do look a little different, but they are licensed Floyds none the less!

You’ll find Floyd Rose Special bridges on more affordable guitars, Floyd Rose 1000 models on more upmarket instruments and Gotoh-branded Floyd’s on top end instruments. The main difference is in the material (stainless steel for the most expensive since it literally takes centuries to wear down) and in the production method. Cheaper, licensed Floyd Rose tremolos are ‘cast’ (i.e. made from a mould) and more upmarket models are machined from individual blocks of metal, making them more difficult and expensive to produce, but hopefully stronger and longer lasting. Divebombs will be available on all varieties!

Benefits of a Floyd Rose

- If you stay in one tuning, you’ll (pretty much) never go out of tune.

- You can perform a large range of sounds that are impossible to create otherwise.

- You can achieve everything a standard tremolo can do plus a lot more.

- You don’t have to drastically change anything about your playing technique.

Drawbacks of a Floyd Rose

- Changing your tuning is a major hassle that requires re-setting the bridge entirely.

- Drop D tuning is not a thing for you now unless you install a ‘D-Tuna’ and give up on all notion of up-bend (raising your notes via the whammy bar).

- Changing strings requires more tools (snips and an allen key) and takes longer.

- Fresh strings still take a while to settle, which can be annoying when working with locking mechanisms and fine-tuners.

- If it’s there, there is always the temptation to over-use it...

Great Floyd Rose Moments

We’ll end our look at the mighty Floyd Rose tremolo today by running through a few of the device’s most celebrated practitioners. These players can describe what a Floyd Rose does better than any number of words written by us. Who knows, maybe you’ll get some inspiration to experiment with one yourself?

Eddie Van Halen

We may as well begin our little list with the man who tore up the rulebook and re-wrote it! Edward Van Halen is easily the world’s most influential electric guitar player apart from Jimi Hendrix, and this great live video form the mid 80s is a great way to show his energetic, effervescent spirit. Jump 2 mins in for the start of the UFO-noises!

Steve Vai

New Yorker Steve Vai took Eddie’s whammy vocabulary and ran with it down some eccentric and colourful alleys! His playing has always been regarded as some of the most inventive and flat-out impressive of any rock player. This performance of Bad Horsie begins with divebombs and brings all sorts of sonic chaos, mixing precise musicianship with a little taste of madness.

Joe Satriani

Joe Satriani is one of the most famous guitar instrumentalists on the planet, mainly due to his ability to marry winning melodies with brazen guitar histrionics in a way that’s palatable to non-guitar fans. We’ve picked Ice 9 from Satch's seminal Surfing with the Alien album here, since it contains a number of gravity-defying Floyd Rose techniques, notably the ‘lizard-down-the-throat’ sound, which you can hear at just before the 2min mark on this live video.

Dimebag Darrell

Pantera’s phenomenal axeman gave us lots of incredible leads, most of which were accompanied by at least one or two of his famous harmonic screeches from his Floyd. As you’ll see in this close-up video, Dimebag liked having the bar sit away from his hand, pointing backwards, so that a downwards push would raise the pitch of his note.

Tom Morello

No stranger to unusual noises, the famous Rage Against the Machine guitarist’s entire style is routed around unorthodox techniques. Using his ‘Arm the Homeless’ partscaster on this track, Morello makes a riff out of a very precisely played dive-bomb, taking what others would save for the solo and making it his lynchpin. Hang around for the 'mad monkey/robot' guitar solo to hear Tom really pushing things into a 'new' dimension...

Wes Borland

Talking about using divebombs for riffs, none are as blatantly effective as this crushing riff in Limp Bizkit’s frankly bizarre song here. Now, before we go any further, there is a huge amount of bad language in this tune (vocalist Fred Durst helpfully counts them for us in the song’s lyric: good guy) so if that sort of thing offends you, you may have to choose to miss out on the inarguably fantastic guitar riff here. Childish stuff? Without doubt. Fun? Absolutely! Great riff? One of the best.

Get Your Floyd On

So, there we have it. We hope the notion of a Floyd Rose tremolo makes sense to you know, and that you are maybe even tempted to try one out! They take a little bit of maintaining, sure, but that sort of sonic power doesn’t come without its responsibilities! We think the compromises are more than worth it. The Floyd Rose tremolo changed guitars forever and it is still a potent weapon for expressive noisemaking.

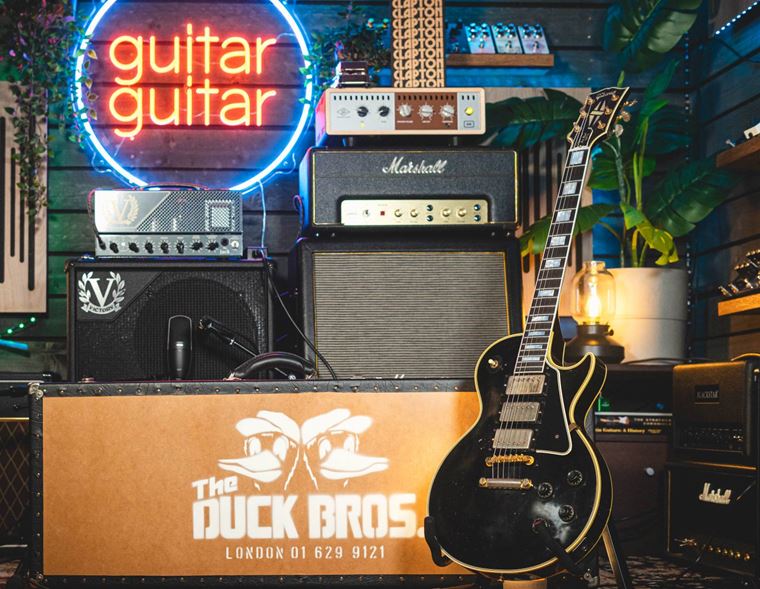

At guitarguitar, we have a great many guitars available fitted with Floyd Rose tremolos. Check out Jackson, Charvel, EVH (Eddie Van Halen’s own brand of guitars), Ibanez, Schecter, Solar guitars, ESP and even certain PRS & Fender models. There’s a whole world of sound out there just waiting for you.

Ray McClelland