TESSERACT Talk Portals, Bass and More!

There are whole universes of music within Tesseract’s 20 year career as a cutting edge band. From airy soundscapes to the most crunching of contemporary metal, these progressives are artists in every sense. Blending Progressive Metal with the concepts of science and metaphysics, the Milton Keynes five-piece have, over the space of 4 albums and 3 EPs, carved themselves a niche in modern music that’s theirs alone.

As part of the same modern prog-metal scene that includes bands like Periphery, Leprous and Monuments, TesseracT are no strangers to the world of ‘Djent’ riffs and complex polyrhythms, but there’s much more going on here musically than just that. Deep, hypnotic and dramatic, TesseracT’s music makes the most of dynamics, atmosphere and surprise to deliver top-drawer modern guitar music with more than a hint of ‘the cosmos’ about it!

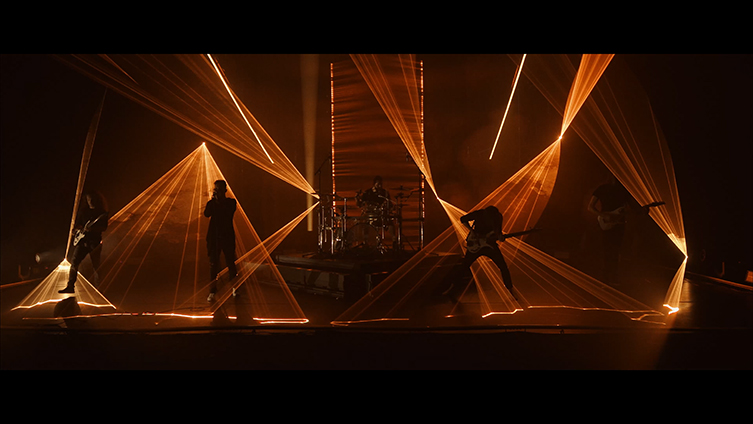

(Photo: Steve Brown)

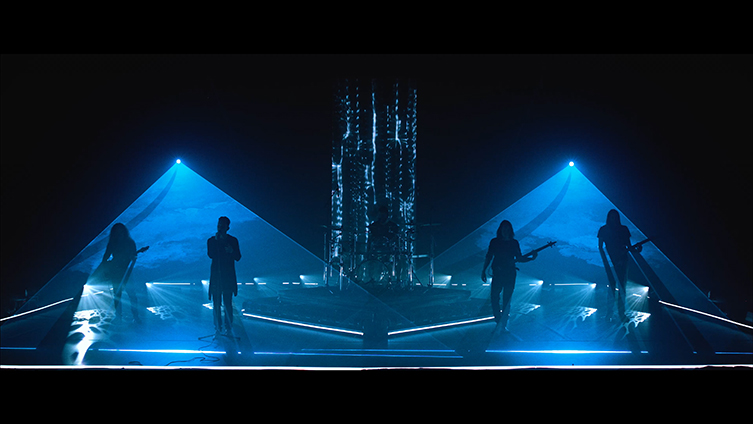

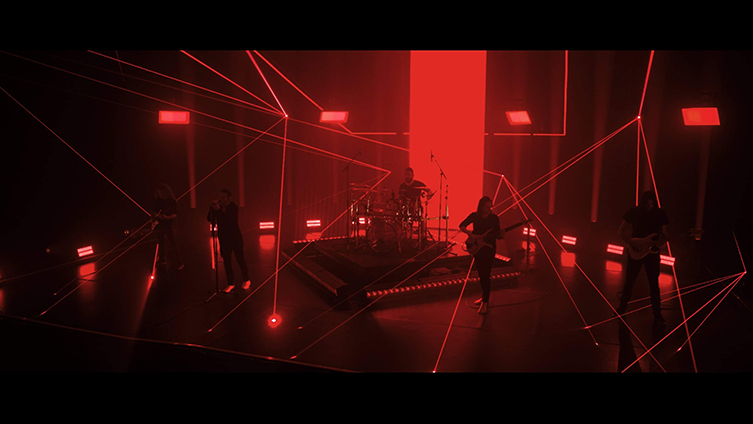

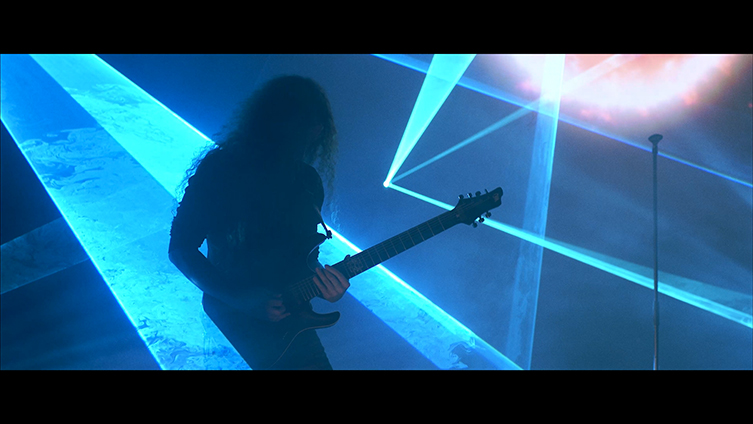

This month sees the release of Portals, a special project that in some ways is a career-retrospective live performance, and in other ways is something quite separate. Portals, filmed live (though without an audience thanks to Covid), combines a superlative near-two-hour performance from the band, interspersed with scripted cinematic narrative scenes to provide artistic context and a dramatic through-line for the performance.

How many bands give us stuff like this?

One of the main creative forces behind this project was bassist Amos Williams. A multi-instrumentalist with a background in orchestral percussion, Williams was instrumental (forgive the pun) in designing not only the overall concept of the performance, but the look and style of it, too. We wanted to know more, and so headed directly for the source! We caught up with Amos recently via Zoom, and enjoyed a thoroughly in-depth chat that took in Fine Art, Blade Runner 2049, playing with audience expectations, the notion of leaving hints and cues in music, and tons more! We cover bass playing techniques, inspirational figures and the benefits of a backline-free live setup! Amos is knowledgeable in many areas, and eloquent at expressing his points of view. Our conversation was very enjoyable, as we hope you’ll find in the full transcription below.

Amos Williams Interview

Guitarguitar: So, today we are talking about Portals! I wanted to talk to you in particular because I was told that, of all of the band members, you were the one most involved with the concept and the cinematics. Why don’t we begin there? Portals isn’t just a performance: there’s more to it, isn’t there?

Amos Williams: Yeah, so I’ve always been the member of the band that’s focussed on live production. I’ve had a bit of a background in stage tech’ing when I was younger, and also I’ve always made friends with the production crew and got really into what they’re doing. Art is also really important to me. I have been the fundamental drive behind the design for all of our output, you know, designing logos and stuff like that. So, it kind of felt natural for me to run with the ideas I was having because we were in the situation of being able to do a show without restrictions. Having that history of exploration and experimentation when it came to talking with people that we might work with, not just on the visual production side but also the film and also the video content creators as well, so it made sense for me to just run with the idea that I had with Portals. It seemed to really pull everybody together and that, to me, is the mark of a successful project: when the whole team is infused, the whole team is energetic and puts their utmost into it. It’s kind of what made me really happy about the show: it wasn’t just finishing the thing, it was the fact the everybody involved really seemed to be 100% behind the idea and not just filling their role but actually going above and beyond in every sense of the word.

GG: Fantastic! I wondered if we could talk about the concept behind the cinematics? I don’t want you to have to spoil anything for those who’ve yet to see it, but from what I gather there’s a male character who goes from being a child to an adult, and a female who’s like Gaia. There’s a monolith element to it, too. Are you up for talking about that stuff at all?

AW: Yeah! I mean, the thing is, interpretation is wonderful and I’m always fascinated by how people react to things and what it stirs inside them. I really love to hear people’s take on the things that we do, even though I know my take! See the thing is, I’ve only got that perspective. Perhaps I’ve missed details that are clearly there (laughs)! Which is strange, because you think, well, they can’t be there because you made it and if you don’t know it...not true! If other people read into it, then it means that from another perspective: that’s what’s there. Often I think the weird and the wonderful arise from people’s perspectives. That’s the beauty of working in an ensemble since it’s more than one person’s vision, and you always find things that you wouldn’t expect, that are obvious to those people but hidden to you.

"Flea was almost playing drums on the bass, quite often. It's something I feel has shaped my approach to bass guitar."

In terms of what we put into the show, it’s really quite simple. The story doesn’t say anything deep or meaningful or metaphysical in any sense, but what it does is it completes a story arc which is essentially the first chapter of Tesseract. We started way back in 2010 with an art piece that was in the first EP we released, which was called The Long Journey. Now, not many people will know about this because there weren’t that many physical copies put out, but that kicked off the journey of a small boy, and this is the small boy you see in the acts III, IV and V of Portals. Now, we see the end of the journey at the end of the booklet of Sonder, which was our last album. I wanted to find a way to expand upon that but also show what went on before, because I’m very keen on the non-linear way that stories work, mainly because I have epilepsy and the type that I have does a weird thing to the concept of time sometimes. When you try to explain what you’re experiencing, people look at you as if you’re just fucking mad (laughs), which is, I mean...whatever! Maybe! (laughs) But then a neurologist will explain what’s happening to you, and I just wanted to explore that, because we’d done this and we’ve gone through this ten year journey, so I wanted to find a way to show the bit before.

This is something that’s inspired by the story: it’s not like the story came from the prequel. So, you have Gaia, the female character, who essentially looks at what she’s experiencing and wants to understand. It’s just a simple case of looking at something and not being able to fully comprehend it. Obviously there are connotations there because she is this being, alone in a void. There’s this doorway, or portal, or energy and she decides to step through it.

This is where the creative story comes into it; where the concept of what it’s like to be somebody creative, writing, painting...there’s this moment of frustration when you hit the first step of your journey, where you don’t understand where you’re going, perhaps. This is where Act II comes into it, and where it speaks about all and everything at once, because you suddenly see the possibilities: a fear, a frustration and an anger can well up in you sometimes that’s too much to take. That was what led us to the concept of using white as the colour for that section, because it is everything: you can’t discern shadows or tones. There’s no gradient, and this is represented rather crudely by Gaia trying to talk to us, breaking whatever the 4th wall might be. She’s talking directly to the camera, but we can’t hear her. It was just a way of trying to bring the frustration in. We added some subtitles to that because otherwise there would be some people thinking something was wrong and we just wanna make sure that it was not the case!

So, the idea is then that she sends this element of her off into the world, which is the small boy, just to get some perspective, some understanding from a different point of view. Again this is about the creative story: about what happens to a writer, what happens to a musician. Often, like I was talking about much earlier, you don’t know what you’re doing! (laughs) Often you really need somebody else to say, well, this is what’s happening from my perspective because it changes your reference point. So, you see, it’s actually a very simple story, but the analogy is somewhat mysterious because I think it would be a shame to have dispelled and popped that sphere of mysticism and pseudoscience/pseudo-spiritual element that seems to arise within TesseracT’s music.

So those are the two characters, and the portal allows you to traverse between these snapshots of their journey. As a result as well, between snapshots of our journey: between albums, who we were at different points of our career...so it’s kind of a retrospective. And then we balance that with a retrospective story, in a sense.

GG: Yeah. Some of your listeners might enjoy the clarity of you telling them this, because it helps support their own point of view, even if they would’ve come to the same conclusions themselves.

AW: True!

GG: It’s like you said earlier: sometimes, on your creative journeys, you could already be on the right path, but it is helpful to have someone say, ‘you’re on the right path!’

AW: Yeah, they might be a kilometre down the road, saying ‘Hey, dude, there’s a tiger down there!’

GG: Haha, exactly! Now, you touched on some very interesting things that I’d like to go back to, if that’s okay?

AW: Please.

GG: One of them was, you referred to non-linearity. I think that is probably one of the best descriptions of TesseracT’s music. Obviously, calling music non-linear is a kind of strange one because it has to be sequential – you have to listen to it starting at the start and ending at the end, as it were – but it seems to be that TesseracT has always had a non-standard attitude towards song structure and time signatures. Do you reckon ‘non-linearity’ is a fair shout?

AW: One of the more explicit examples of the concept of the way that I look at nonlinear responses are when we master an album, the order of songs is very much dependent upon what came before and what’s coming after. That’s most apparent on our first and second albums actually, where this was a big thing for me, I pushed really hard for these things to happen. It seems to be very key to give yourself a lynchpin. The beginning of an album might not be the most grabbing song or anything like that, but it does set you on a path that does allow the songs to have more emotional impact. It’s all gearing towards the way the end of the album leaves you. But that’s obviously looking at it like you’re listening to the whole thing as one.

When we were young, we were keen to, like, create a 60 minute song, that sort of vibe. We’ve now relaxed on that somewhat! I don’t know that it’s fair to ask people in this day and age to ask people to commit their time to you, because there’s so much going on, so we’re not so much fussed about that any more. We’re not going to say, ‘this is an album that only works if you listen from start to finish’. Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon is a bit like that: there’s a story there.

GG: Sure.

AW: Actually, to use Pink Floyd again, listening to Shine On You Crazy Diamond broken up just doesn’t work! Breaking that up is obviously heresy, don’t do that! But then it’s the idea that what comes after has as much impact on you as what’s happening now and then vice versa. I think your memory of the music is fascinating. You almost have an anticipation, and if you are aware of that anticipation as a musician, you can try to maybe remove things, or build things into the song that make the impact a bit better. You’re always thinking about where you’re going versus where you’ve come from. So, it’s fascinating to see when that works for the audience, when their memory of where a song is going then: they know what’s coming next but they also feel it more because you’re trying to allow that to happen.

"I'm thinking, 'sounds great!' and then all of a sudden I'm hearing a Mariah Carey song coming through my amp!"

GG: Right, let’s take that a little further, Amos. This is really interesting! I don’t think I’ve had this conversation with anyone before, about how...you’re absolutely right, because you’re setting up a something: with the first three tracks, you’re setting up an accumulation of, for want of a better word, data. Or Experiences, or whatever the listener’s getting. What I’ve never considered, and what you’ve kind of said to me, is that you can then, as a musician, make the decision of whether you want to then reinforce the expectation, or remove or subvert it.

AW: It’s very much like a film.

GG: Yes! Exactly.

AW: And in my mind, because it’s a temporal artform, it’s pretty much the same. There are actually some painters that, if you can allow your imagination to look at something in a way that’s almost beyond the static nature, you can see movement. Like, there’s a French painter called Cezanne, and I don’t understand quite how, whether it’s my imagination, but his way of painting adds movement to a still image. I think it’s wonderful to then just experiment to the point where you get that with music. With film, I think it’s easier because there are visual calling cards that can be placed around that subtly tell you about something happening.

This is where classical music beats the crap out of a lot of modern contemporary music, because they will let you know something’s about to happen, or they will do it minutes before. Chopin does some amazing things: he’ll change key (clicks fingers) like that and you’ll go ‘why is that okay?’, because it’s an awkward change. It’s because he was repeatedly playing that note, but it was three or four minutes back. It’s just utilising those tricks, and more often than not, rhythmic tricks are the ones that sneak through without people realising. I love little things like that! The annoying thing is, we often don’t realise that we may have done this until, say, we’re on tour and we go. ‘alright, that’s happening here.’

I think Smile is a good example of that. That was just a song from Sonder where there’s something about the repetitive beat that’s on the drum stack that’s just literally (taps out beat with fingers) and on its own, that doesn’t really work as a backbeat. But then it’s leaning into the much, much heavier chorus that comes after that. It allows you to hear this change, and these two lines going against each other. It’s not difficult to listen to any more because you’ve had this jagged separation going on all the time between the backbeat and this constantly-moving-forward pulse against it.

I find that’s the beauty of being in something like TesseracT. You can experiment and almost play games with music.

GG: Yeah, most definitely! Now Amos, this is great: every time you answer a question, you give me more stuff to talk about, which is fantastic! (Amos laughs) I have my little list of reference points and, you know, we’ll get to them if we get to them, but you mentioned Cezanne and I wondered: I guess you’re referring to his brushstroke technique. What I was thinking, before you read my mind, took my thought out of my brain and said it for me was: ‘space’. We were talking about temporality within music.

AW: Yes.

"Learning TesseracT has had a very strange effect upon all of us."

GG: And how with film, you can cue people. I immediately think of a McGuffin in a Hitchcock film or something, like, you place the gun in the first act, it must be used by the third act, that kind of visual language that we all subconsciously pick up on. I was thinking of TesseracT and your music: although you were saying that at the beginning you guys wanted the big long statement, the whole album experience, and maybe you don’t feel that way now, I thought to myself as you said that: certainly that’s the case, but you guys are very clever at using space to kind of still position the listener. I don’t know if I’m articulating that as well as I want to...

AW: I understand where you’re coming from. This was really important in the set design for Portals. The use of negative space as a character. This is a prime influence on the mix that we’ve always had. We always need to give you a space in which the music happens and we need to do that as well with the set design, particularly with Portals. There needed to be negative space because it was all about building these structures and shapes and you could only do that with this endless void that could come and go depending on what’s in front of you. They just wouldn’t have the power that they did have if it wasn’t for that.

It’s a shame that we didn’t have slightly more time, because I wanted to invert that. I wanted to make the whole thing white, but the setup for that was kind of nuts (laughs), I wanted to do both. I wanted act II to be the white act.

We have musicians like Victor Wooten: in his book The Music Lesson, he talks about the man that steps up and doesn’t play the first note of the beat for his solo will be the man that everybody pays attention to. I’m paraphrasing him but it makes sense. It’s because there’s suddenly a pocket for the audience to jump into, to give them a space to pour their concentration into and I think negative space allows for that. I think it can exist in art and film. A prime example of that in my mind would be Blade Runner 2049 by Denis Villeneuve. The way he positions most of his actors, they are pretty much puncturing a lot of space: there’s an awful lot of space in each frame but that allows you to exist in that frame because you’re not looking all over the place. Then look at Star Wars, the prequels, there was something in every pixel and I couldn’t watch it in the end.

GG: Yeah!

AW: It’s just about shaking hands with your audience in the end and inviting them in to sit around your table, rather than saying, ‘No, you stay over there and watch what I’m doing’. Particularly with vocals, I think it’s very powerful when there’s an element of surprise that you’re not there. We’ve all got these contemporary expectations: we’ll find that there are melodies that fit and conform, and rhythms that fit and conform. An example is particularly the backbeat in Western culture. If you mess around with that slightly, not only are you grabbing attention, but if you do that and give people enough room to appreciate it, then I think it draws people in. I think it shares what you’re doing, rather than shows what you’re doing.

GG: That’s a great distinction! There’s so much to go back to with this conversation! It’s great! I think you bringing up Blade Runner 2049 is quite an interesting one because you’re quite right, um, it would be Roger Deakins the cinematographer that would have probably created a lot of his shots, and I think he tends to use the Golden Ratio to compose his shots. That leads me towards other things I wanted to ask about, like the use of a monolith image but also more generally, and I hope I’m not being too obvious, but your band name is TesseracT, which is related to Platonic Solids and to Sacred Geometry and so on. Is all of that relative to the creative aims of the band?

"It's about shaking hands with your audience and inviting them in to sit around your table, rather than saying 'No, you stay over there and watch what I'm doing.'"

AW: It definitely is a muse and an inspiration, but we learned quite early on not to adhere to these things. I think putting yourself in a corner can limit your options. They can certainly give you a good direction! But yes, we will always use concepts to do with geometry and particularly things like popular science and culture. We definitely started off like that, and you can see us now growing away from that.

The core of these are still there, so for example Sonder still very much has that at mind, the metaphysical concepts of living outside your own perception and experiences. We then moved that on to things like Empathy and Humanity by saying ‘you might experience a very full life, but you must appreciate that the person that you accidentally brushed also has a life as wonderful and full and rich and terrible in some instances as yours’. We’re not saying anything with these things! (laughs) That’s the thing that always makes me worry when we explain! I always worry that people might get a bit annoyed that there’s no deep meaning to anything we do, there are just interesting muses, interesting thoughts that we seem to be able to apply to our art. That’s all you can really do with art. If you set out to change the world with it, I think you’ll always be disappointed because you will always fail. There are some geniuses amongst us that are sharp, and do manage to cut through the crap of life but we’re never gonna put ourselves under pressure to create something like that. If it happens, great. But if not, we’ve still gone through the journey and the process of creating something which we enjoy, and like I was saying at the beginning, (laughs) somebody else will see something in what you do that might be far better than what you see, so it’s interesting to not force yourself into a mould for an idea. It doesn’t necessarily give other people the freedom to see things in your idea too. I think that’s what I love in Impressionism and Symbolism, things like Klimt and that. It’s just wonderful to read into it what you may, it’s exciting.

GG: Yeah, the idea or word that I keep wanting to come back to is ‘space’, because you’re allowing the listener their own space to fill in that certain percentage that’s left. TesseracT are often quite a complicated sounding band and frequently there are parts that are quite busy and involved. That is, of course, a big pay-off for the listener, but you are not just doing that. One of my favourite bands is Meshuggah, and they are relentless: it’s an hour of intensity! So, space comes back and I think that’s a really important part of your sound.

AW: Obviously, the reason why TesseracT exist is because of a shared love of Meshuggah! Both myself and Jay the drummer, that was how we made a connection with Acle (TesseracT guitarist), because we were in different bands at the time. We shared the stage with Acle’s previous band, Fell Silent, a wonderful band that went on to produce TesseracT and a band called Monuments. The influence of Meshuggah is so subtle and it gets right into you, it changes everything for you! (laughs) It’s weird, it’s like a codex to something else!

GG: It is! (laughs) It totally is!

AW: They are so chilled out and cool, you just wonder where it all comes from when you’re lucky enough to spend some time with them. Such a weird thing, but even though Meshuggah are relentless, I think it was necessary for them to be that.

GG: Oh, entirely!

AW: We needed an unrepentant form of metal that just knocked the door down of the stale air that existed in rock and metal come, when was it? I think it was the late 80s they started up?

GG: Yeah.

AW: And for them to have anything like what they were doing in the middle of hair metal days is just crazy. They started out sounding like Metallica, but where they ended up was not Metallica at all.

GG: Yes, within about 7 years, with the Destroy Erase Improve record, that’s when it really happened. Not that I want to turn this into a piece about Meshuggah! I should reiterate that they are phenomenal, but I do enjoy the dynamic change and respite that TesseracT allows. Your brain is filling in the rest of the picture, and I wonder whether than means that when you guys have an extremely dynamic moment, and then you don’t, that dynamic difference gives the listener time to sort of feed on that, if you like? Digest it before the next one comes?

AW: I think it’s easier to understand a moving picture at a slower speed (laughs), or you know, it’s easier to get things when it’s not just beating you down. But, that’s just our approach to it. Perhaps Meshuggah’s desire is to bludgeon you with their relentless machinery?

GG: Yeah, it’s thrilling, and it’s necessary that they do that because, as you said, we needed that to happen.

AW: As I say, TesseracT exists because of their violence, haha! But they are something else but I am grateful for that.

GG: Aren’t we all! Now, talking about complicated music, lots of parts within TesseracT’s oeuvre are non-standard, and that’s obviously the appeal. I wondered, talking from player to player: do you A) have to keep practising a lot, and B) when you come to the time signatures, do they come quite naturally for you or do you still have to count when you’re playing?

AW: Interesting thing about the time signatures that we’ll move onto just after I approach the discussion about being a player. Learning TesseracT has had a very strange effect upon all of us. It’s something that we are all individually going to address over the next year or so. It’s almost had a detrimental effect on us as players because of the nuances and details, which are almost as important as the obvious elements of Tesseract. Your brain changes a bit; you find yourself just not thinking about notes, not thinking about chord shapes, not thinking about the standard things that you would be thinking about as you were approaching, say, a fretboard. Especially when the tuning – and it may be the tuning that has done this, the slightly weird, non-standard approach to DADGAD tuning and the other dropped tunings that we have – it means that you’re thinking song by song, and you’re almost forgetting the harmony behind it.

"The man that steps up and doesn't play the first note of the beat for his solo will be the man that everybody pays attention to."

Some people would say that’s great, you’re free from western harmony, and to others, I think they would agree with me: it’s actually quite hard to then play other music (laughs) because you just find yourself going, ‘I don’t know what I’m doing! This instrument is alien to me, now that I’m not playing TesseracT on it!’

I’m definitely gonna spend a lot of time this year rediscovering standard tuning and things like that. Playing the instrument in the way it was designed to be played instead of in TesseracT fashion, which is in a weird tuning where you need to get custom gauges of strings and things like that because it’s all just a bit odd!

I think it’s much easier for the drummer to remain a part of the rest of the musical world, and certainly for Dan the vocalist, than it is for us stringed instrument performers. Mmm, so sorry, the second part of the question was? I’ve completely forgotten!

GG: Haha! Not at all, that was a very good answer, so it was worth it haha! It was about time signatures, whether you have to remain focussed and so on.

AW: Um, I’ve been ridiculed for my reply to this question, which is: it’s all in one! It’s very hard to count anything that has – particularly the polyrhythmic elements and the syncopated elements of Tesseract – because a lot of TesseracT is written in a really quite dumb fashion! So, you’ll have a beat, and then if you use the triplet accent faster, so say you were in 120 bpm and you find the semiquavers are accenting every third semiquaver, it gives you a metronome that makes that beat sound groovy. It’s written in that fashion, and then you find all of a sudden that it sits in more than one time signature, it has very strong roots and connections to more than one. This is something that we did on the first two albums a lot, because we were trying to do a lot of quick changes where it would be quite easy to switch between time signatures because you already set up that time signature by accenting the relationship between the two.

You’ll find that a lot of what Acle’s doing is, he realises that unfortunately it means that the metronome is now something like 121.4 because he’s had it at 180 but it’s like 3-4 over another time signature completely. This means that it almost doesn’t matter! You just need the ‘one’ (clicks fingers to explain a series of ‘ones’). I kinda like that but at the same time it’s really disappointing for people to find out that we’re not masters of the metrics!

GG: It’s also quite helpful!

AW: Metres are often unimportant but obviously you do come to the point where you need to talk to each other and you need to discuss an idea. That’s when theory is very important, but none of us are masters at this, to our detriment, I think. I think we would be far better, but then maybe we’d sound more like somebody like Dream Theater if we completely knew what the hell we were doing all the time. They are great at what they do, but it is of their time rather than of our time. I’m gonna say that without technology, we wouldn’t exist, as well.

GG: Okay.

AW: Just the simple ability to be able to experiment with time signatures and with polyrhythms and syncopated metres means that it’s easy for us to do these things. We don’t have to conceptualise it before creating it, which (laughs) almost means that we are in the dark, and deaf and blind and we stumbled upon these things! There are times where I think the accident is far crazier than any concept could be, simply because, again, you’d have to be some form of savant to really get the concept from an intellectual point of view instead of from an explorative point of view.

GG: I think you’re being very humble, by the way.

AW: Haha, no, no, it’s true!

GG: Well, you can say it’s true and I can say you’re very humble! I don’t think you can play TesseracT’s music without being an extremely good musician, but that can be my opinion! (laughs)

AW: I think everybody in TesseracT is great at performing TesseracT and that’s what I think it’s got to, which is why all of us are going to spend some time doing more than just that. I do think it’s detrimental to your music health to only do the one thing, and especially when the one thing is so non-standard, perhaps it takes you away from the rehearsed ability to do other things.

GG: Yes!

AW: I grew up performing percussion in orchestras, and I find it weird that I’m now not doing loads of different music, because for a good ten years I’ve been focussing solely on TesseracT. Maybe I’m just looking at it from the point of view of friends who are geniuses and they are just incredible musicians: people like Plini and people like that, people who could pick up their guitar and probably play anything they wanted that day. Whereas sometimes I pick up a guitar and I don’t know what it is! Unless there’s a click track going on or something like that, you know?! (laughs) I’d be screwed if I was busking! I wouldn’t be able to do it!

GG: Haha, yeah but the other side of that coin is you don’t get many buskers that are able to play TesseracT songs. And that was one of the things I was thinking: you can find a great many bands that will do your Bob Dylan cover and your Led Zeppelin cover, but not so many can cover the types of songs that TesseracT writes.

AW: Yeah, we’ve become specialists!

GG: Indeed! Now, why don’t we talk basses?

AW: Cool!

GG: So, we’ve mentioned Pink Floyd and Meshuggah, but who were your most influential bassists when you were learning?

AW: When I was very young, it would be people like Flea from the Red Hot Chili Peppers. I found his personality so attractive . You could listen to a song, and he had an audio character, and I just found it great. I was coming from classical percussion. Western percussion but also Eastern percussion, I studied Gamelan for 5 or 6 years, which is an Indonesian percussion instrument.

GG: I know it from the Akira soundtrack.

AW: I have no idea why I was doing that: it was just something I did as a kid, but it’s had a strong influence on my ability to accept different harmonic foundations and things like that, because nothing was tuned, nothing was tempered. It was all tuned to itself, which is brilliant! I loved that concept! So I’d gone from that, and I’d always wanted to have a connection between rhythm and melody that was very strong. When I was playing the drums, I’d conceptualise it as a melody rather than ‘this is a tom, this is a hat’.

To get back to Flea, he was almost playing drums on the bass, quite often. It’s something that I feel has shaped my approach to bass guitar. I do feel that I use quite a lot of percussive elements, and I feel that they are almost more important than everything else to what I’m doing. I don’t necessarily hear the harmony behind the bass: I hear what I’m doing to the track. I could probably do things that seem a bit weird, like, certainly some things that might annoy some drummers, because I’ll be reinforcing what they’re doing, or filling a big hole that they’ve left that I feel needs filling.

I think he definitely had a massive influence on me, and it has developed into people like Marcus Miller with his double thumb technique. I mean, he’s a wonderful musician, and not just from a bass point of view: from an everything point of view. I love listening to the ensembles he works with. There’s nobody groovier or funkier out there than Marcus Miller, in my opinion.

But there’s an approach taken by Victor Wooten, and he’s phenomenally talented, but he doesn’t seem to care. Now, I know that’s not true (laughs) but it’s his aura: he’s just enjoying the moments and if something slides slightly off, it’s alright. Something doesn’t sound great? It’s alright, because he’s already doing the next thing that’s incredible. I dream to be that supremely free and that supremely free from seemingly conscious thought, which I think is beautiful.

So, I’ve gone from Flea to Marcus Miller and into Victor Wooten and yeah, these approaches to the instrument all have one thing in common, which is character and a personality that shines, regardless of who they’re working with or what they’re doing. And they don’t have to be doing anything complicated. I think I’ve always wanted to emulate that. Certainly on our first few albums, I had a desire to prove who I was, that was really shining through in where I’d push adding some complexities and things like that. Maybe now I’d look at it and say, ‘Ah, you’re showing off a bit, you don’t need to do that’, but I think me doing that had an influence on the rest of the band. They’ve added slightly more unusual elements: Acle now does a lot of percussive stuff that he certainly didn’t do at the start and I think it was because, by playing with me in unison, he found it quite fun. And that’s the key thing to everything Acle writes; it has to be lots of fun. It has to be something that, once it’s under your fingers, it’s just cool to play! Fortunately, it’s cool to appreciate for the audience as well.

GG: Brilliant answer! I’m having such a good time talking to you. So what about the basses themselves? What are your favourite types of basses to play?

AW: I’ve always been keen on the Music Man style: pickups and basses, that sort of big, noisy, open sound that’s just got a lot of high gain. I think my signal chain has always had high gain in it, because I’ve always wanted to include things like left-hand muting and tiny percussive elements that have far quicker transients. So, I’ve always gone for quite an unusual tone for bass, that’s got a lot of capacity for the high end. A lot of air, a lot of clicks and clacks can be heard, which is not always a great thing. I once had a rig that had a couple of valves in a compressor and that’s fine in Europe, but as soon as you go to America and they have different analog radio systems still knocking around, you would pick noise up and interference. You have the big Music Man stuff with valve compressors and unshielded circuits (laughs) and I’m thinking, ‘Sounds great!” and then all of a sudden I’m hearing a Mariah Carey song coming through my amp!

"That's the beauty of being in something like TesseracT. You can experiment and almost play games with music."

I’ve always loved that sound, and that must come from Flea, that sort of punky vibe that he then matched with a funky vibe from the late 80s- early 90s. I’m kind of moving in a more dark wood tone situation where I used to have quite a flat bass setting, around about zero on the preamp. I’ve now started moving to a Walnut body vibe with Panga wood and if my knowledge is correct, it’s connected to things like Mahogany and Wenge, so it’s not of the same family as Wenge but it has the same sort of character. I used to have some Warwicks when I was younger that had that sort of vibe, and it was really cool because they weren’t muddy! They seemed to have these strong dynamics and that is what I want from my tone.

This has led me down to changing my flat setting on my bass to now actually really pushing the bass up and using that to drive the input, so I don’t use so much gain any more, which is intriguing. I’m going for a bigger, slower transient, but I’m also matching this with a piezo pickup in all of my basses, so I have a bit of a compressed top end from the piezo, and then I’m driving the preamp with just...maybe it won’t be all the way up on the bottom end, but it will be pretty much there. Then that will just be tweaked, depending on how the preamp reacts to that. I’m not sure why I’m going in that direction at the moment, I think I just like the big warm sound. It could be because we’re playing slower stuff, so I feel that it adds a fuller transient, particularly because we all play DI as well, so we don’t use cabinets on stage. I don’t have that weight from pushing air from a massive cab.

Without a doubt, I still need that shelf above, way above useful musical information, so everything from, like 4k up normally isn’t too helpful with the bass guitar but I definitely need it to just catch a character that seems to be up there for me. It seems to help me cut through and retain a character in the mix, particularly live.

GG: That’s really interesting about the extra-high frequencies and also, it leads me into my next question, which was going to be: I saw no backline during the Portals performance. So that’s not just yourself but the guitarists as well?

AW: Yeah. I did kind of put my influence on that from a long way back. It was about, again, creating space on the stage because I really disliked seeing mismatched cabinets all over the place. It distracted from the energy the band were putting out. It felt like you were walking into somebody’s room rather than a theatre. I don’t mean to be reductive towards everyday gigs: they’re great. For TesseracT, we want to do something that could easily be theatre. I mean, that’s where we’re headed anyway and that’s much easier for us to keep consistent. That sort of sound and that sort of tone without cabs. Things like the Fractal Axe FX or the new Neural Quad Cortex is great to play with, and we’ve just basically, almost since day one, we’ve been on that sort of tip. We’ve used sequencers ever since day one, and we’ve been able to MIDI control everything. As we get more and more connected through the sequencer that involves video and lasers and lights - albeit run off timecode and things like that – it just seems very natural for us to fully embrace that system.

GG: Yeah, it suits the sound as well. You aren’t like retro Southern rockers or anything, so having cutting edge tones makes sense. Now, I did want to ask about your technique, because I noticed you tend to use your thumb more than anything?

AW: Yeah, I think it’s because I really enjoy being quite – again, I think this stems from being a percussionist during my formative years – I kind of like the impact. It feels like some form of response to the music. I just feel that I get more of that from the thumb, and from using it both ways as well, than I do from plectrum. I find the plectrum quite hard to get any recoil, I don’t get the response that I desire. With fingers, I’m just a bit slower, and I broke this knuckle when I was younger and it’s just never really moved in a fashion that I’ve wanted it to ever since! I’m not saying I was a thrash triple finger master but it would be nice to be able to play, like 16ths at a certain speed and I just cannot do that with these three.

So, I do it with my thumb. The body seems to move better that way, so it’s more natural for me and it doesn’t seem to cause me any pain in my arm. I know other people have pain, and I’m not sure, maybe it’s because I play so hard? I reckon if I were to go and have a lesson, the teacher would probably go, ‘Pffft, chill out man! (laughs) What did the bass do to you?’ It’s probably that, but again, as a percussionist, I was hands-on and that’s my reality: that’s what I need. I need to hit something!

GG: Haha, certainly! So, does that mean that for faster passages, you’re playing up and down with the thumb? What about when you need to skip strings a lot?

AW: I don’t do too much popping at all, it’s mainly double thumb, but I still will use a plectrum if I need to. There are some things where it just...but it tends to be more for tone, you do get a slightly sharper leading edge, the shape of the wave with a plectrum. The attack of the plectrum is still gonna have more amplitude than with your thumb, unless you’re managing to catch with your nail. But even then, the area you’re catching with the pad of the thumb tends to be a more rounded tone. Again, because we are using direct, that makes a difference. You can hear the attack as opposed to the slightly slower transient. There aren’t too many calls for me to skip too quickly between strings and if there are, I tend to hammer on with my left hand.

GG: Ah, cool!

AW: And also the area of thumb that connects with the string. It’s amazing the change, just by moving it an inch or two. It’s not always that obvious as to where the character of your sound is coming from in that small little section of the instrument. I find it’s very much more prominent on bass to me than it is on guitar, for example. But, it’s crazy that you could be off by a centimetre and it just doesn’t work. I found that really interesting when I was positioning pickups on a prototype bass I was working on. I had a routing that was a good 10-12cm so I could move this Music Man pickup from a contemporary modern position to a P-bass position and it was fascinating to find the difference in what is essentially a sub 2 or 3cm distance and you think, ‘Why does it do that?’ it’s something that I don’t quite understand about the harmonic structure of the string. It’s interesting that you can really have a powerful impact, not just on the position that you’re playing from that perspective but also from the position that you’re playing form the angle you hit. Because, like I say, it’s the difference between hitting the pad or hitting the nail and the pad, or even just catching it with your nail. Maybe it’s harder for me to get that with just a plectrum, so I find there’s more nuance and TesseracT is, if nothing else, it is nuance.

GG: Most definitely! What a great answer! So, just to wrap things up, just a simple, generic final question: Portals is out very soon, so what are TesseracT’s plans for the rest of the year?

AW: Well, Portals opened up a new avenue for us, so we’re gonna be working on something that’s similar. It’s not Portals 2, but it’s more than a music show. So, we’re quite intrigued with that. We’ll see where it goes: it may not come to fruition but we’re not putting any pressure on ourselves to achieve that, which is great. We’re a band, we’re not filmmakers, so nobody expects us to do anything except be a band, which is a wonderful position to be in, creatively!

We are quite a long way into demos for our next album but we’re not forcing the time issue on that, which is great. We’re in a weird position now: everybody’s life isn’t normal, so we’re not trying to force that horse down that track at the moment. We were supposed to be touring at the end of this year, but we don’t know if that’s gonna happen. We have plans already to get out supporting somebody else during the first quarter of next year. It would have been two and a half years, I think, between our last live performance to our next live performance. Obviously, Portals was there, but there was no audience, so I am looking forward to that because that was the point of Portals, to explore the joy of performing and to celebrate that. It’s something that we haven’t done for a long time and I can’t wait to re-open that element of being a musician again! Half the fun of being a musician is sharing your music with people!

We can’t wait to see the TesseracT live experience one again, and hopefully it won’t be too long a wait! Please keep an eye on the TesseracT website for up to the minute updates, and to order your copy of Portals when it’s released on the 27th August on Kscope.

We loved how much detail Amos was willing to go into about the elements of his sound and the way his musical mind works. It was very generous of him and we hope you got lots of tips and insights. It was also a real pleasure to have such a fun, detailed and wide-ranging conversation! We thank Amos for his time and candid attitude. Thanks go also to Simon Glacken for setting us up, and as ever, thanks to you for choosing to spend some time reading with us this article! If you liked this, please head over to the guitarguitar Interviews page where you’ll find a great many more! There’s more to come too, so visit again soon!

Until then,

Ray McClelland