Our Expert Guide to Guitar Bridges

Do guitar bridges leave you a little confused? Some of them look incredibly complicated, whereas others are the definition of simplicity. How can you tell what you need, or indeed already have on your guitar?

Perhaps if somebody put together a brief blog and packed it with all of their knowledge of guitar bridges, knowledge gained from three decades of playing guitars, selling them and writing about them? Would that be helpful?

Two Gibson Les Pauls: the Custom on the left has a Bigsby tremolo.

Well, look at you, you lucky thing: that is exactly what you’ve just clicked onto! Prepare to have your senses assaulted with all of the info and facts on guitar bridges that you’re ever likely to need. I’ll cover hardtail bridge styles and tremolos, uncovering the main types and mentioning other variations that are similar to each type. Sound good? Good!

Now, why don’t we start by clearing up some of the stranger terms that surround the subject of guitar bridges…

This Charvel has a Floyd Rose tremolo system.

Contents

What’s a Whammy? And Other Questions

Stratocaster ‘Synchronised Tremolo’ Bridge

What’s a Whammy? And Other Questions

What’s a whammy bar? Indeed, what’s a ‘whammy’? Good questions, and you’re right to ask, but that doesn’t always mean that a useful answer is forthcoming. Still, let me address, in a point-by-point manner, some of the most oft-used terms, and hopefully gain some clarity on them for you…

- Tremolo: This used to refer to fast, abrupt volume changes (such as what a Tremolo pedal will still do for your sound), but since Leo Fender called his Stratocaster bridge a ‘Synchronised Tremolo’, we’ve all come to use the term ‘tremolo’ to mean a device that allows raising and dropping of a guitar’s pitch.

- Vibrato: The lowering and raising of a note’s pitch. Normally, it’s a consistent thing, as in the finger vibrato that you’d apply when playing a note on any stringed instrument, but the fact is that it means more than that. ‘Tremolo’ units on electric guitars are actually performing ‘vibrato’, not ‘tremolo’, ok? I know, I know: don’t think about this one too much. Vibrato pedals can also sound kind of like tremolo pedals, too, which doesn’t help matters. (Vibrato pedals adjust the pitch a little; tremolos ‘stutter’ the volume).

- Tremolo bar/arm: What is the correct term for the metal bit that sticks out of the bridge, which you grab and use to lower or raise the pitch of a note? Either ‘arm’ or ‘bar’ is fine, since neither makes more or less sense than the other. ‘Screw in’ and ‘push in’ merely refers to the manner in which they are attached to the bridge, since most tremolo arms/bars are removable.

- Whammy bar: This is simply another name for tremolo arm/bar. There is no difference. And no, you do not get a ‘whammy arm’.

- Whammy: what is a ‘whammy’? Good question! I’d go with it being a description of the sound, more than anything else. When you ‘dip the bar’ (the terminology for whammy bars is hilarious), the sound you make could be construed as a ‘whammy’. The Digitech Whammy pedal uses extreme real-time pitch-shifting technology to mimic this, so I feel like the sound is the ‘whammy’ more than the device. The dictionary defines ‘whammy’ as a ‘devastating blow or setback’, and another place online called it ‘supernatural bad luck’, so it’s anyone’s guess, to be honest.

- Wang Bar: A rubbish way of saying ‘whammy bar’.

- Up-bend/back-bend: The ability of a tremolo arm to raise the pitch of a note.

- Floating bridge: this can mean two very different things. One is the old style of bridge (we’ll see this in a second) that is held to the guitar by string pressure: it isn’t actually attached, hence it ‘floats’ (I know, it doesn’t make any sense). The other is when a tremolo is set to ‘float’, meaning that it can be pulled up as well as down, basically.

Okay, that seems to be most of the arcana dealt with, so why don’t I move on to each specific bridge?

Floating Bridge

The earliest type of bridge that I’ll look at today is the floating bridge. As mentioned before, it’s a simple bridge that raises the strings up away from the body, and in fact is never properly attached to anything. The pressure from the guitar strings keeps the bridge in place. Slacken the strings and you can move the bridge around, though it’s worth noting that wherever it was originally placed by the factory is really where you should leave it.

You see this type of bridge on archtop guitars, jazzers and some semi acoustic guitars, particularly Gretsches. Rule of thumb? The bridge should roughly align with the cross-stroke of the f-holes.

Notice the floating bridge on this Gretsch, with a piece of foam paper between the bridge and body.

Tune-o-matic Bridge

This is one of the most often-used bridges in the business. Invented by Gibson, the tune-o-matic bridge is superficially similar to the floating bridge we just saw, except this one is attached to the guitar via two big metal posts.

The tune-o-matic allows for some alteration of intonation, particularly in latter day versions which have definitely improved on Gibson’s simple original design. Wheels on each bridge post allow you to alter the height of the bridge and hence the height of the strings.

On the likes of a Les Paul Standard, the tune-o-matic (often written as TOM) would be paired with a ‘stop tailpiece’, which is purely functional and has no real decoration. Other guitars, particularly semi-hollow models, may have ‘trapeze’ tailpieces, which float (that word again) above the body and have more string length on show behind the bridge. This does change both the sound and the feel of the instrument, so it’s worth trying a guitar with a trapeze tailpiece to see how you like it.

A pair of Epiphones with Trapeze tailpieces.

Telecaster Bridges

The Telecaster has an entire bridge plate (sometimes called an ‘ashtray’ particularly if it has the curved bits at the sides) that holds not only the bridge itself but also the bridge pickup. Teles normally string through the body, and their bridges can have either six individual saddles - one for each string - or they can be made the vintage, historical way, where three (preferably brass) saddles each handle two strings.

A Custom Shop Telecaster with its famous 'Ashtray' bridge plate.

It all adds to that twangy-yet-strong Tele tone, you see, but some rare examples are ‘top load’ bridges. Not a reference to the embarrassing soft pop band of the 1990s but in fact a variation of the bridge where the strings slid through the metal plate from the top, behind the saddles. No through-body activity here at all, and that again changes the sound and the feel of the guitar quite dramatically. Well, it changes things a bit.

This version of the Tele bridge allows both through-body and top-loaded stringing.

Fender’s American Pro Teles currently have a bridge that can do either, and Jeff Buckley’s famous 1983 borrowed Tele was a top-loader, so fans of his wonderful sound might want to look further in that direction!

Stratocaster ‘Synchronised Tremolo’ Bridge

Most likely the first ‘whammy bar’ you got your hands on, Fender’s design for the Stratocaster was a very significant moment in the evolution of the electric guitar. It offered more scope to bend notes further (under the Mustang came along, that is) and was reasonably good at handling the guitar’s tuning.

The Stratocaster Synchronised Tremolo is the world's most popular style.

The name ‘Synchronised Tremolo’, as I mentioned earlier, is a bit of a faux pas, but we in the industry have gotten over it and so should you. This tremolo will do most of the things that most guitarists want, with its simple non-locking design. Springs that grab a metal claw in the back of the body counteract the pressure of the guitar’s strings, so when you push/pull/whatever the arm/bar, you’ll get your pitch change and then, hopefully, a return to the original pitch when you let go.

A modern 2-point Strat tremolo.

Everyone from Jeff Beck to Hendrix to Ritchie Blackmore and literally all guitar players in between have done cool things with this bridge. We often refer to them as ‘Vintage trems’ and ‘Strat trems’ too. In 1954, when the Strat was released, the bridge had 6 screws keeping it in place. Since then, an improved design that uses two screws has been created, called a ‘2-point tremolo’. Modern hardware makers such as Gotoh and Trevor Wilkinson offer upgrades in both styles.

Bigsby Tremolo

The Bigsby tremolo actually predates the Stratocaster one. It’s a big old piece of quasi-steampunk machinery that sits atop the guitar and allows a small degree of pitch changing, both up and down. Divebombs are most definitely not on the menu here, but if you like classic 50s and 60s pop, country, rockabilly and so on, you’ll probably be very familiar with what the Bigsby does do!

A Bigsby Tremolo on a Custom Shop Les Paul.

The Bigsby is all top-mounted: no chopping into the guitar is required, making this a popular bridge to retrofit. It uses one tightly coiled spring to operate, and restringing one is guaranteed to put you in a bad mood.

There’s no denying how cool they look, though, and that is often down to them being fitted to already-beautiful guitars like Gretsches. You’ll get about a tone and a half’s pitch lowering at the most, and maybe a half tone up the way, but it’s all about style with the Bigsby!

Another Bigsby, this time on a Gretsch.

Fender Offset Bridge

Fender’s offset guitars - well actually, only the Jazzmaster and Jaguar - have a very particular bridge design. The bridge itself is somewhat like a tune-o-matic, but with several ferrules in each saddle, which was and remains a mad idea. This bridge then goes to a tremolo unit that is super stylish and essential for anybody looking to make Shoegaze music, it would seem.

The mechanism itself is hidden within the guitar’s body, behind a large metal plate. The arm (I’m going with ‘arm’ for this blog, okay?) is really long and attaches to the spring-loaded element within the body. The strings themselves attach to the same plate that the long arm is attached to, and so moving the arm engages the spring under the plate that holds both the strings and the arm. Got it? Good.

The Jazzmaster's unique bridge and tremolo unit.

You’ll see these on hardly any guitars that aren’t either Jazzmasters, Jaguars or boutique builds that rip off the style of those two. The Fender Mustang has its own version, which is similar except that the bridge is incorporated into the whole tailpiece. The Mustang’s actual bridge saddle part is much more sensible than the JM/Jag’s, so lots of players modify theirs by swapping in a Mustang bridge. As for the tremolo itself, the Mustang has an almost laughably extreme amount of pitch bend on offer. Try one, especially if you haven’t considered that whammy bar!

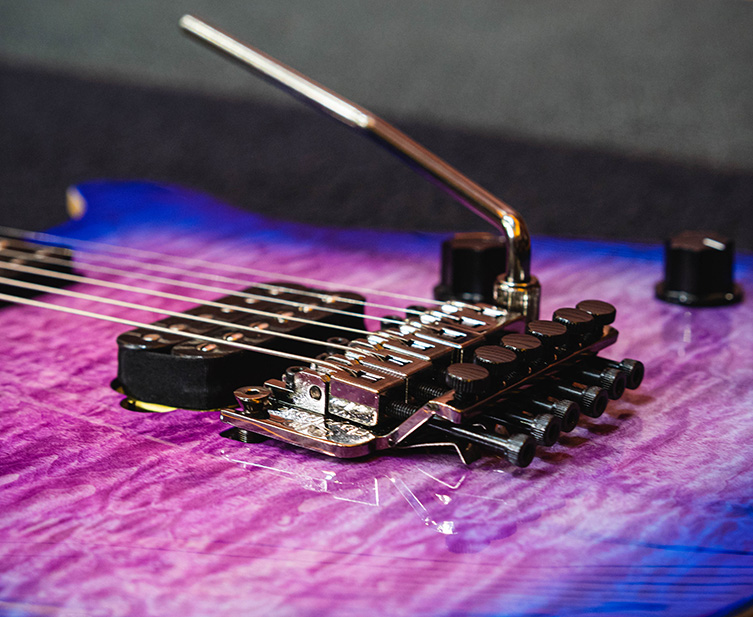

Floyd Rose Tremolo

The Floyd Rose tremolo is another one of those inventions that changed the game for everybody. Even if that meant that you didn’t like them, at least the game changed! The Floyd Rose tremolo (named after the chap who invented it) offers probably the most extreme levels of pitch changing of all of the tremolo bridges. You can literally push down on the arm until the strings go slack, hanging off the fingerboard, and then pull the bar back and everything returns perfectly to pitch.

Eddie Van Halen and Steve Vai's guitars both have locking Floyd Rose tremolos, though Ibanez make their own version, the Edge tremolo.

How does it do this? Well, the Floyd Rose tremolo locks the strings in two places: at the bridge itself (the saddles move in to ‘bite’ each string when you turn the allen key) and up at the nut, which needs to be a special Floyd Rose locking nut. Once you’ve got this all set up, though, you can enjoy a whole vocabulary of sounds, noises and effects.

The downsides are that you can no longer change tuning, since everything is locked in; and it can be a royal pain in the posterior to maintain these, particularly when you’re inexperienced. You also need to be okay with a fairly significant amount of routing being done to the guitar’s body to facilitate the system (unless it’s already on there when you buy the guitar). Still, the sonic benefits are pretty extraordinary, if you’re fine with the set-up and maintenance.

A Floyd Rose tremolo in detail.

Kahler Tremolo

You don’t see too many of these around any more, but I’m including the Kahler just in case you happen upon one. Kahler tremolos are kind of like a cross between a Floyd Rose and a Mustang tremolo, almost: you often have to lock in the strings at the nut (not all examples do that, though) and the feel and range is quite similar to the Mustang. It doesn’t operate in the same way at all, though. Kahlers are surface mounted, unlike Floyd Roses, and work with a cam, sort of like a wheel axle. The bridge has roller saddles to help with tuning stability.

This G&L Rampage has a Kahler tremolo, but it seems to be missing its arm!

You’ll see Kahlers on lots of 1980s-era guitars like BC Rich and Kramer. Some people still prefer them to Floyd Roses, but Kahler definitely lost that battle overall.

Evertune Bridge

My last bridge type today is the Evertune. It’s another gamechanger, and I’ve actually written a whole blog about it, so if you want to go further with this, please click through to my Evertune Bridges blog.

In short, though, this is a bridge that guarantees perfect tuning stability no matter what. It uses springs and levers to exert constant pressure and counter-pressure on each individual string, so that even dropping the guitar (not recommended) won’t put it out of tune.

The Evertune Bridge, on an LTD Horizon.

Here’s the crazy thing: it totally works. It’s a bit of a pig do set up, if I’m being perfectly honest, but the fact of it is that once you have it set up, you’re good indefinitely.

The Evertune needs a little routing into the body too, so do be aware of that before you start losing your sense of reason. If perfect tuning matters to you though - and if not, why not? - then the Evertune bridge is really something you have to know about.

Which Bridge is Best?

Which bridge is best? Let’s not. Best for who? If you like changing tunings for every song, a Floyd Rose is not going to work for you, unless you plan on having 15 guitars at every gig. By the same token, if restringing your guitar is already a hassle, then complicated devices like the Evertune, Floyd Rose and Kahler are going to have you seeing red pretty quickly.

I’d advise working with what you have, and forming an opinion on that. Does your gear serve your needs? If not, did anything in today’s blog switch on a lightbulb in your mind? If so, follow that path!

Also, remember that lots of variations exist out there. Ibanez’s Edge tremolos ARE Floyd Roses - they are licensed units - but Ibanez do their own thing with them. Also, PRS and Music Man make their own tremolo bridges, but these are essentially versions of the Fender synchronised tremolo design with some subtle changes.

A PRS Custom 24 with PRS' take on the classic synchronised tremolo.

Even the humble tune-o-matic has alternative takes from third parties like Tonepros. This is all good stuff, but it doesn’t mean that you need it. All tremolos are a compromise in some way - you either lose tuning stability or the ability to change tuning - but then not having a tremolo is a compromise, too, isn’t it?

In the end, follow your nose and see what appeals to you. If you feel that you are lacking something, come back to this blog and have another read: maybe the answers are right here!