The guitarguitar Interview: no-man

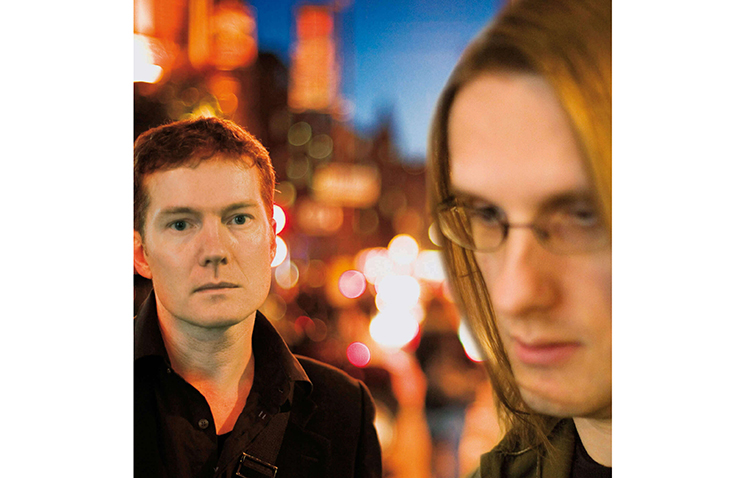

No-man is an intriguing electronic project made up by ex-Porcupine Tree frontman Steven Wilson and vocalist Tim Bowness. Since 1987, they have made a number of diverse and interesting records, each with wide stylistic differences and aims. From dreamy pop songs, through challenging Art-Rock to the duo's current electronic, synth-based sound, no-man have always found fertile ground within music that's simultaneously off-kilter and accessible.

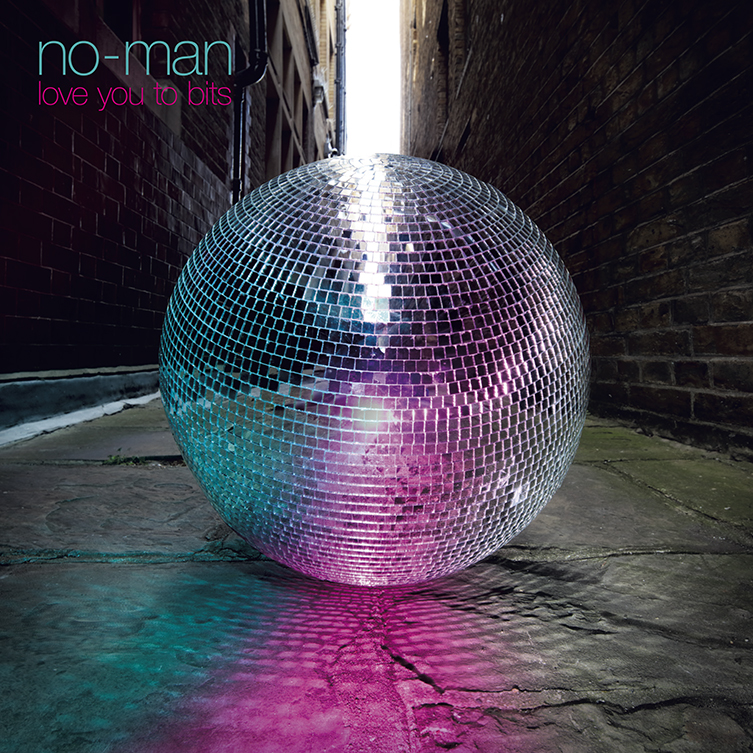

This month sees the release of 'Love You to Bits', an atmospheric recording that traces the end of a relationship. Layers of melancholic eletronic textures weave around motorik beats as Bowness' delicate, emotional vocals bring the compositions to life. It's an involving, hallucinatory record that's both familiar and quite unlike other releases this year.

We were happily able to have an interesting conversation with TIm a few weeks ago via email. His answers make for an interesitn gand illuminating read, giving both context and contrast to the music. Read on to learn more about the fascinating genesis of no-man's latest record, as well as keen insights into both the writing process and life as a label boss!

Hi Tim! It’s been 11 years since no-man’s last record, Schoolyard Ghosts. Since you and Steven have your own solo careers, does no-man just sort of suggest itself every once in a while, and come together when the time is right?

The good thing is that we only make no-man music when we want to or feel the need to. The band now is exactly as it was when we started, a labour of love.

In the case of Love You To Bits, it’s been something we’ve wanted to complete for a long time. Steven co-produced my last solo album – Flowers At The Scene – and while we were making the album the subject of no-man came up a few times.

Over the past few years, both of us have been drawn to the idea of making more dramatic, dynamic and electronic music again and at the end of last year it finally seemed the right time to make a new no-man album and finish what we’d started many years ago with the original Love You To Bits demo.

The new record, Love You to Bits, has an overall theme of ‘the aftermath of a relationship’: is this record specifically autobiographical? Could you talk about your lyrical inspiration and intention?

As in a lot of my writing, there are autobiographical elements and observations, but while containing aspects of break-ups I’ve been through it isn’t directly about any specific relationship I’ve been in.

From the very beginning, I wanted to write about a break-up from the perspectives of both of the people involved. There’s also a third perspective and that’s one that both the individuals share, but are too distant from the other to admit to. Communication breakdown!

One thing I was determined to do was include some some positive indication of why there’d been a relationship in the first place.

Most, if not all, break-up songs concentrate on the bleak aftermath, but I wanted to contrast that with moments of joy that delve into the optimistic beginnings of the relationship.

Over the last decade, I’ve shied away from writing obvious love or relationship songs and it was good to come back to the subject with a fresh energy.

Additionally, I’d been writing in the Love You To Bits lyric file for 25 years and it was nice to finally put it to rest.

In some ways, like the music, the lyrics are a fairly sophisticated and detailed account of something seemingly simple.

The record sounds beautiful! I’m getting something of a ‘future cityscape’ vibe to the overall sound: would I be on the right track there?

Thank you.

Yes, I think there is a sense of isolation in the big city in the lyrics, which is something that earlier no-man songs such as Angel Gets Caught In The Beauty Trap and Truenorth also flirted with.

In the Love You To Bits lyric file, aspects of love falling apart due to the stresses of urban living were perhaps even more explicitly addressed. Some of those lyrics ended up on a song of mine from Abandoned Dancehall Dreams.

Love You to Pieces is made up of two parts, split over ten pieces of music. Was this because certain motifs come back around now and again? It’s a very interesting way to present the music...

And one that’s absolutely perfect for vinyl!

For me the album can be seen as a single two part track with 10 lyrically and musically related component sections.

I think there is a difference tonally and emotionally between the two parts of the album. Love You To Bits is more relentlessly dynamic with moments of respite, while Love You To Pieces is darker and perhaps has more of a sense of blissful release that’s punctuated by moments of dynamic disruption.

The opening ‘Pop’ song section on Love You To Bits was originally written at the same time as a track called Lighthouse in 1994 and both songs were intended to be part of a follow-up to Flowermouth (an album we were both incredibly proud of).

Over the years, we continued to work on Love You To Bits and there were a number of demo versions which varied in length from 4 minutes to 12 minutes in length. Though we were excited by the piece it never seemed right for anything we were working on. It seemed out of place for a very long time.

As for the structure, we knew from the beginning that we wanted to do an album length exploration of the piece and we also knew that it was going to deal with the different perspectives in a break-up.

Were rhythm and groove priorities for this record?

Very.

Bruno Ellingham (known for his mixing work with Massive Attack, UNKLE and Goldfrapp) was brought in at the end of the process and his main contribution was that he pulled together the programmed rhythms and real drums more effectively.

The drumming is by Ash Soan and there’s no doubt that Ash, along with Gavin Harrison, is the most technically accomplished drummer no-man has ever worked with.

His ’simple’ grooves are surprisingly hard to achieve. Outside of that, there a few places where his playing opens out and he reveals more of his natural dexterity.

Calling this music ‘Synth Pop’ is a little simplistic but calling it ‘Art Rock’ doesn’t mean too much more. What do you tell people when they ask you what kind of band no-man is?

I stare at them silently!

I think no-man has its own sound, but even within that sound has shifted continually over the years. The same goes for my solo work and Steven’s I think.

We both have extremely eclectic tastes, though I hope in everything we do that there’s something in the harmonies, emotions and unexpected sonic and musical choices that’s recognisably no-man.

The simple answer is I’ve no idea what I’d call our music.

The record is very synthy, but there are guitars and other instruments, too. Do you guys have a clear intention of the sounds you want, or does experimentation play a part?

I’d say the music represents a combination of both approaches.

We can have very clear ideas about what we’re going after, but equally we can get carried away by experiments that lead us in entirely unanticipated directions.

Do you ever find it difficult to blend guitars with the electronics?

I think electronics and guitars often work well together. I think Pete Townshend’s early experiments with primitive sequencers and Rock band – on the Who’s Next – still sound fantastic and it’s an approach you can hear in the work of the likes of Steve Hillage, Ultravox and Tubeway Army years later, and Underworld many years after that.

In the early days of no-man we played live against backing tapes (mainly consisting of programmed/sampled beats and electronics) and the contrast between the energy and chaos of the live performances (guitar, voice and violin) and the unchanging nature of the pre-recorded parts created an interesting tension.

How does the songwriting process work between you too? Do you work on the music together in the same room at the same time?

We use any method that works. This album has been one of the most hands-on and collaborative in the band’s history.

In the very early days of the band, we worked together in real time. Wild Opera was perhaps the best example of this in that all the songs were written by the two of us while we were in a room together.

In the case of Wild Opera, we gave ourselves an hour to write, record and complete a piece of music. The starting points could be anything from guitar patterns Steven and I had pre-written to samples that we’d brought in (the more obscure the better!) to inspiring sounds.

We abandoned grooves and samples after Wild Opera and the music became more organic in terms of its texture. The majority of pieces after that point were written remotely. I may have had a complete song that I’d take to Steven or Steven may have had a finished backing track that he’d send to me to write lyrics/melodies to. After that point, we’d consult one another regarding production details, additional melodies or guest players.

From the original song to the all the variations, Love You To Bits was written while we were in the same room. Once we decided to make the album what we’d always wanted it to be, we spent three days in the studio trading ideas and putting together the framework for the finished piece.

A lot of the writing, both lyrically and musically, happened over the last year and it was a surprisingly flexible process. Ideas such as the brass band coda to Part One emerged very late on, for example. A synth tone suggested a brass instrument to me and I mentioned the idea of a brass band to Steven, who immediately liked the idea. Within the week, we had the arrangement and recording.

Do you get involved in the production side of things? If so, what kind of software, DAWS etc were you using? (I’d be really interested to know what keyboard hardware and plugins were used, if that is part of your contribution to the record!)

Yes. I have Logic Pro and GarageBand plus a Neumann microphone, PRS guitar, electric ukulele and an Arturia MiniBrute synth. Steven has considerably more! I have a few classic GForce keyboard and synth plug-ins, but I’ve not used them for quite some time.

From the start of the band, along with Steven, I’ve always suggested production ideas, overdubs, guest players etc.

Over the last decade, I’ve also tended to record and edit all my vocals in my home studio. I find I can get better results than in a studio and, generally speaking, much more quickly. That said, on occasion, I can be fairly obsessive in a way that would cost a fortune in a conventional studio. On my album Lost In The Ghost Light, a few of the vocal takes were composites of hundreds of takes. Luckily, that was an exception! Obviously, if something works within the first couple of takes, I have the sense to stick with it.

When writing music, do you tend to compose more on a guitar or keyboard? (Or something else of course!)

I often write songs by programming and manipulating sounds and rhythms and composing on the computer keyboard. I also write more conventional songs on my guitar. Of late, I’ve also written a lot on ukulele. Treated, it can sound surprisingly interesting and harp-like and it’s enabled me to break out of the chord habits I naturally gravitate to on guitar.

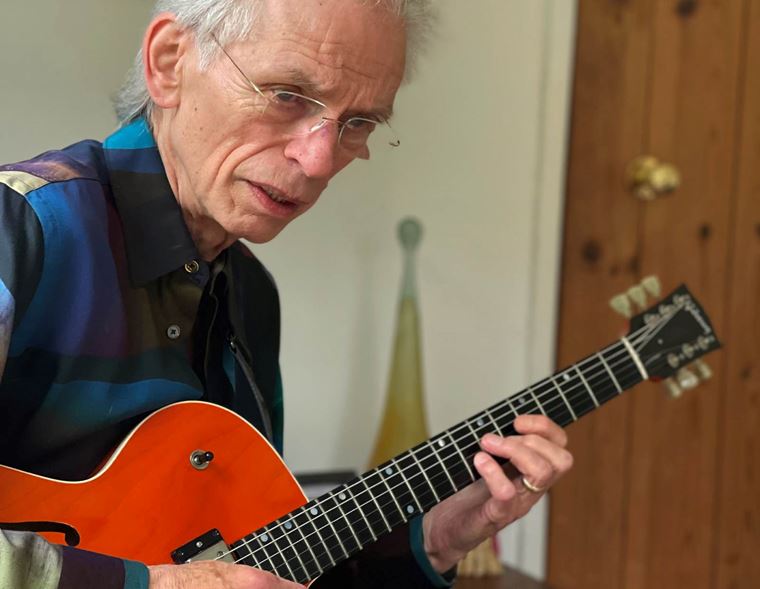

No-man records in the past have had some pretty impressive guest artists like Robert Fripp, for example. Are there any other musicians on Love You to Bits, other than you and Steven?

There are, but none as high-profile as the marvellous Mr Fripp.

We have to feel that our chosen guests can bring something unique to our music and that our music can bring something interesting out of the guests themselves. There’s never any point in having a collaborator involved for the sake of the name.

Getting Robert involved with no-man was a thrill for both of us and his contributions to Flowermouth still sound wonderful to me. It was an incredibly relaxed and enjoyable session.

Love You to Bits (Bit 4) has the most incredible atonal guitar part in it! Who played that? And how did it come about? Love You to Pieces (Part 2) also has a fantastic keyboard solo. Can you tell us about that, too?

The solos you mention are the contributions from Slovakian guitarist David Kollar and keyboardist Adam Holzman (Miles Davis etc).

Originally, Theo Travis played saxophone solos throughout a lot of the first half of the album. As good as Theo’s solos were, we didn’t feel they had the necessary bite for the track. We wanted something quite extreme from both David and Adam and in the case of both, what’s on the album are third attempts. We kept on going back to them and saying, ‘More!’

Throughout the record, some of the backing vocals are pitched down or processed with a vocoder: does this type of treatment feed into the concept of the record? Or is it just because it sounds cool?

Both, but probably cool wins out! J

Overall, I’d like to think the album contains some of my best and most versatile singing and there’s no doubt that the processing adds to the variety of vocal approaches on offer.

I really love your singing voice! Who were your vocal influences?

Thank you.

When I started, the three singers I most admired were Peter Hammill, Peter Gabriel and David Bowie. I was also a big fan of singers such Paul Buchanan, Nick Drake, Paddy McAloon, Nina Simone and Chet Baker.

Does no-man have plans to tour this record? It’s such an interesting mix of ‘proper songs’ to use a silly term, and music that would really suit a dancefloor. How do you approach performing this kind of music live?

A good question!

While not being particularly like it, the new album has more of a kinship with the music we were producing in the early 1990s than what we’ve produced over the last 25 years.

The last two tours have featured a sound more like (a surprisingly hard-hitting) Rock band with Modern Classical influences. We always try to work to the strengths of the live musicians rather than attempt to replicate the sound of our albums.

That said, if we do tour this (something which has been discussed), I anticipate a very different approach and possibly a great use of backing tapes (something we haven’t worked with for a very long time).

You are one of the founders of Burning Shed records. How difficult do record companies have it these days? And how much of a typical day does dealing with that business take up for you?

Less than it did as we now have quite a number of staff at the Shedquarters. I’m mainly responsible for selecting and finding the music that we sell and writing the site and newsletter text.

Bizarrely, despite the overall industry downturn for independents, Burning Shed has consistently grown over its 18 year history. I’m all-too aware of how fragile things are, but for now the company’s thriving (we have a database of 100,000 active customers who subscribe to our newsletter) by selling physical music media.

Overall, do you see music streaming services as a good thing or a problem to work around?

For reasons I’m happy to go into, I find streaming a little inadequate as a means of experiencing music, though I completely understand why people use and like it.

I think that if it does become the sole future for music, it would mean the fall of many independent music labels, the loss of even more music industry jobs, and the almost total disappearance of income for most musicians - especially non-mainstream artists who are already finding things tough.

What the digital companies pay for streams is pitiful and what little they pay is filtered through aggregators, collection agencies or labels.

For the major labels, who have decades of back catalogue to offer digital platforms, no physical media will mean costs are down as they no longer need product manufactured, warehouses to store the product in, staff to run the warehouses and so on. Digital marketing, data uploaders and influential playlist placement are the growth areas.

Profits from streaming are filtering through to major labels, label shareholders, digital music companies, and mobile phone and Internet providers. Whether by accident or design, corporate control is stronger than it ever was and musicians in general earn less than they ever did. This doesn’t take into consideration engineers, producers and music studios, which also face massive pressure from home studios and reduced recording budgets. The diminishing number of audio experts are also being devalued in this environment.

I also feel that streaming is destroying good listening habits, and partly as a result of that, negatively impacting on the nature of music creation itself. The format is immediate, disposable and, above all, convenient. The appeal is obvious, but evidence suggests that the average listener has become more like an A&R person and gives a song only a few seconds to impress them.

When you invest in a physical album or single, you tend to give it time. I personally enjoy the immersive ritual of losing myself in music while poring over the credits and artwork on gatefold LP or digipak CD, and I find that if I don’t immediately like something, I’ll give it a few more chances due to that investment. Some of my favourite music I initially hated and even if I continued to hate something, I found I’d learned something about my tastes on the repeat listens. For some people it will be different of course, but in general I don't think streaming encourages deep listening.

Fans don’t owe musicians a living, but I think the realities of what the digital era is doing to music should be discussed more openly. Most listeners don’t care how the music they like is made and what it costs to make it, and why would they?

A simple question to ask is: is it right that streaming platforms and mobile phone companies do better out of music streams than musicians themselves? It’s as if in the age of vinyl, the manufacturing plants and plastic companies were making a fortune while the musicians busked on the streets for pennies.

I’ll stop here, but needless to say I think it would be a great shame if physical music media disappeared altogether and I believe the ramifications of a streaming-only future based on the current business models will mark the end of many careers, strengthen corporate influence, and mean less interesting and less diverse music being made.

We think Tim had some very interesting points to make there about the current state of music in terms od distributiona nd consumption. As a label owner, he is putting his money where his mouth is, and as an artist, he is contributing to the tapestry of new music that needs to occur. His new work with no-man is a detailed, emotive and involving listen, as perfect through headphones during inter-city travel as it is on a dancefloor. It's a great listen and deserves repeated plays!

Check out what Tim and Steven are up to via the no-man website. I Love You to Bits is released on 22nd November. We'd like to thank TIm for his excellent participation and to Abi Skrypec for setting us up!

Until next time.