The guitarguitar Interview: Steve Hackett (July 2020)

It’s still quite an incredible thing to listen to those early Genesis records.

When you put on something like ‘Selling England by the Pound’, you have to picture the people who created it: 5 men from a range of social backgrounds spanning the council estate to the private school, all in their very early 20s, coming together to write some of the most beautiful, complex, ambitious and enthralling music any Rock band until then had. It boggles the mind that such a high bar of quality had been set by such young, relatively inexperienced musicians.

What makes it more incredible is that, for that type of Rock/Classical crossover Progressive music, nobody has really topped them in the 5 decades since. Those initial albums remain a pillar of what’s possible when you throw the rulebook out the window and really focus on creating something incredible.

These things never last, though. That line-up had too many personalities to happily co-exist.

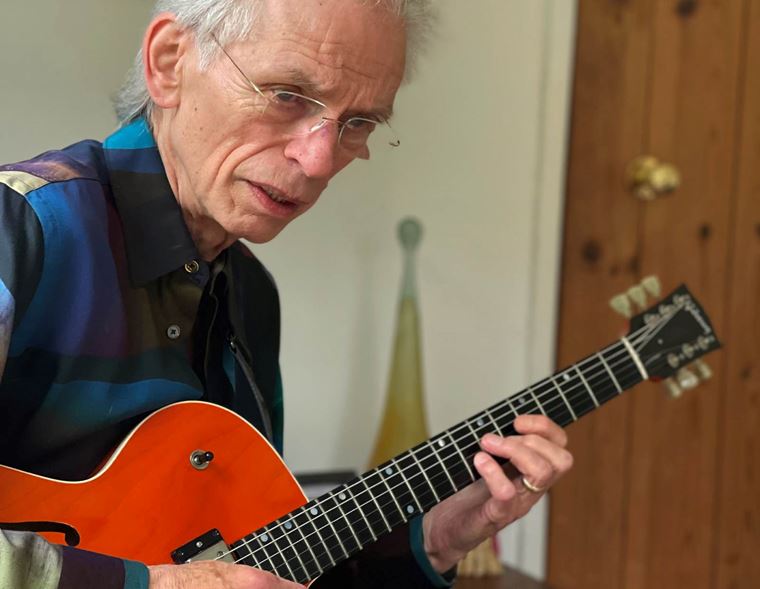

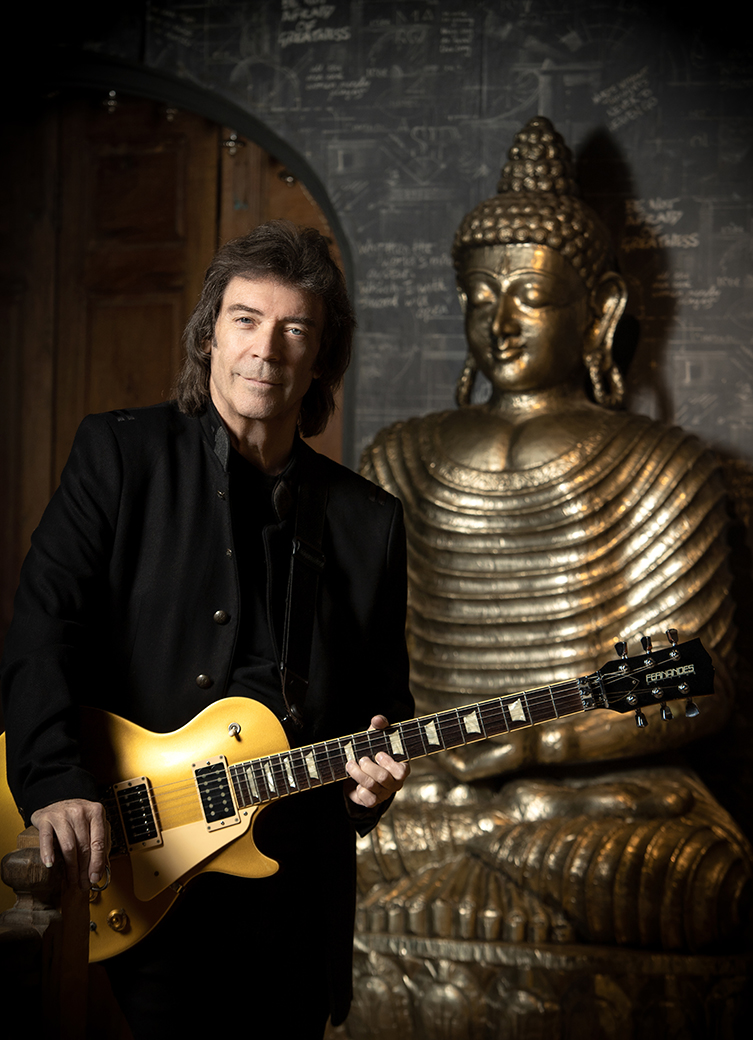

The golden period for early Genesis was five or six years. Of the 5 young men who made up the band - for those who don’t know - several moved on to other things: the singer became Grammy-winning solo artist, human rights activist and World Music champion Peter Gabriel; the drummer became 80s megastar Phil Collins; the bassist went on to become ‘Mike’ from Mike and the Mechanics; and lead guitarist Steve Hackett went on to take command of a prolific and prodigious solo career that has seen him play classical guitar with the Royal Philharmonic, start bands with Yes’ Steve Howe and bring together disparate musical ideas from across the world on both albums and live performances that have seen him play at the Royal Albert Hall and take a 40 piece orchestra on the road.

Those ambitious early days certainly proved to be a template for later life!

Of course, as you’ve gathered from clicking through to this page, it’s Steve we spoke to recently. A few years back we were lucky enough to get an email interview across to him (click to read our previous Steve Hackett interview), but this time we were able to get him on the phone for a proper blether. Much better!

Steve’s an incredibly interesting man. As you’ll find out when you read this interview, he is one of those people who goes out seeking experiences, and uses everything he learns in his art. Over the course of literally dozens of albums, Hackett has explored several rich veins of exotic musical styles that encompasses Spanish, Greek, Celtic and Arabian folk styles, along with his own love for classical music, rock and other disciplines.

Truly, in terms of his lead guitar playing alone, Steve is one of the greatest in the world, and certainly deserves to be spoken of alongside Clapton, Beck and Page. This doesn’t even take into account his sublime and masterful classical guitar playing, which is peppered throughout his Rock albums and even featured on several full-length records. It’s one thing to be one fifth of Genesis’ most revered era (that is not an easy job...), but quite another to write a suite of new music for classical guitar and orchestra, based on Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and performed by the Royal Philharmonic with Hackett leading on nylon guitar!

Not many people can do that, frankly.

Our occasion to be speaking to Steve is the publication of his autobiography, A Genesis in My Bed. Yes, the title’s an odd one, but it makes a lot of sense once you read the book! After devouring the text in a mere weekend (the sign of a great read), I got an excellent sense of the man behind the music. There were so many tantalising stories, ranging from foreign travels so experiences with psychic, as well as plenty about this Genesis and post-Genesis years. Indeed, his life and career after Genesis is arguably more interesting. There was so much to ask!

Tina Korhonen.jpg)

During lockdown, Steve has been admirably busy, putting out regular video content of chat-tracks and some exclusive playing too. Where does he get the energy? These videos were provided even more insight to the this most restless and colourful of artists. Needless to say, I binged the lot, in order to make myself more aware of what to touch on and maybe what not to, given what’s available for people to see online already. Hackett fans are currently pretty spoiled for content!

A few Friday mornings ago, I received the call from London. As I sipped my second morning coffee, Steve and I spoke of the relative merits of vintage Les Pauls, the importance of getting your work out there no matter what, and of just what lies beyond the material realm we call our physical reality...

Steve Hackett Interview

guitarguitar: So, I was thinking we could talk a little bit about the book first and then move on to the guitar chat?

Steve Hackett: Yeah, that’s fine!

GG: Fantastic. So, first of all, the lockdown! You’ve been very busy posting videos online a lot. How have you been finding the lockdown, personally?

SH: Um, I think that’s the visible side of it: videos, track chats, doing a little bit of live playing, but the main work has been recording a new album. Mainly nylon guitar and orchestra. That’s going very well, it’s a very productive time for me. So, on one level, it’s frustrating that you can’t socialise in perhaps the way that most of us do – get those breaks, go and see friends and family - but on another level, it’s been very concentrated. It’s almost like going away somewhere to make an album.

GG: Mmm.

SH: You go off to another location, like Holland, as I did before, or once in the States, or off to Sicily or Hungary or something, and coming back with something. So, isolation, in a way, certainly kept me on the plot.

GG: That’s fantastic.

SH: It’s been a very inspired period in so many ways. I find whenever I’m doing nylon stuff, I usually give in to my romantic leanings. But there’s also an aspect of what I’ve been working on which involves various places around the Mediterranean, the Arabian influence and the Harmonic Minors. Sometimes, instruments that I’ve recorded at different times have come into play with this. It’s not just another acoustic album, or another orchestral album, it has the other elements which give it the feeling of travel, and I’m only too happy to do something that’s slightly different, so, for me, I wanted to keep it a far cry from New Age music!

GG: Hahaha!

SH: For me, it doesn’t move much. So, I don’t think it’s...it’s not really music for massage and hot oils! It’s not the sort of aural equivalent of aromatherapy. It’s not that: it’s sort of, feelings and dreams, really.

GG: Yeah, that’s actually touching on several of the subjects I was hoping to cover with you!

SH: Right!

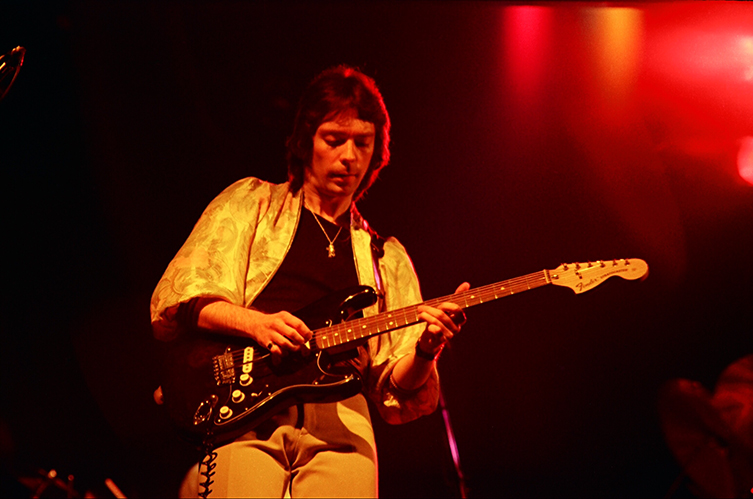

(Photo: Armando Gallo)

GG: I’m sure we’ll get back through it, but since we started here: the term ‘world music’ seems a bit pejorative to me, because what music isn’t? But, a lot of your influences are exotic, and you do make use of a lot of amazing, colourful instruments from all over the world. I read your book last week, which was fantastic, by the way, I rattled through it...

SH: Oh, I’m glad you enjoyed it, thank you!

GG: Oh, very much! I read a lot anyway, but I got through it in about three days, which is a great sign, haha! At the end of it, you talk a little about an Ethiopian influence that was going to creep in. Is that part of what you’re taking about with this project?

SH: Well, so far, with this project, the journey that we made with the Ethiopian thing showed us an awful lot. There was a little bit of music that cropped up, like at one point there was a guy sitting down, playing a lyre, just a few strings on this little instrument, and he was playing it really beautifully. At the same time, there was a prayer call going on so in the distance you’ve got (makes an exotic vocal sound) going on! So, yeah, I could use that! (laughs) This is what happened on location, this is rather nice! But at the same time of course, you’ve got, you know, a clash of culture going on.

So, I was really able to access music in isolation. There’s a lot going on in Ethiopia. We met tribes: that was extraordinary. I was hoping to come across more tribal drumming, but it was just kids and it was very rudimentary, so the idea of becoming the great explorer and heading off with your khaki shorts (laughs) hacking away at the jungle, is wasn’t quite like that! But we had some hairy journeys and some of it was extremely difficult to access. I think the inner journey stays with me much longer than the outer journey, in terms of how that’ll affect stuff that I’ll do, but in terms of ‘did I come back with Ethiopian drums and voodoo ceremonies?’, I’d have to say no (laughs) but the magic is going on inside me. It was one on the most fantastic trips – more of an expedition than a holiday – so, yeah, there were those moments.

It got tantalisingly close to getting the music of that place, but not enough to be able to say, ‘here it is, yeah, I’ve got it’, and present it to you right now, whereas other places: Azerbaijan, Hungary... I’ve been able to access things from there. The Duduk from Armenia and various other things from Hungarian gypsy violin...those things have been more accessible. Morgambe, which is a sort of Arabian Jazz where they improvise new rhythms and break out into solos. I’m only a beginner with that, I’m only beginning to understand some of that. So I’m trying to coalesce these sorts, and sometimes collections, of things, these collages, into something without...you know, try and keep it on a tight rein, without having it just ‘’go and having people go ‘well that’s all well and good, but where’s it leading?’ etc.

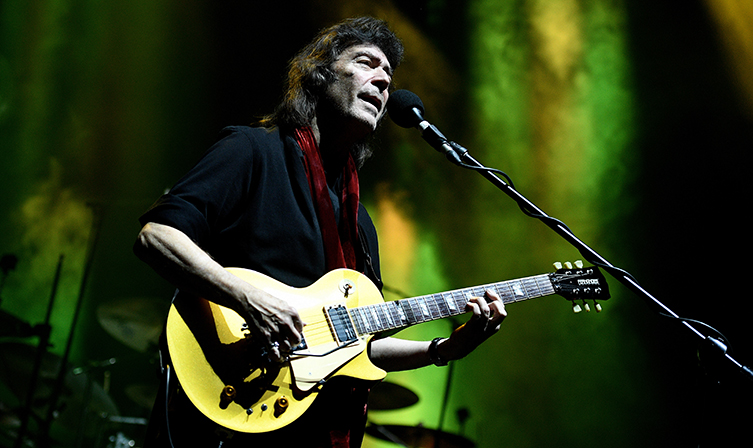

(Photo: Tina Korhonen)

So, um, in a way, I think possibly having grown up with at least two schools of thought going through my brain – and those were Blues and Baroque – one’s a through-composed medium and the other’s mainly about improvisation. What links them is that they’re player-based. The great exponents of those things: Segovia and Jimi Hendrix, although they’re worlds apart and schools apart, they are still player-based. You’re still working the fretboard for all that you can garner from it, and if you set prejudices to one side, I’m sure they could both learn quite a lot from each other.

GG: Certainly!

SH: So, I try to take a very broad-minded approach to music and particularly guitar playing.

GG: Yes indeed. Of all the musicians who come under the umbrella of Prog - for want of a better term – it seems that you are the most open to other traditions, and indeed very quick to master them. There are so many guys who can play fantastic electric guitar solos, but your nylon string classical playing is pretty much unparalleled. That’s a side of Modern Rock music that a lot of players lack the discipline for.

SH: I think it’s probably an abandoned place for most people. They think ‘oh, I’m not going to bother with that!’ Um, because there’s been so much work done by people who came about before. You know, flamenco, the work of Paco de Lucia, or in an earlier era, Paco Pena. Blistering stuff, fantastic! But then there’s the side of things that, even before I was in Genesis, when there was this big emphasis on writing, we were all aspiring writers, I had this sense that melody was really, really important, and how knockout that could be!

GG: Yeah!

SH: You know, a great melody and one person playing a guitar for instance, or a piano - any soloist who could access harmonies or had any kind of orientation towards technique – that could be a heady combination. And the idea of the guitar as a small orchestra is something that I think is forgotten. You’re not farming it out, if you’re sitting down playing that stuff: it’s just you and the fingers.

GG: Yes, there’s nothing to hide behind.

SH: Yeah! Well, I’ve always tried to play outside my capabilities. I can fumble away with the best of them and make terrible mistakes, particularly when recording, but then, it’s a bit like writing a book: there’s no such thing as writing, there’s only re-writing. If you want it good you’re going to do it again, so I’ll play and phrase and think: ‘Yeah, it’s not bad, there’s a bit of a scrape here, and a I could’ve gotten the dynamics better there’. I’m just looking for that extra bit of magic, where it plays me, and I think, ‘oh, I didn’t know it could do that!’ Sometimes it’s just donkey work: you’ve just got to try and get it in time and in tune and have all the notes heard.

"The element of surprise is the best of Prog music for me"

GG: Yes.

SH: That’s a kind of standard, isn’t it? (laughs) Beyond that, you’re thinking: Okay, these are the notes, what makes them magic? Is it the tone? Is it the choice of notes?

GG: And for the classical guitar, then: it’s such a different sound and touch from a steel-string guitar. The tone suggests such a different set of visual images in your mind. Now Steve, are you naturally right-handed? That’s a significant factor.

SH: I am right-handed, yeah. I was thinking, funnily enough, in terms of a six-string steel player, playing with a nylon sensibility, was John Renbourn. He would play the guitar and suddenly go to the bridge and make the tone brighter, and he was using fingerstyle. Some of those influences were everything from medieval music to ragtime and Indian music. I remember reading an interview a few years ago and he was saying ‘oh, my playing’s a hodgepodge! He went back and learned to do it all properly, lessons and everything, so it’s a little bit like Eric Satie, learning how to do it ‘properly’ after he’d been doing it wonderfully instinctively! Nothing wrong with people going back and doing lessons, but sometimes we love them for their early work, and the stuff that is not necessarily aware that it’s breaking rules. I’m all for that, and one man’s hodgepodge is another man’s progressive music! So, the idea of inclusion, and that all these styles can be put side by side, can surprise you, especially when you’re using acoustic and electric instruments. For me, that’s all part of the joy of it: the element of surprise is the best of Prog music for me.

GG: Yes, entirely! The word that I would use with a lot of your music is ‘juxtaposition’. Certainly, on your most recent records, Wolflight and so on, there are lots of surprising changes, but there’s a real flow to it. I was wondering, going back to what we were talking about a second ago about the lost art of including the Classical music, there’s a real specificity to the colour and texture it gives when juxtaposed with Rock music. And there’s also the historical context to the instrument: how great is that to be able to drop that into the middle of a song? That kind of exotic journey isn’t something we get much with music these days.

SH: No, I think that you don’t find it as much now. It’s part of the legacy of the 1960s, particularly in the late 1960s when music started to show its Classical roots, so that that was no longer a guilty pleasure, but a chance to incorporate it into the mainstream. To not have any prejudice towards any one particular genre. The British bands, I think, were in the forefront of that. Procul Harum, who could orchestrate as well as do things that were really soulful, they were particularly brilliant. You get in one band a mixture of everything I was talking about: Prog and Blues together! That’s it!

GG: Definitely! It’s the ambition isn’t it? That’s one thing that blows my mind about what you guys did in Genesis when you were 21 or 22 years old! The ambition that was there! It’s one thing to be a good musician and be able to play it, but to actually write that stuff and put it together, that’s kind of almost unheard of these days. Do you ever look back and just think, ‘Wow, we were really smashing it quite hard back then!’ Haha!

(Photo: Alan Perry)

SH: Oh, sure, yeah! It wasn’t easy, I mean those rehearsal sessions sometimes became battlegrounds (laughs). Um, at times, some of the fireworks were not just musical! There were definitely the power-play aspects of it, but there was passion, and so when you get a number of creative people all come together, who were all eventually able to do it on their own with different teams - because none of us works in complete isolation, there’s always a dialogue between yourself and one other person, it seems to me – sometimes those Genesis pieces were forged in argument. That 5-man team, that lasted from ’71 to ’75, it was never going to last forever.

GG: Right.

SH: Composition by committee, it’s very difficult to weather. Turbulent exchanges from people who come from a very tough background, and I’m talking about the privileged background that forces you to become either a world leader or end up an absolute psychological mess, really. So, I think the Charterhouse background (private school attended by Genesis members Tony Banks, Mike Rutherford and Peter Gabriel - Ray) wasn’t easy for those guys. Fortunately, I didn’t have that. I was driven but I don’t think I was as competitive as the team that I was working with, who were going at it like an airborne version of...what’s that game in Harry Potter?

GG: Oh, Quidditch?

SH: Quidditch, that’s it! (laughs) I’ll try and unseat you from your broom! Yeah, I’m parodying what it was like, but I think that it was strongest when we were co-operating with each other. I think some remarkable stuff was written at that time. I’m very proud of whole swathes of it.

"Those Genesis rehearsal sessions sometimes became battlegrounds: some of the fireworks were not just musical!"

GG: Rightly so, there’s some exceptional music. To somebody like me who was born in the 80s, that music is quite timeless: timelessly excellent Rock music, rather than something that Punk came along to destroy or whatever. History, through my eyes, has given the music it’s place on the pantheon.

SH: I think that’s a nice way of looking at it, and I have a similar thing, you know: I was born in 1950, considerably before you were, but when I look back at what I consider to be ‘contemporary’, it’s got to be anything that I’m currently interested in.

GG: I agree.

SH: So yes, avant-garde is anything I’m currently interested in, which means I might be listening to William Byrd from the 1500s, or Bach or the Romantics, you know? People born in 1685, Bach and Handel, all born around that same time, as if they’ve all come down together. I find a fascination with that and I would personally be more drawn to that and find it more contemporary than the music from, say, the 1930s! But others would take issue with that: ‘No, no! That was the golden era, when I was a boy!’ and all the rest! (laughs) It’s very hard, isn’t it? Music is suggestive and what you grow up with, you tend to think as ‘this is the great music, this is what mingled with my hormones and of course: this is the real music!’ So, I find it strange when people, who might be interested in the whole pantheon of music, say ‘but I grew up in a time when Frank Sinatra reigned supreme’ and, you know, that’s always going to be something great for me, but I won’t necessarily be in step with that. I’ve opened myself up to it more with the passing of time. Suddenly I’m aware of the role Nelson Riddle had to play, the arrangements. The clothes are very important, the string arrangements.

GG: Yes, very much so.

SH: (laughs) And then you listen to that and say: ‘Ah, yes, OK: witchcraft!’ There’s an influence from the French Impressionists with the orchestral work. So, it all has to look backwards. We were all forced to be historians, and look back to an earlier time and say: ‘Is there anything of value here? Can I take this? Can I take this forward?’ It’s no good thinking you invented music because you bloody well didn’t! (laughs) You can’t! You can only juxtapose what’s already happened.

GG: Yeah, yes absolutely. Talking a little about history, and of course the magic of music, when I was reading your autobiography, one of the things that came through to me again and again – and funnily enough in this conversation this morning too – is the word ‘magic’. Some of my favourite parts of the book are the magical experiences you describe of everyday life, and in particular the parts about you visiting the funfair at Battersea park, and also your journey to Canada. It’s like when you read a Salman Rushdie book and he talks about the magic that’s in the fabric of the everyday. Is that something you consciously carry over into your work as a composer?

SH: Oh yes, yes! We are have these magic moments when we look back over our childhood, you know, when the clouds seem to lift: suddenly there’s a perfect moment when all of your senses come in, in the most pleasant way and it’s before you have any romantic experience, when you’re looking for a partner. You’re just trying to make sense of this world of seemingly random impressions. So those events – the funfair that was just on the other side of the river from me, and getting to work there as a 12 year old: that for me was heady stuff! Even as a 12 year old, I was remembering, and it all mixes with the music I was hearing at that time. The guitar bands that tended to rule, and even before the Beach Boys there was Jan and Dean, all of that!

"For God's Sake, don't let anyone - either real or imagined - say 'you can't do it'. It's so important. If you love it, you can do it."

GG: Ah, yes.

SH: It’s difficult to say, you know, lots of tunes that were either great because the Beach Boys were doing complex harmony work, as were Jan and Dean, the Everly Brothers, Roy Orbison, that’s all wonderful stuff for me, um, but then at the same time there was so much more! Even as I try and pin it down just now, it seems to fade and recede. Sometimes the tunes were very, very basic and you could literally play them on two strings of a guitar. I’m thinking of Pipeline by the Chantays and the other one by the Safaris, Wipeout, and those little tunes were perfect for cutting your teeth when you were first starting out: ‘Look Mum, I can do this!’ (laughs) But years before that, I was playing harmonica from the age of 2, trying to play tunes and deadly serious about it as well: it used to make people laugh, that I was so serious! (laughs) Yeah, barely able to stand up but at the same time, I had my Dad’s harmonica. Back then I remembered being frustrated because I realise what the magic thing was, the thing that gave notes direction, and I only found out years later that it was chords! They’d make the same note go up or down!

GG: Yeah, of course!

SH: What an incredible bit of alchemy that was! The idea of chords and harmony. Even now it’s a mystical quest, isn’t it? Trying to sort out chords that move you.

GG: It’s never-ending! Well, happily, that dovetails into another question I was going to ask about an interesting thing. Now, I don’t want to give too much away to those who should go and read your book, but leading on from what you were saying about the mystical combination of chords and melody, there’s a part where you talk about an experience you had with a South African psychic who related specific visions he had to you, which them became inspiration for your guitar parts on Genesis’ Firth of Fifth. Do you often visualise your parts before you write them?

SH: Well, it’s something that I remember I was involved with, a band called Quiet World. Three brothers who’d grown up in South Africa, but they were English. They went to South Africa, their father was a Medium, he was a psychic, and he used to receive spirits. He’d talk in different voices, speaking in tongues and what have you, and he used to send the tapes back to his sons in London. Some of it was the idea of lyrics but at the same time, it was also talking about the spirit of music, and various characters that were mentioned, and the idea of music functioning like a bird flying above the sea. When I was putting together the Firth of Fifth solo, I thought it was a way to make it start, in a way.

The song was supposed to be about water and so this droplet of an idea was to sustain a high F# over a chord sequence that’s moving from E minor to D major. The thing about guitars and feedback, perhaps nine times out of ten, it might, if you’re playing in the right spot, give you the note that you’re after, but it’s very hit and miss.

So, I was working with that, and I thought ‘let’s hold it before the theme comes in’, so you have a moment of calm, a moment of stasis from the guitar. Then it moves, then the wings start to move, and it goes up and down on bends and all the rest. So, it gave it almost a kind of...I’m thinking of Indian scales and Arabian stuff, and that melody has got that, it’s got a little bit of a Bach influence in there: it’s Tony’s construct and my variation. It was a hell of a good melody to be able to play with a band that had newly acquired certain things. I mean, it wasn’t long that we’d acquired the organ and mellotron, for instance. A heady mixture! A bit of vari-speed, 12-strings, recorded at half-speed, bass pedals by Mike and me free to fly with this melody on the top. I think it was such a good melody, that I had a range amount of freedom to play a three-minute solo! (laughs) No one competing with me there!

GG: Yeah!

SH: I know that Tony was particularly proud of the way that one came out. He liked what I did with it.

GG: No wonder: it’s incredible.

SH: He certainly would’ve been extremely vocal if he didn’t like it! (laughs) I guess, certain bands have that. I think perhaps – I was thinking about this today, having had known them both – Tony Banks’ role in Genesis was a bit like Robert Fripp’s role with King Crimson.

GG: Interesting.

SH: Yeah, there’s a sort of disciplinarian aspect of iron will and single-mindedness, but at the same time, there’s a romantic hiding in there as well. So, it’s interesting when you get that mixture of passion and intelligence and will, you’ve got to really try hard to do something that gets through the sensor. And, to some extent I inherit all of that and so when I’m listening back to things now, I’ve got to be my own severest critic and say ‘well, actually, you could do better there, Hackett’, you know? It’s the inner Schoolmaster!

GG: Haha, yes!

SH: From the report, who says ‘Could try harder’. (laughs) It’s important to distinguish the difference between that and the ‘Internal Invalidator’, which says, ‘you’re completely useless, you’ll never be any good’ and I do not have the Internal Invalidator: I am luckily born without that gene. That devil on my shoulder. It’s the thing that prevents most people becoming geniuses, you know? You don’t even get off the starting block if you listen to that small voice of invalidation, and... whatever it takes: go get some therapy, see a hypnotherapist. I had to, at one point, but for God’s sake don’t let anyone - either real or imagined – say ‘you can’t do it’. It’s so important. If you love it, you can do it.

GG: That’s brilliant! That’s such a fantastic thing to hear you say, and very important for others to hear it said. Now, on a slight tangent, before we move onto the guitar stuff, I wondered if I could ask about your astonishing debut album, Voyage of the Acolyte. Your amazing song Shadow of the Hierophant seems to be in two parts, and from reading your book, I noticed also that on the same album, the songs The Lovers and The Hermit use the reversed version of the same melody that the other one uses.

SH: Yeah.

GG: So, what I’m thinking of here, Steve: it’s a bit of a random question...

SH: Sure.

GG: Because the Voyage of the Acolyte is based on the Tarot, I wondered first of all, if you make much use of tarot readings in your personal life, and also, after that, whether those things I just mentioned there are to signify that esoteric principle of ‘as above, so below’?

SH: Yeah. Well, these days I only do it very, very occasionally, and I think it was maybe a month or two ago, Jo and I – my wife and I – did a tarot reading and it seemed to be extremely relevant to what was going on now. It was basically telling us to move slowly and cautiously, and there seemed to be warnings in it. I realized that you can read very much what you want into the cards.

Tarot gave me a framework to work with when I was doing that first album. I thought, ‘Ok, if each one of them is a card then there’s a story behind this: I can make this work’. It’s difficult, isn’t it, because at what point does any album become a concept album? It’s got to be some point down the line: once the journey is already started, you realise what it’s all about, so I think if it’d have had no notes of music written and was going to superimpose that idea on it, I don’t know if that would’ve worked, I’d have probably found it an encumbrance, but I found a way of explaining where I was at with it.

Obviously, there’s a lot of classical influence on that album. I had a wonderful time making the album. I was living back home with my parents after my first failed marriage, and my brother john - having been bright enough to get into Cambridge to study languages, after six months decided he didn’t want to do that and wanted to do music full time - so he was back at home. We were batting ideas off each other, and the chance to work with him professionally for the first time was terrific. Obviously, we’d grown up together, we’d shared all sorts of things, the same guitars, and he was turning into an extraordinary flute player. So that was his debut on that album, and what stunning playing there is from him!

GG: Yes, indeed.

SH: It was from a time when I’d not learned to pace myself, and we weren’t able to record until after 6 o’clock at night because it was a government building at the bottom of Aviation House in London’s Kingsway, a place where Fleetwood Mac had worked and I believe Deep Purple had some involvement: they owned it at the time or had a lease on it. So, starting work at 6 o’clock every night mean that they turned into night sessions, by the time you walked in and organised yourself, so we were coming back very late at 3 or 4 in the morning and then they were doing building work in the flat upstairs so I was maybe getting a couple of hours’ sleep a night.

"There's no such thing as the ultimate guitar sound. You're always chasing something that you think some other guy's got"

That wasn’t great, but it’s happened time and time again in my life: I learned to pace myself years later (laughs) but enthusiasm was everything in those days. I was in my mid-twenties and I was in full flight, loving the process of doing the first solo album where I could look to others for input, but I had the final say. The reaction to it was very, very good and I had co-operation from Phil (Collins) and Mike (Rutherford), so three out of four Genesis guys were working on it at that time. So yeah, it was a great time!

GG: Yes, and what an incredible album it remains! Now, why don’t we move onto some guitar questions for all the fans out there?

SH: Yeah!

GG: I watched your documentary video about the making of The Night Siren album recently and, because I’m a big fan of pedals, I had a good look at the scenes where we can see your pedal board! I was surprised to learn that you weren’t using any amplifiers to record, instead going direct! Was it the Sansamp GT2 that you’re using for your main lead tone?

SH: Um, yeah, there’s that...um, I had two studios at one point and then I found that working at home, when there was a dispute over studio ownership, I basically thought, ‘Well, if I can work in the living room, I’ll do it!’ and that was a time when I was working with (Yes bassist) Chris Squire. For the first time, I was suddenly forced to work with amp modelling and virtual speakers and all the rest.

GG: Mm-hmm.

SH: What we were finding was, we were able to A/B this against what amps were doing and there was very little difference. I thought: working like this, there’s no tyranny of volume. As it happens, I’ve got some wonderful Engl amps at the moment, that I’d dearly love to record with, but I know what room they sound best in, and it’s a rehearsal place in Putney, so I’d have to be recording guitar parts there. But there’s a really sizzling top to them! I’m using them live and finding that they have a very good sound.

"The idea of chords and harmony: even now it's a mystical quest, isn't it? Trying to sort out chords that move you"

I think the room plays a big part in recording amps. The room that you’re in: what’s it like? The floor, are there other things in there? The placing of the mics, what mics, all of those arcane things, and I can’t throw light on that. I mean, right back to the days when I was working at Aviation House, I remembered that John Aycock, the engineer, said; “Yeah, Deep Purple work in here, and sometimes they have a mic over the back of the cabinet”, to catch the parquet floor, and the way that interprets the sound. I thought, ‘Ah, that’s an interesting combination, isn’t it? Marshall amp, Stratocaster...parquet floor? (laughs) Mic over the back!’

GG: Brilliant!

SH: Yeah, mix that to taste with one at the front! You’re gonna get an ambience and a woodiness that good guitarists like a lot: they like the whiney aspect of that sound, if they are a Rock player. It lets the sound breathe.

GG: And you find that you get enough of that with the modelling?

SH: Well...I think that I’m getting close. There’s no such thing as the ultimate guitar sound. You’re always chasing something that you think some other guy’s got (laughs). It’s always this imaginary thing. I mean, for me, for a Rock guitar sound, it’s a cross between a Rock guitar, a cello, a violin and a brass instrument, thank you very much! I don’t want much, do I? (laughs) You know, I want all those qualities in there. I want to have the fullness and the edge of brass but the whine of those other stringed instruments.

GG: Yeah!

SH: You want it to have heart, and proportion, and you want it to live and do all those things. Sometimes you get it! And sometimes, that sound mixes well with other instruments: other times, those other instruments soak it all up.

(Photo: Lee Millward)

GG: Yes, that’s very true. It’s a constant push and pull. So, your main gigging guitar that I see most often is the gold Fernandes, which is like a Les Paul, and you’ve also got that beautiful vintage Gibson Les Paul.

SH: Yes!

GG: So, what I wondered is, as a player, so we’re not talking about the incredible value of the Gibson versus anything else, I just mean as a guy playing a guitar, how do you find the comparison of the feel and the sound of each of those instruments?

SH: I think somewhere between those two guitars, you’ve probably got the perfect instrument. Sometimes I pick up one, sometimes I pick up the other. I think at home, when I’m playing with my little Peavey practice amp, if I’m honest, I think that the sound of the Les Paul is better. But then sometimes when I’m working with a virtual amp, and it’s giving me all of the thickness and the ‘leatheriness’ that I’m after, there is very little to choose between them! I think that they produce different things. You’ve got more tonal control over the Les Paul but then the Fernandes, because it’s got the Sustainer function, that can also function as a tone all of its own.

GG: Yeah.

SH: You’ll never be able to roll off the top that you can with the Les Paul because there’s a compromise with the Sustainer pickup functioning the neck pickup as opposed to the bridge pickup. Essentially, you’re getting most of the sound from the bridge pickup, it seems to me, and the sustain from the neck pickup. Sometimes, with a very light touch, on the second string, or sometimes on the third string, I can get an upper harmonic in there but it’s different from the pure harmonic of flicking the switch, so you get that screamy harmonic. It’s another kind of sound: it’s almost giving you an extra octave.

GG: Yes!

SH: And it sounds like you’re familiar with the Fernandes, so you probably know exactly what I’m talking about, but it’s only with time that you get to learn what that thing can do, and what each of them is capable of doing.

GG: Mm, certainly.

SH: It’s not that I’m anti-Stratocaster or any other kind of guitar, it’s just that I’m best at operating those two!

GG: Totally!

SH: I do own a Strat and I’ve recorded it from time to time, but my go-to tends to be the Fernandes, and if I don’t get it from that, I’ll look for something else. But you know, there are tracks that I’ve done in recent times that I’ve used nothing but the Les Paul. On At the Edge of Light, there’s a long solo at the end of a track called Those Golden Wings, and I went to the Les Paul for that. I thought, ‘yes, I’ll try and get it out of the Les Paul’ and it’s a fairly mellow tone on that. I could’ve used more ‘top’ on that and make it more blistering, but I wanted to keep it melodic and...when to ‘machine gun’ and when to ‘woo’ it: you’ve got that choice, haven’t you?

GG: Yes! Those decisions are what distinguish you.

SH: Yes, and guitars can do both! They’re remarkably resilient, flexible...I’m looking for the word...

GG: Versatile?

SH: Yes! Versatile instruments. I guess that’s why they’re so popular!

GG: Definitely! Now, I only have a couple more minutes with you Steve, and one thing I did want to kind of jump across to was something you mention a good bit about in your book. We spoke about the tarot, we spoke about the psychic, and there is an intensely spiritual side to a lot of your life. You talk of practising Transcendental Meditation and so on, so one thing I really wanted to ask you is: what does ‘consciousness’ mean to you?

SH: Well it’s interesting. Those that have apparently died and come back, been revived, um, there’s a book by a guy called Eben Alexander. I read his book, which became a best-seller, and I’ve read a lot of the work of Dr Raymond Moody, who’d written a lot of stuff in the 1970s about out-of-body experiences, and people who’d died and been resuscitated, and Eben Alexander came up with the concept of, you know, ‘what is consciousness?’, which is the very thing you’re asking me about. Is consciousness merely local, i.e. ‘I am conscious therefore my experiences are the sum of all experiences for me personally’, or is there such a thing as universal consciousness, where we transcend ourselves? And is there life after death, or other realms and all the rest?

In terms of that, I have to say that I come down firmly on the side of the idea that the plane of existence, or the consciousness that we have, is not all that there is. I do believe in spiritual healing very strongly. I was very impressed by a number of people who treated me for various things and found, magically, that everything I had, all the pains I had, went away and that was just phenomenal.

So, I have to say, I agree with Shakespeare: ‘There are more things in Heaven and Earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy!’ I’m with him on that one, I think he was onto something!

Letting Bill Shakespeare take the last word seemed somehow very appropriate. Time had positively flown out the window for me, anyway! I had already sped past my allotted time with Steve, which he had kindly allowed me to extend. As always, I had plenty more to ask, but that will need to wait for another occasion.

Steve has been so generous with his answers: I took him down some unusual roads, but he was happy to give me full and considered responses for everything I brought up. I think this displays much about his overall attitude and openness to the possibilities and avenues life has for us all. It was a very illuminating conversation and I came away from it with a much better impression of not only the man, but the spirit that lies within and creates the beautiful music that he’s known for. We got loads of guitar chat in, but so much more besides, which hopefully gives more weight and value to the piece.

Steve is currently busy with his new classical album and is also continuing to regularly post chat-tracks about solo songs and Genesis music. The easiest way to keep up with him is via Hackettsongs, the official Steve Hackett website. His autobiography, A Genesis in My Bed, is out on 24th July wherever books are sold. We highly recommend reading it! Steve will be back out on tour when it’s safe to do so, with new music and more amazing performances.

We’d like to thank Steve for his time, and for his kindness and grace in giving us such vivid and thought-provoking answers. We’d also like to thank Sharon Chevin for all of her help in setting this up.

Thanks for reading! If you'd like to read more of our exclusive artist insterviews, please click and search through our Interviews pages on the site.