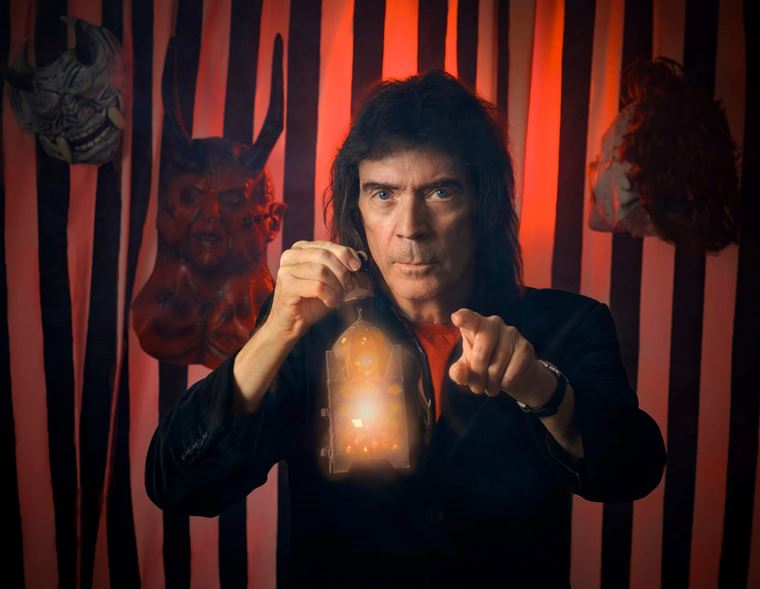

"Your Own Concept is the Only Limitation There Is" JO QUAIL Interview EXCLUSIVE!

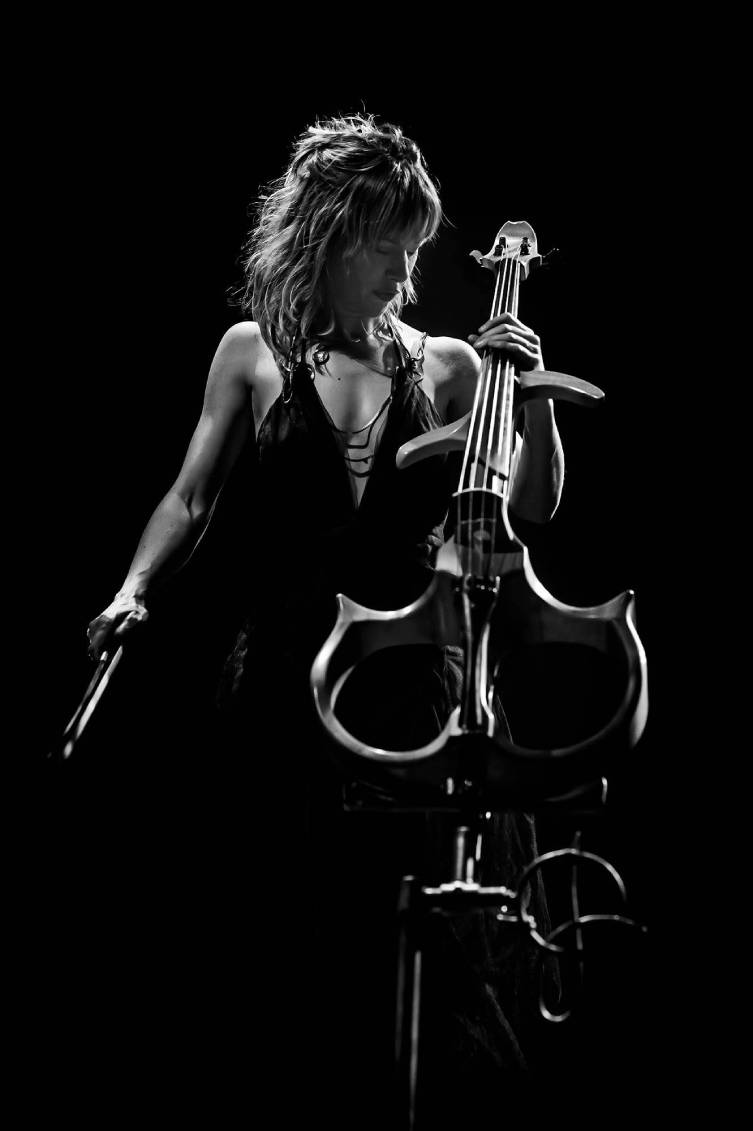

Jo Quail is a performer and artist unlike any other. Armed only with a cello and a few devices at her feet, she is able to summon a universe of sound from the mellifluous to the downright diabolical, and she does it all live.

Touring with artists like Heilung, Wardruna, Boris, Myrkur and Amenra has put Jo in front of hugely appreciative audiences who recognise the fire of invention and the spark of genius that fuels her compositions. Her charismatic performances are almost like watching a musical witch doctor summoning sonic spirits and corralling them into a tornado of sound that builds from nowhere.

She’s quite an artist!

It’s obviously not the most obvious thing in the world to feature a cellist in guitarguitar, but then, the same artistic logic that makes her a great choice to tour with doom metal bands is the same logic that leads me to think many guitarguitar people will love what she does. The very idea of using two BOSS units - a GT-1000 and an RC-600 Loop Station - as her creative tools puts her in direct company with ourselves, after all.

Jo is also amazingly interesting to talk to, and very eloquent when expressing her unique views about music. In fact, she’s about as ‘guitarguitar’ as it gets in a great many ways, and it’s my pleasure to feature her on here. Read on, because whether you know the first thing about a cello or not, this interview definitely applies to you!

(Photo: Peter Troest Vega)

Contents

Touring with Doom Bands & Gratitude to the Metal Community

Co-Headline Tour with Jon Gomm

Jo Quail Interview

Guitarguitar: So, why don’t we start with the early days? What brought you to music? And what brought you to the cello in particular?

Jo Quail: Well, I began in music through my mum. We had a piano at home and my mum taught me to play when I was three or four: I have a very clear memory of sitting with her and playing middle C, you know? (laughs)

At the time, ILEA (Inner London Education Authority) were running a program for inner london primary schools which eventually evolved into the Center for Young Musicians, but at the start it was a free program rolled out across london. They gave string teaching to anybody who wanted to do it, free. It was an incredible gift that they gave.

So, I started to play cello, and the only reason I played cello was because there was a gap in the cello class and there wasn’t a gap in the violin class! I’m forever thankful for that gap! That was it, really: my whole childhood was spent doing music, playing cello outside of normal school time, but of course all my friends were doing it as well, so it didn’t feel unusual or anything. It felt quite normal: we’d all go to Saturday music school for lessons.

I continued the piano as well, of course, but one of the most important things that the Centre for Young Musicians encouraged was what they called ‘general musicianship’, which was essentially improvisation. It was a very freeing approach to teaching music, and that is what I carry with me now.

GG: Interesting! In that case, was the piano playing with your mum something you did informally?

JQ: Informally, we always had a piano - which is a very lucky thing to say, I know - and my mum is a non-professional musician, but if you could be a professional musician with your passion and enthusiasm then she would be, absolutely!

GG: Cool, that’s awesome. So, you’re going through school playing cello and I’m thinking - this is my subtle segue into your tours these days with metal bands - presumably you were listening to a bunch of classical music because it related to your cello playing, but was that your taste as a younger person? Were you into other stuff too?

JQ: Well I was into all sorts of music - as I still am, actually - but metal has always had a soft spot for me, but you’ve got to bear in mind that the era for me which was the richest was probably 1987! (laughs). That was a formative kind of year. So I always, always played classical music and in the largest sense of the word, you know, but when I was at school, well, I remember one of my earliest memories was Pink Floyd, Another Brick In The Wall being in the charts, such as the charts were at the time. My dad had always been very into, like, the Kinks and Tony Joe White and Pink Floyd and stuff like that so he would play those records and my mum would take me to classical concerts, little recitals at a local sort of house thing that we had.

And I remember - this will probably sound very unimpressive to your readers - but I clearly remember seeing an advert on the television for a compilation called Pure Soft Metal, and on this advert they'd taken an extract from Wasp’s Forever Free and you can laugh and it's fine (laughs) but I'll very happily stand by the fact that Wasp were one of the most important bands to me, so that's my version of metal. I don't know enough to appreciate some of the newer genres of metal that are out there now. I need to be taught about this, but for me, it was the kind of, I don't know, maybe in some ways, quite simplistic version of metal, but there was an awful lot of power in there and perhaps, psychologically speaking, I'm sure there are very many interesting points that a psychologist could go into as to why I was drawn to that, but it moved me. (laughs)

GG: Yeah! So you're mentioned Wasp: does that mean we're talking about what I would refer to as Hair Metal, that kind of Sunset Strip vibe, right?

JQ: Yeah, absolutely. Absolutely! And I mean, possibly, you know, the hedonism of it or I don't know… I'm still very, very fond of this music! And so when I hear Cinderella on the radio or I hear Ratt, for example - which occasionally does get played on Planet Rock even these days - then I'm really happy.

You know, Saxon! I remember being with my daughter when she was little in the kitchen, and we were dancing around to Wheels of Steel, you know, stuff like that. That's my bag! I mean, I have progressed a little further in my tastes, but not that much, Ray, to be honest with you! (laughs)

GG: It goes in both directions, though, you know, that way because it's like, um, it took me until about four weeks ago before I ever heard Painkiller by Judas Priest.

JQ: Oh my God!

"I think that the metal community as a whole, their tastes go beyond what convention says is or isn't metal. I think they are drawn to heaviness of intent"

GG: Right? haha! I was kind of like, I can't believe these guys are going so hard! That tune is particularly going for it! And I was like, this is not what, you know, Judas Priest was in my head! I wasn't sold that idea of Judas Priest in the slightest. I thought they were kind of like a weaker Iron Maiden. And I was like, holy shit!

JQ: Ohhh, no. (laughs)

GG: So yeah, I mean, it goes both ways! And when you're talking about hair metal, I think: you can't really argue with a great tune, can you? It doesn't really matter the context.

JQ: Yeah, precisely. I see it completely. Take it just for what it is put out there intended to be, and it's fun. Yeah.

GG: Exactly! So, you were playing cello. Am I right in saying that you took that into kind of, like, classical training and sort of like higher education? Did you study cello and so on?

JQ: Yeah, that's right. I did a performance degree in music. I studied with the CYM, as I told you, all the way through. And that included like the London School Symphony Orchestra and all this type of thing, wonderful opportunities and experiences.

And then I went to university and did my music degree, and at the time, what was available as a music degree, a performance degree, was very, very fine teaching but I personally wasn't in the right mindset and it wasn't quite right for me. The degrees and the education that's available now is much broader. In fact, I know this because I teach on a Master's course but at that time that wasn't really available.

So it was rather a case where I felt all the time a little bit like an outsider. I'd gone from this very kind of freeing, liberating kind of musical education into a university education, which was quite a sort of staid route. I wasn't mature enough to flag up that it wasn't right for me, so instead I used to do the bare minimum to get by. I spent a lot of time DJing Hair Metal nights, you know, in clubs and on radios as well. When it came to my final recital, there was a large question from the professors at the time as to whether I was a very natural cellist or not. And so I, you know, took their wisdom on board and stopped playing for seven years. I stopped playing.

(Photo: Simon Kallas)

GG: Oh, wow, that's crazy! Given that I've only known you to be this incredible virtuoso, that just seems like nonsense from the higher ups!

JQ: It's not their fault. It's just that the approach, I think from the classical side at the time, there was one way to be a professional cellist and only one way. And we know now, thanks to Tina Guo and to Zoe Keating and all the other people, of course, there's millions of ways of being a professional cellist. But at the time it was a little bit different.

And like I said, I wasn't. I wasn't very kind of…mature, I think?...as a person perhaps? I knew I loved music, but I didn't really know how I could combine what I loved - which was this other side of music and this metal side and hip hop and all sorts of other things that were going on as well - how could that come together with what I've been doing? At the time, I didn't see, I couldn't see maybe because there wasn't really very much… I mean, there were plenty of people playing cello in interesting ways, but there wasn't anything exactly that inspired me.

"Your own concept is the only limitation there is"

GG: Right, so there was this whole big seven year gap, and then something happened which you're just going to tell me right now (laughs) that brought you back and presumably started you on the path that was towards your From the Sea albums and onwards. But I'm jumping ahead! So you had these seven years in the desert - the temptation of Christ, as it were - and then you came back. So what was that? What was that moment for you then?

JQ: So, during those seven years, I had a job, you know: paid got paid, I worked in the city, and I had been playing synths and keyboards for some older friends of mine who had put a band together. I wasn't even playing piano at the time, and I just played a little bit of synth, you know, basic covers, band stuff.

Then, through connection of one of these wonderful steps of someone who knows someone who knows somebody, somebody said to me, “You used to play the cello, didn't you?” And I was like, “Oh, not really”. And they said, “Well, Rose McDowall of Strawberry Switchblade is looking for a cello for Whitby Goth Festival. She wants a cellist to play a set with her. Do you want to do it?” And I was like, “Oh my God!”, you know? I was terrified! I said - thank the gods - I said yes.

(Photo: Ake Tireland)

And it's so funny, Ray, because I remember this gig. I mean, now, you know, I've been blessed to have thousands of stages, but that was my first stage like that, playing my acoustic cello and playing for this iconic woman, you know, with her band. We were all sort of brought-in people. We've since all been very firm friends for all of the years following. And I was nervous as hell, I can't begin to tell you! But that was when I started again, and something - perhaps because I'd come to it from entirely the other side of the fence, you know, nobody had asked me to play the second cello in the Schubert Quintet or something - it'd come completely the other side.

There was also, crucially, I think, the aspect of improvisation, because there was no sheet music, obviously. So I've always been pretty quick at, um, doing things by ear. And in fact, I do a lot of that now in sessions and stuff, so that wasn't tricky to me. So learning these songs wasn't tricky, but the thought of performing them was, you know, that took some real…I had had a long walk to that stage, you know what I mean?

GG: I do.

JQ: Anyway, then and then it went off from there and I found that I enjoyed the experience. Then I found my new teacher - who I don't study with anymore - but at this time, he was a very, very inspiring teacher, a completely classical person but very sort of contemporary. So, we would look at Lutoslawski and stuff like that as well as, you know, heightened concertos and stuff. As we went further on. But in his book, there was no room for doubt. No room for doubt. It's a very, very, very powerful feeling to give someone. It's like: you're just going to do it, you're going to play it; off you go! And actually that is a very enriching attitude to have. So the path began there.

GG: Wow, that's so cool. Wow, he sounds amazing, that's really inspiring! So, let's jump to what you're kind of probably as well known for. Obviously, your cello playing is incredible, but it's the cello incorporating the loopers. And I'll come back to the loopers as part of the conversation as the conversation goes on, because I've got different angles I'd like to ask about. But I suppose what I'm really interested in to begin with is how you go about composing one of your own pieces. You've spoken a wee bit about how you're quick to pick up with your ear, like presumably relative harmonies and so on, and you're it doesn't need to be written down music. So I'm thinking, presumably you compose your cello music on the cello, right?

JQ: Sometimes: I'd say most of the time I do, but sometimes the ideas can come from the piano. Just noodling about. It’s why I think playing the piano is It's pretty useful thing to be able to do, just because it’s a very quick way of being able to hear your harmonic progressions, particularly if you’re not going down a conventional modal or diatonic route.

"I found a very, very inspiring teacher. In his book, there was no room for doubt. No room for doubt! It's a very, very powerful feeling to give someone"

But other than that, yes, composing on the cello: if the starting point isn’t something harmonic, it’ll be a textural thing because I do a lot of sound design that I build up with my BOSS GT-1000. I might create a sound and that will be the starting point for a piece too.

GG: Yeah, it’s as much about - I’m putting words in your mouth here, maybe you’ll agree with me - but the sonic qualities are the important factor and the means behind it and secondary to the sound, right?

JQ: Yes, I agree absolutely. You’ve summed it up beautifully (laughs).

GG: Haha, so with a composition, it’s not like Bob Dylan who might sit down with C, F & G and he has a message, which will be threaded in with his wordplay. With you, your songs are like journeys that have lots of different stops and lots of different moments. And of course, you’re still having to account for the limitations of the looper. But the actual composing process: do you have an initial idea and then work at it for hours? Or are you playing away and something suddenly suggests itself? Typically, how does that process reveal itself to you?

JQ: Well, if I could give you the typical answer then I’d be happy, but each of them are very, very different! One thing that does tend to happen is: I’ll give you an example of a nice piece I’m working on at the moment. The components are there: I’ve got a sound that it starts with, which is a very eerie sound that shouldn’t really work, but because there’s a chorus at the end of the sound, it kind of breaks. Then there’s a refrain that I intend to remain in the piece, but it’s not quite right at the moment because the frequencies are too wide, so I have to think about how I’m going to deal with that. Because of the looping, we have to be mindful of which frequencies are going where: we don’t want to end up having four loops in and then having a massive boom at 125 hz or something! You have to think vertically and horizontally!

Actually, Adderstone is a better example of this. So, I’d be playing the beginning of it over and over until eventually you kind of fly off at a tangent - accidentally, normally - and then the thing kind of opens out and the next bit of the path appears. It’s like a series of roundabouts.

With that sort of thing, obviously The Cartographer is more of a sort of long-form straight composition for many musicians, so that is different: that’s composed very much, because I don't’ have to play every single note in that piece, so when I’m writing it, scoring it, I’m thinking about where the trombones will come in, and who’s going to take that, blah blah blah! It’s a much easier thing to do.

Effects & Sound Design

GG: Yeah, yeah! So, would you say that sometimes things like hazard is a part of the invention as well? I don’t even want to say mistakes, because it’s just when you experiment with the cello - and you use the full scale length that’s available to you - then you have the extra things with the sonics, the effects…you’re gonna run into artefacts that you’re maybe not expecting. But those things: could they be compositional elements as much as notes?

JQ: 100%. Yeah, because they often become the DNA or the defining aspect of a piece. There’s a piece called Reya Pavan which begins with another very broken sound, and that kicks that entire piece off. What I did actually was I bowed by accident an open string on a setting which is normally one of my percussion settings. I found that when I bowed it instead, the GT100 - the model below the GT1000 - just couldn’t handle the sound. It kept going (makes glitching sound) and I thought, ‘that sounds amazing!’ Then I had to spend months making the GT-1000 behave in the same way because it’s a much more advanced pedal and it could handle this! I had to spend a lot of time making it act like it was broken in order to produce this sound!

GG: Yes! Let’s go down that road, because I’m really interested in this. Even when you said about one of your patches that is ‘for percussion’. Most people who’ll be reading this will be a guitarist or bassist, and for us it’s a matter of: clean, crunchy, distorted and effected. Percussion doesn’t even become a consideration! You’re using these devices and the developers weren’t even considering an artist like you using!

JQ: Yeah.

GG: It’s an incredible range of sounds. I’ve told you before that the big distorted cello sound you get is ultimately how I wish my guitar sounded (laughs), so let’s talk a little about sound design, and how you have your tool kit set up. Are you using things like amp models?

JQ: So, it depends. Let’s take the GT-1000, which BOSS gave me a while back. The first thing I do is build something that resembles a clean sound, as good a natural cello sound as I can get. Once that’s done, we’re okay, you know? When it comes to percussion, very often the EQs are peculiar. There’s a piece I play called Mandrel Cantus, and on cello I have an advantage in this instance of a curved bridge and curved fingerboard, and all of my pickups are in the bridge. Depending on where I hit the strings, if I damp them with the left hand and hit them, I’m going to get that sound that’s kind of like a palm mute.

With the percussion sounds, there’s always a compressor, there has to be. Quite often, I will make the reverbs do quite a lot of the work as well. For the Kodo-style drums at the start of White Salt Stag and things, I’ll cut a big chunk out of the high end but really boost the low end. In that instance, I’m using two amp models: a rectifier and possibly a concert bass amp, something like that. The EQ will usually be present or even boosted at 63 Hz and then there will be quite a significant scoop, then a little bit in at 1k and then again right at the top end as well. For live performances through a PA, where nuances of sound very often are lost, what we must do is present what we’re doing in primary colours, clearly defined things.

(Photo: Nick Hodgson)

So I do this very funny EQ and then when I hit the cello, I get this hit at the front of the note and then the resonance of the body of the ‘drum’, if you like, is taken care of by these other frequencies, and then whatever I choose to let through the reverbs.

Or, sometimes, the reverb will be at the very start, like with Cantus, where there’s a reverb and a delay right at the start of the chain, with no direct signal. If you watch it being performed, you can audibly hear that sound, but you won’t hear the beat until it does a crotchet note. That way, we get rid of the sharpness of the sound, but we let the ‘jjjooop’ through, do you know what I mean?

GG: Yeah, I do!

JQ: It’s pretty cool.

GG:It’s brilliant! There’s so much architecture involved and I love all that. Do you know what’s funny? You mentioned using a rectifier amp model, and the fact that you’re scooping the mids from the EQ: that’s proper Metallica guitar sound stuff, isn’t it? (laughs) You’re the James Hetfield of cellists!

JQ: Haha, yeah! It is, actually! The Metallica EQ.

Looping

GG: So now, you have the GT-1000 and the looper. Would I be right in saying that most of the time, the GT-1000 would be the first thing in the chain, before the looper?

JQ: Correct, that’s right.

GG: Okay, now the looper. For anyone listening to your music without seeing the performance either in person or on Youtube, they hear lots of cello and don’t have to consider the fact that it’s a single performance. The looper is integral to that of course. Is it the RC…600?

JQ: 600, yeah.

GG: Okay. How are you using what you’ve got in a general situation? You know how with a linear looper, however long the first loop in will dictate the length of all subsequent loops, so you have to think ahead? You don’t have that problem, do you?

JQ: No, I was really lucky: I was able to work with this pedal during the beta testing stage. So there’s loads of hidden videos on youtube of me sitting on my floor going ‘Hans, I can’t get it to do this, I can’t get it to do that!’ (laughs) So you can do basically…your own concept is the only limitation there is. You’ve got 6 channels on the RC-600 and you can set them to run straight down, that’s easy, no problem. You could have them running in free time with each of them being synchronised or you could set a bpm and bar lengths so that they will fold, like one is two bars, one is six bars.

What it’s less keen on - and what I had to find a workaround for - basically things when you can’t divide things by the loop evenly. Raya Pavan is a good example. It’s only using three of the channels, but one channel is one bar long, one is seven bars long and one is six bars long. What happens there is that the 6 and 7 bar channels have a tiny bit of material in each one - so most of the loop is empty - but you set them off and of course the returns come back on each other at changing times, and eventually there will become one moment where they’re beginning to cross and you’ve got other harmonic possibilities. This one moment, they’ll sit on top of each other and you’ve got this very dense chromatic harmony, and then they separate again as they go along.

(Photo: Simon Kallas)

This is personally how I try to get variety into a performance. I very often will use different bar lengths or the smallest component I can, like 2/4 with a very fast bpm: that way I can pretend I’m doing one beat at a time and set 17 bars of that, and then 14 bars on the next channel. It’s a way to create some diversity and some movement and some compositional structure into something if you’re doing it by yourself, but it’s always something that has to begin with a ‘thing’.

On that artistic tangent, I use an input effect - you have an option for input effect or track effect - so the input effect I use on every single one is a dynamic compressor that is set to zero, it’s just turned on. What I find is that it just brings a little bit of clarity to the sound for front-of-house purposes. The track effects, that’ll be where I set the effects to be either coming from the right channel or the left channel, and on the Loop Station, there’s a point in Forge where I kick on that pedal and about ten different things happen, including: setting the panning levels differently, putting an amp simulator on one of the tracks, and so there's a lot of options. It’s crazy, Ray!

GG: And people don’t understand that part: your audience are loving it, but they’re seeing you playing, they’re not comprehending that there’s a whole universe of tap-dancing and forward thinking going on too! Now there were a couple of points I wanted to get back to there. You mentioned about the different loops having different numbers of bars, and the loops meeting and causing unusual note clusters: was that an example of you wanting that particular effect and you found out how to do it, or it happened and you thought: ‘that’s amazing, I’ll use that’?

JQ: It’s a combination, actually. As a compositional tool, that's verging into Surrealism with the repeated bars and the effect of that: that’s something that the classical world has been fascinated by for a long time. So there’s nothing new there, but it’s a very useful tool if you have something like the Loop Station, which is a pretty advanced yet basic method of doing things!

"One of the all-time fabulous achievements of mankind was to create instruments that we can put our creative being into and maybe become better people because of it"

I’ve used this technique for a long time, but it would’ve been in a very infantile stage for a long time. But you’ve only got to go a couple of steps ahead before you start thinking of harmonic structure. That last example, Raya Pevan, the basic melody is in C, and I miss out 3rds when I can, because if you put a third in, you are committed. This one starts with an open 4th, and then we do have a minor 3rd, and that’s all on one loop. The second loop has a slightly higher 4th that slides up to the 3rd and back to the C and G. In my mind, I knew at one point we would have a very firm sound that would sit on a C very nicely, but beyond that, it starts to go into A flat. If the third is in, I don’t care about major or minor notes together, I do that all the time. But having this harmonic structure in mind, it’s difficult to foresee that, so you can only know this if you try it out, and then you say ‘Ok, I like it!’ You have to test them out in real time, so it’s trial and error. But I sketched out on manuscript paper what was happening each time, and then I wrote the theme on the top of that, because I knew what I was writing to, you know what I mean?

GG: Yeah! That’s incredible! I see how it’s both premeditated and kind of hazardous, for sure! See when it comes to choosing notes, I’m thinking of the Modes here really: do you have like a…I think the word I want is ‘opinion’; as a composer, do you have an opinion on the Modes? In relation to the cello, do you have a preferred Mode or Modes to reach for, maybe for triggering certain emotions? I find your musical often sounds quite romantic, but often still quite exotic and unusual. Do you have ‘modal’ places you go to in order to get those things?

JQ: No, I don’t. It’s very interesting, because we have quite a lot of discussions about this actually at uni with students.. I’m not a fan of defining music by the mode. Unless we’re dealing with actual modal folk music or something, in which case, yes; or if we are dealing with a particular music which is archetypal of an area, then we can probably say that certain things are modal and that’s what is commonly used. But beyond that, music moves in and out of modes. I mean, quite often I will use a flat 2nd, for example. That’s like the beginning of the Phrygian mode, but I also use the minor and major thirds together and I use all sorts of other things as well, so for me, it’s more like scalic decisions I’m making. Or I’d employ a series of notes that I want to use and only those notes, rather than being concerned that ‘this is definitely Lydian’ or whatever.

But with the cello, we’re tuned in fifths, so I think we’re kind of drawn to major or minor - natural minor, harmonic minor or whatever - it doesn’t matter to us because we’re in fifths and that’s a barre chord, effectively! (laughs)

Touring with Doom Bands & Gratitude to the Metal Community

GG: That’s really interesting! I just wanted your take on that, thanks! So: touring. Most of the time, if not all of the times that I’ve seen you perform, it’s with quite niche metal, doom or metal-adjacent bands like Boris, Amen Ra and also Heilung and Myrkur. I wondered, after we hear your music and understand the context of it, it makes sense for you to be on these tours, but are you ever surprised that the audience and communities for these bands are as receptive to a lone figure with a cello when they came out to see a band that’s massively heavy? Is that not unusual?

JQ: I don’t know, Ray! I’m always very humbled and thankful and empowered by the reception I get. The conclusion I draw from these types of receptions is the fact that people into this side of music are very, very broad-minded. I think that the metal community as a whole, their tastes go beyond what convention says is or is not metal. I think they are drawn to a heaviness of intent.

Amelie (Bruun, from Myrkur) is a good example because she is doing her metal thing, and then off she goes and does her folk thing but that was heavy as hell as well. The Bach C minor Cello Suite is heavy: my god that’s heavy! And one of the most heavy is probably the Sarabande!

GG: True.

JQ: It’s so slow, it aches! It pins you back in your chair when you hear it - and when you play it as well! So I think, more than anything, it’s a huge shout out to the metal community for being broad minded and willing to give something a go. I can’t think that that would necessarily be the case with any other genre of music. I certainly cannot see a traditionally classical audience welcoming a band in a way that a traditionally metal audience have welcomed a soloist. I could be wrong, Ray, I don’t know.

(Photo: Simon Kallas)

GG: I think you’re totally right.

JQ: I’m just thankful to them. Really, really bloody thankful! I think about Hellfest: that was the biggest one for me. I was on the temple stage thinking ‘WTF’, as one does (laughs) and that audience: my god! What an audience! And I was sandwiched between Cradle of Filth and Combichrist, and it worked! Perhaps what I do serves to make the heavy stuff heavier?

GG: Maybe?

JQ: Juxtaposition is everything in music! Light and shade. I dunno.

GG: Absolutely. You do also manage to make your cello sound like a huge distorted guitar as well! That can’t hurt! Nobody expects it and when they see and hear it happening, they go ‘Wow, that’s awesome! She DOES speak our language! Pay attention!’ After the fact, it makes a lot of sense, but prior to it, I just wondered how you felt about it as the person who was going on stage. But, as you say, they’ve accepted you, which is brilliant.

JQ: I know what you mean. Bear in mind I never had a traditional kind of…it’s not like I was performing the Elgar Cello Concerto and then woke up one morning and thought: ‘Do you know what? I’m gonna do something else!’ So I never had a conventional stage.

GG: Of course. Now, performing alone as a solo artist. Is that something that you particularly prefer over ensemble and group work?

JQ: It depends. It’s easier to incorporate what I do with an orchestra, because I’d have a conductor. On The Cartographer, the conductor was connected to my click track. The only issue was that beat one had to be one: there was no deviation otherwise the whole thing would fall apart! So it was a bit riding by the seat of your pants. It’s easier for me to perform with my loops and everything else on my own. It’s also easier for touring and I don’t have to have a row with myself! (laughs)

I like to stop by and be a part of someone else’s ensemble, that’s a lot of fun. I’m happy with whatever is presented, but I will probably think carefully before doing a band version of my tracks, because it would be an enormous amount of work. I mean, it depends on who’s asking, really! But I’m not adverse to the idea, but I can tell you now: if I’m 100% in control, and therefore responsible, it’s just easier for me.

Practice

GG: Most certainly. Now, Jo, I’m not trying to embarrass you with flattery, but you are quite a fantastic player. How much time do you have to spend practising to stay at the level you’re at, compared with say, a few years into being proficient?

JQ: I practise more now than I ever did before. So when I did my degree and everything else, I didn’t practise very much at all. Now, I practise every day but it’s because I want to. I’ve noticed this really weird thing, which is that if you practise, you improve! It’s taken me 40-odd years to figure that one out! (laughs) You know, there was a wonderful quote, I think it was the cellist Janos Starker, and they asked him in the nineties, ‘Maestro, why do you practise, still?’ and he said ‘Because every day I feel I’m improving!’

The journey of an instrument takes twice as long each time, to get half as far. But: we’re not doing it for that. We’re doing it because we have to. It’s a compulsion; it’s part of our soul. It doesn’t matter what our instrument is, it’s the greatest joy, and to be able to sit, focus and play like that is, I think, the greatest privilege. One of the all-time fabulous achievements of mankind was to create instruments - and we have voices too - but we have these instruments: my god, you know? Thank you Strat, thank you Guarneri, thank you Gibson (laughs), because here are these instruments that we can put our creative being into and we learn to maybe become better people because of it.

(Photo: Simon Kallas)

Being In the Moment

GG: Wow, now that was a fantastic statement there! One of the things that I’ve witnessed at every one of your performances is that you always seem ‘in the moment’ as a performer; very present. I wonder first of all if you would agree with that statement, and then; do you do certain things - practices or whatever- that help you prepare yourself for the stage, so that you’re like that?

JQ: Yeah, I agree with you. It’s a really weird thing, being on stage. I’ve got a theory that time doesn’t operate the way we’re all told it does, anyway. On a stage, time runs at two different speeds. It runs extraordinarily fast, and at the same time at a snail’s pace. I quite often get lost and caught up in that concept when I play because I’m not thinking about the real time of what I’m doing - this loop goes on, that loop goes on - because if I start to think about all that, I lose everything. But at the same time, I’m wholly aware of everything. I can’t really describe it.

But in terms of preparing for the stage, I always take my time before I go on to the stage to be alone. If you come to a concert, 5 minutes before I go on, I will be there at the side of the stage and I’ll be in the dark! Luckily, stage crews seem to be used to this sort of thing. But I’m just thinking. Visualisation is quite important and I just visualise playing, and I breathe - because we don’t breathe very well sometimes, when we play - so I do a lot of that. I do a lot of physical stuff anyway, because I like to feel strong, or as strong as I can be! When it comes to the stage, there’s just this space beforehand and then, as I walk to the stage, it’s almost like you uncurl out of yourself and everything lifts, and then you walk to the stage. In that walk, from side of stage to stage, I settle into what I’m gonna do for that next half hour, hour, twenty minutes, whatever.

Then, it’s those two separate times running, and then…I have a glass of wine. (laughs)

Co-Headline Tour with Jon Gomm

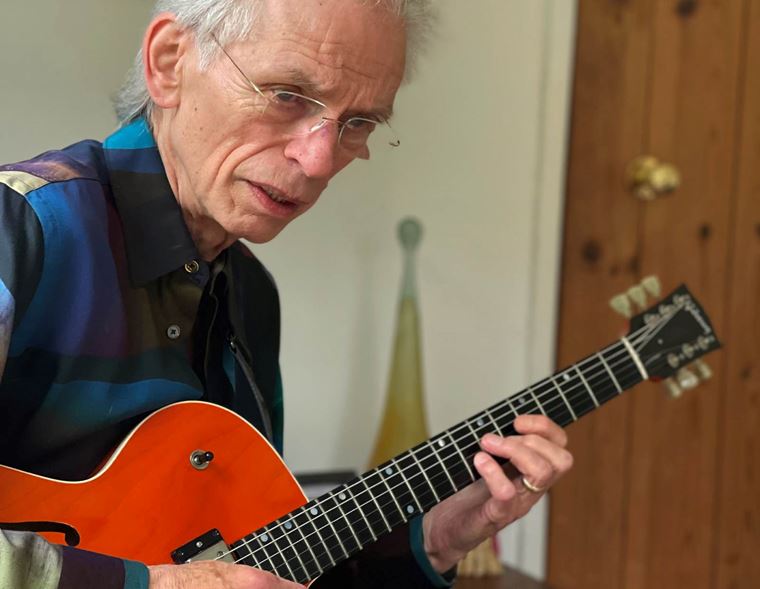

GG: Excellent! Haha! That’s really interesting. Now, just before we say goodbye today, you’re just about to embark on a co-headlining tour with Jon Gomm. Jon’s somebody our readers will be familiar with, and indeed I’ve chatted to him a few times too. That’s a great idea, this tour: was it the looping thing that kinda provided a conceptual link between you two?

JQ: Well, the tour is called the parallel worlds tour and I think that was the kind of main idea behind it. We’ve both got the same booking agent and he thought that it would be an interesting concept because it’s two musicians doing pretty technical and pretty intricate things with very different outcomes. It’s gonna be so much fun. We met up a couple of weeks ago and we got on like a house on fire, and I’ve got so much respect for his virtuosity. His song-crafting as well and his performance: everything about what he does I find very inspiring. I’m hoping that I will do justice to my half of the gig as well, but I reckon it’ll be interesting for audiences who are into either him or me, to see the other side of the fence.

We both do weird things with our instruments (laughs), to sum it up!

JacQue.jpg)

(Photo: JacQue)

GG: Do you reckon there might be any potential for you guys to perform together?

JQ: Yes. Yeah, absolutely. Whether he likes it or not (laughs). I think what would be lovely is if we do a crossover in the middle, because it's a co-headline tour, so fine. I don’t mind how we do it, but I do not like rehearsing, I really don’t like it, but I would 100% get on stage with someone I’ve never met before and perform like that with that, rather than be shed building in a studio for days on end.

So for Jon, this is exciting because he can play all of his wonderful stuff and maybe I’m the one who does the canvases of weirdness, for him to float his glorious stuff on top of. I don’t know, let’s see! Whatever we do, it’s gonna be different every night.

Jo Quail and Jon Gomm’s co-headlining tour starts very soon and continues into 2024. Head over to the official Jo Quail website for tickets, music, videos and more.

I’d like to thank Jo for her time and candour. What an inspiration!

For more exclusive interviews, do head on across to the guitarguitar interviews page, where you’ll find exclusives with everyone from Sophie Lloyd to Steve Vai!