"The subtext to music is to re-energise and to heal: it's very powerful medicine" Steve Hackett speaks EXCLUSIVELY to guitarguitar!

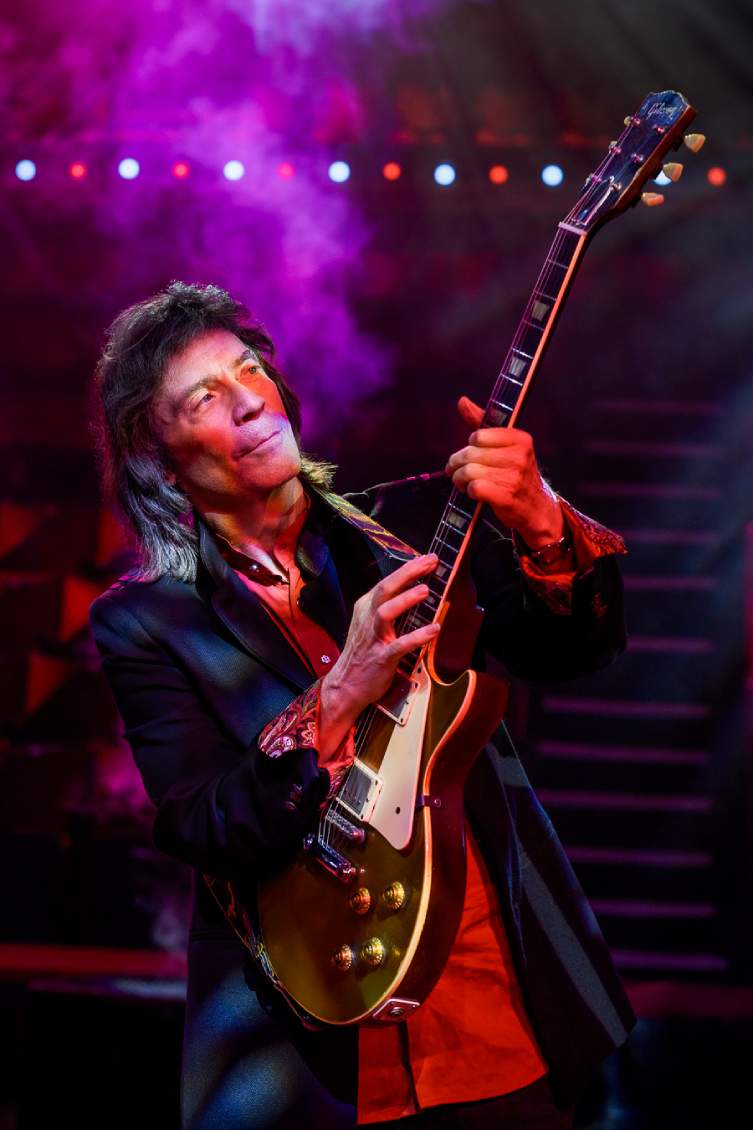

I’ve been lucky enough to chat to Steve Hackett a number of times now. The ex-Genesis guitar legend has created an artful body of work over the years that is as ambitious as it is colourful, and whilst he definitely has a signature style, we still never quite know what’s coming next.

Indeed, one of my chats with Steve was entirely based around his epic nylon-string guitar album, Under a Mediterranean Sky, whilst another focused on his highly readable autobiography, A Genesis in My Bed (there’s a story behind the title!).

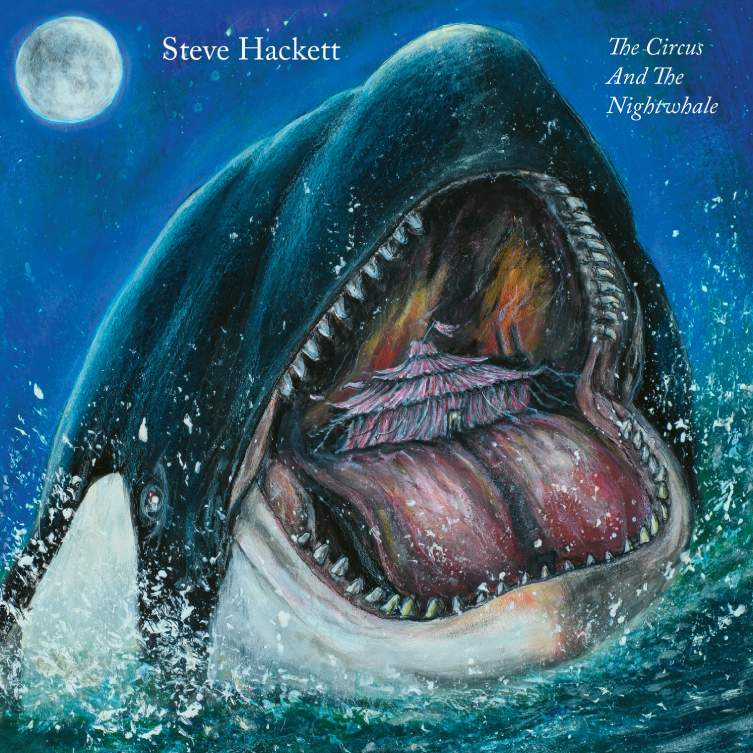

This occasion was to discuss his new album, The Circus and the Night Whale, his 30th solo record and one that has seen him enjoying possibly the best reviews of his career. He recently appeared on the cover of Prog magazine, and is embarking on multiple international and UK tours this year.

Things are going well for him! As they should, too. Whilst revered in guitar circles, it’s perhaps fair to suggest that Hackett is something of an underrated musician and writer: a national treasure who deserves to be a household name. Still, his musical adventures remain vital and kaleidoscopic, filled with lush instrumentation, searing guitar playing and a sense of wonder about the world that adds a sprinkle of magic to his compositions.

As ever, Steve is a delight to talk to: charming, friendly and happy to dive into a myriad of off-topic transgressions that only serve to enhance the conversation further. In the past, we’ve touched on some fairly esoteric subjects, and those curiosities continue in today’s conversation, which is transcribed in full below.

Steve talks about the new record’s themes, its genesis (excuse the pun), the writing and the recording. He talks about Genesis, guitars and the healing power of music. It’s all here folks, so roll up and join the circus…

Contents

The Circus and the Night Whale

Life, Death and the Multiverse

Risks, Sgt Pepper & the Power of Brevity

(photo: Tina Korhonen)

The Circus and the Night Whale

Guitarguitar: Well, this will be our fourth time talking together but the first time we've ever actually had a face to face, so it's nice to get a proper conversation! So, the new record is absolutely brilliant! I've been listening to it since I got a copy. I’d love to start by talking about the concept behind it. I know there's a character involved that's called Travlah, which is a loose version of yourself. Is it like a tight narrative or is it more of a loose concept in terms of the record?

Steve Hackett: Well, there is a tight narrative. It's autobiographical but there are certain things that my wife and I wanted to achieve that meant that we could only really do it metaphorically, so we came up with the idea of a third person. It's a bit of a stretch to imagine that it starts in the first person then becomes the third person,

But John Lennon never had any problem with that with I Am the Walrus, So I don't see why I should worry about it! (laughs) I'm glad you like the album. It seems to be the best received of anything I've ever done so far! And you know what? I cannot work out why. Because whatever you do, you invest with a similar amount of hopes and all the rest, but it just seems to have caught the imagination.

It's probably got something to do with the way the album starts, which has got nothing to do with me, but just an edit, or a fly on the wall of an imaginary documentary starting literally in 1950 when I was born, and an example of what radio sounded like. Or a few short examples of that. So I think those false starts that lead you into it, that step through the patronising tones of the BBC, circa 1950, (laughs) being followed by a very uncomfortable baby listening to mother, which then gives way to an incoming steam train. When that's up to full speed, it dictates or conducts the incoming string orchestra with Big Ben, which sets the pace in turn for the rock band that follows.

So maybe that's the most important moment of the entire album, what happens in the first minute or so, I suspect.

GG: Hmm, yeah! A lot of that is interesting, particularly about the timing because I feel like the album is quite concise, given how dense with ideas it is. So I'm wondering, with the concept of it: I mean, I don't know how your practice normally is in terms of whether you collect songs and then there's maybe a thematic thread through them that you might tie together? Did you have a concept in mind prior to the material this time?

SH: Well, I started off doing a love song that was also a rock song - that's also a contradiction - about Jo, and that was the track Wherever You Are, the penultimate track. That was the first thing to be recorded. Then Jo and I started to talk about where we could put that song: originally I was thinking, well maybe it could be at the beginning, but I know that she had reservations about Proggers struggling with romance (laughs), therefore, that was a hard thing. I played it to a few people, they seemed to like it. By the time we got to the second track, the Get Me Out track, that referred to my time in Genesis, being thrilled at first and then wanting to get the hell out!

The concept really started with the second song, Get Me Out: the idea of the biographical nature of it, autobiographical and all the rest. So, we started to piece it together from then on. It wasn't as if all the songs were written and we found up a loose concept. It wasn't. It was very much tailor-made, like self-commissioning. Well, between the two of us really and then there's Roger's input as well as these things were being recorded. We got everything down on paper as much as we could. So lyrical input from Jo, lyrical input from me.

Yeah, the idea was really born between the two of us and then, to bring it into reality, Roger King was on board and he was recording it, playing keyboards, programming and coordinating. We had some of the performances collected when I was on tour: we were recording in halls as we were touring. We were doing a lot of touring and that meant that we would be a little bit ahead of the game by the time it came to coordinating at HQ which is in Teddington, here. That was important to be ahead of the game. The rest of it is, it's a complete surprise that any of it works at all, frankly. I'm always amazed when we come to the end of a song and you think, yep, that's ready! Because they go through quite a lot of changes, particularly when I'm doing vocals.

I'm a bugger for going back and re- doing vocals, working and reworking using all the technology available to assist them, and then some! I think the biggest challenge is probably that, but I've been employing myself as a singer now for quite some time. Eventually you have to admit that that's what you do. I don't put it on the passport: ‘what are you?’ ‘Singer’. No, I don't do that. (laughs) I don't put ‘guitarist’, I put ‘musician’! But there we are.

Life, Death and the Multiverse

GG: One of the things that I always have noticed about your solo material is the juxtaposition of some pretty disparate types of style or metre or feel: it's very colourful music to me and so that led me to two questions, so I may as well ask you them both in the same time!

One of them was: do you tend to see music visually in terms of painting a picture or a series of pictures? And then the second part is: the juxtaposition I was thinking of comes at the end of Get Me Out that then segues on to those lovely celestial choral backing vocals of the Ghost Moon song. I thought, I'm getting a real dynamic journey, kind of like how I'd feel if I went to the circus - and I understand that the circus is a metaphor for Genesis sometimes in the record - but are you also trying to evoke that kind of like ‘you don't know what's coming next’ feel of a circus? That sort of rollercoaster of thrills vibe?

SH: Well, I think the circus, certainly, joining the circus that was Genesis at the beginning of the 1970s: that's true, but I think of the circus as very much the whole of the music business. It all functions in that way: my life within it, a touring musician, living out of the suitcase.

That's it, you know, where everything is primed and you try to conserve your energy as much as possible for the night's performance, but inevitably getting to somewhere has an effect on you. So yes, it's part circus, isn't it? All of that.

"I think that life is pretty much a hero's journey, a hero's quest for all of us"

But then beyond that, the Night Whale was really at the point when I very nearly had a nervous breakdown. It was way beyond Genesis, at a much later point in my career where I was being controlled and it was literally preventing me from doing live shows. I desperately wanted to be able to get out there and do it again. But at one point I was in a hotel avoiding people and I was literally on the bed shaking, and I thought ‘this is a nervous breakdown, but it doesn't mean to say you have to tell anybody'. You just keep quiet about it until you get yourself under control and then with any luck, all will become clear.

I was entertaining suicidal thoughts at one point, which shouldn't really have happened but that was me not knowing whether I was coming or going and once I realised that I needed to have Jo full-time in my life, because I started to care more about her than about me. Am I painting a picture here to fill in the gaps? Once I made that commitment - that leap of faith - life started to change and we were able to function as a full-time couple and face whatever it needed to be done. But the Night Whale was an image that she came up with. The idea of the lowest ebb; facing your demons. You can call it the Dark Night of the Soul. I suspect there's several dark nights of the soul that we have to go through, you know.

Neither of us have died yet, we haven't had to deal with that yet! But yes, I think that life is pretty much a hero's journey, a hero's quest for all of us, because we all have to deal with our own eventual demise. I think it's about whatever you make of life in between, of course. I remember hearing something that Ronny Lang said, the psychiatrist, shaker and mover in the 60s, he said: seen one way, life is a terminal disease with 100% fatality. (laughs)

And I think he was saying that after a few drinks, but it's absolutely right! I think he was bang on when he was sober and sometimes bang on when he was less than sober.

GG: That's a kind of negative spin of it, like you're never gonna get rid of this disease of life. I find a lot of the opposite in your music. I mean you just spoke to me about some really heavy stuff, and of course you extrapolate in that in your autobiography which we spoke about before, but what I get overwhelmingly from your music is optimism and joy and hope, and I think that's a pretty important message that isn't necessarily automatic for rock bands to do.

SH: Yes.

GG: Along with that, magic and colour and imagination. So I wondered if it's important for you to take - I'm gonna say your audience, but I suppose you're taking yourself as well - to a journey elsewhere, using metaphors and these stories to bring us out of this and into somewhere else?

SH: Well, funnily enough, I remember having this conversation with Peter Gabriel probably about two years ago, where we were both saying we felt that there was something else beyond this mortal coil, but not knowing what it is: in my case, having had evidence to support continued life. And I agree with you: I mean, Wherever You Are, that track really points to the idea of the possibility of continued existence and continued love. Having found your earth partner, would she be your partner in another dimension beyond this? I was talking to a friend recently who just lost his second partner, having gone through that dark door and he was saying that he thought that this world was actually a rehearsal for the next. Now, my mother would disagree and say this isn't a rehearsal, this is life, but I think that maybe he was onto something there. By the time we shape ourselves with enough - hopefully - compassion and start to realise the wider picture that goes beyond whatever the desires and needs are of the individual, perhaps the distinction between the tribe and yourself becomes blurred. Perhaps you will be able to serve hopefully a hive mind without feeling you'd actually lost anything, but that you gained something.

"I think the subtext to music is to re-energise and to heal people. That's why they listen to music: it's very powerful medicine"

GG: That's interesting! I wonder: I'm just actually but it's completely spitballing here since we're on that subject, but I wonder , would you subscribe to the idea that there might actually be multiple dimensionalities? So perhaps your friend, who has lost two wives: when he passes on, there could be two identical versions of him that might be simultaneously living with those separate people and kind of progressing his life in that manner?

SH: I don't know. The multiverse theory is an interesting one. It is entirely possible. You have to do away with the idea of singularities and addressed pluralities. Perhaps we are less singular than we think. I know that Jo often talks about this, about when her father was dying, and they were very, very close, he said: “I feel as though I'm in two places at once”, just shortly before he died. They had a series of very interesting conversations about that very subject. It's an intriguing one.

Multiverses, we don't know: we don't know what we're capable of. We don't really know the true meaning of existence. We are experts on ourselves and the environment in which we inhabit or float, in which we try to survive. But beyond that, all is conjecture. If I could change the subject slightly, I think that the subtext of music - and if I’ve said this before, I do apologise - but I think the subtext of music is to re-energise and to heal people. That's why they listen to music. It's very powerful medicine. There are some very powerful healers around. I've seen the effect that music can have on people who were basically devastated physically, but nourished spiritually through music and in some cases cured. I was thinking of - specifically - the work of Dr. Oliver Sacks, who was talking about Akanezia, the inability to move. Parkinsonian, if that's the right word. One of his patients he described as a woman who, when she was frozen, couldn't move. She was only able to move when she heard music that would move emotionally, then she was able to move. So, there's an example of music as medicine, and obviously absolutely crucial, critical, priceless to her.

(photo: Tina Korhonen)

GG: That’s pretty incredible. That's an amazing thing, but it's such a tricky one when we're dealing with things like this: you can go into things like, cymatics where literal frequencies are being talked about as being able to shrink tumours and move objects around. Even as musicians, we don't actually quite understand that lightning rod that we've got when we just put out a frequency: it can move people in ways that we actually don't have over, don't you think?

SH: Yes, yes I do. I think the most famous healer in the country was a guy called Harry Edwards who was talking about absent healing as much as heaving a patient that might be in front of him. I was intrigued by that, and occasionally practising that and having it done upon me, was hugely interesting. He was talking about people who had tumours. Funnily enough, I have a friend at the moment who has a tumour and we've tried some healing on him, but Harry Edwards said that when we’re asking for help from spiritual agencies with tumours, one should ask for dispersal. The word was ‘dispersal’.

So this was the thing to concentrate on. I've only had short-term success with healing with people. But I believe in it absolutely, implicitly. There have been times when I've had certain things that wouldn't go away, except by visiting a healer. It happened three times in succession for me, things that wouldn't go away and went immediately. I thought, my God, this is the most powerful form of medicine, so I got interested, reading Harry Edwards books and found that I was led to myself.

First of all with Jo, my wife. And it was also involved with music, quite by chance. But we had an interesting experience when she had tinnitus from a particularly loud rehearsal that I had and it wouldn't go away. I had my hands close to her, maybe about an inch away, and about 10 minutes into the healing, we both heard this enormously loud noise, this crack, and I saw a blue flash and she said it stopped. We were both in sync, we both heard this loud noise, and we knew it worked. And since then, whenever I've mentioned the story to people, they've talked about, you know, many friends have tinnitus and I've had some success in helping them.

Whether it remains short term or long term, I don't know. But literally when we were in Norway a few days ago, a guy who had done some healing on me and helped some osteoarthritis that I had in one hand. I think he'd managed to get rid of the pain I had, but he said that I'd managed to get rid of his tinnitus, which he'd had for years. So, hey! We'll see, you know.

GG: Wow, that's absolutely incredible.

SH: Yeah, weird, isn’t it?

GG: I'll look into that. The crack and the blue flash, that's not an everyday occurrence, is it?

SH: It's not an everyday occurrence, and it's absolutely real, and we both heard it, you know, a loud noise. It was loud, believe me.

GG: Wow. I could actually talk to you about this kind of stuff all day long, but I do realise I'm gonna have to move it back to the music, I hope that’s okay?

SH: Yes, it's probably got less to do with guitars, but maybe it's in the widest sense of the world, the effect that this beautiful thing allied music has upon us!

GG: Exactly, exactly. And actually, the previous interviews that we've had together, the ones we've gone off on those tangents have actually proved to be really resonant with the audience, so it’s valid.

SH: Oh, good!

Risks, Sgt Pepper & the Power of Brevity

GG: Absolutely. When I first started listening to the record, and before I understood that you were talking about it in somewhat autobiographical terms, I still was thinking back to our conversation about your autobiography, when you were talking about going to the circus in London as a kid. I thought to myself: is that coming through on this record? And, and added to that, when you mentioned John Lennon earlier, I've just been on a recent kind of thought process with Sgt Peppers and the nostalgia involved with somebody looking back at a kind of carefree element of their life and bringing that through.

And I wonder whether that's as important to the journey. Like, is that really maybe why you started, at that section at the start of the album?

SH: Well, I think that Lennon and McCartney, in my mind, are forever synonymous with Sgt Pepper, which they'd taken a risk on when they first did that album. They weren't at all sure whether the public were ready for it. But I think their risk was rewarded, of course, because it seems to be the album that defines the 1960s more than any other. You can analyse why all those character portraits - either quite literally on the cover or portraits in song - but they were so brilliant at it.

I thought it was the beginning of Sergeant Pepper, you know, the hushed expectancy of the crowd, murmur, the orchestra tuning up, and then the rock band: so wrong footed from the word go, but brilliantly conceived. I realised that that had been done, but that maybe I could come up with an equivalent with snippets of the BBC, the patronising tones thereof, examples of British radio, a little snippet, a soupcon of a used broadcast of Ollie Dell, both Pathé News things.

So, in other words, an album that started in 1950, in literal terms, all those things are from radio from 1950. That's it. So there's none of me at the beginning. I don't kick in until the rock band kicks in really. I think it's the nearest thing, my equivalent of an atmospheric start that might deliberately wrong-foot you at the beginning, but you get the idea that you would perhaps get some of those elements within the album, but it was a sort of compressed fragment or a taster of what was to come.

I tried to keep it up through the album. What was concerning me was the bar having been set by the Beatles. That was interesting. To do an album that was equally pan-genre as their approach became; to involve musicians from everywhere, if there was time - and I didn't have a lot of time to record, I was recording a lot when I was on tour in halls and at soundchecks - but beyond that, it's difficult to describe the process.

(photo: Tina Korhonen)

I was aware that having worked with my pal Brian May, we did some things at one point. I think, you know, those things escaped eventually years after they were done and I do believe they're going to be re-released at some point. It has Bonnie Tyler on it, Chris Thompson, there's an interesting team on it. Some of the Marillion guys were on it. But something I noticed about having conversations with Brian was that many of those extraordinary guitar solos of his, and guitar interjections, were quite short. I had the feeling that nothing really outstayed its welcome with Queen songs, it always moved on.

You would get a bit of solo vocal, you would immediately get a choir, you would get guitar effects back and forth, but nothing really outstayed its welcome. So, the idea of brevity. And by the time I'd done this album, I thought it was actually much longer than it was, but because I'd tried to keep up the pace so much, as in the introduction, it was very much shorter than any of us had expected. But I realised that when it came in at 45 minutes, we'd done the perfect length album for vinyl. The artwork is a perfect example of what works on vinyl. You've just got to see the whale's mouth swallowing the circus tent on vinyl for it to have the kind of effect that it needs to have. It'll only be big on vinyl or on some larger screen.

"I've been employing myself as a singer now for quite some time. Eventually, you have to admit that that's what you do. I don't put it on my passport!"

I guess that's, you know, some of the clues of what was motivating it with me. And I'm quite happy to say, okay, in progressive terms, 45 minutes is really quite short, and most of the albums I've done are closer to the 50 minutes, 55 minutes, an hour, sometimes even longer, special editions. But I thought, you know, this was the right length to tell that story. Sorry if it seems to be in brief, but I didn't want it to be a tedious visit. And again, if you look at those classic vinyl albums where we were being advised that the perfect length for a vinyl side at one point was 18 minutes in order to get maximum bass depth within the grooves, that was something that Genesis ignored greatly. But then that's because we had many moments of acoustic music, most notably with Selling England by the Pound, where Side two of course featured quite a lot of 12-string stuff that went on quite a bit in the Cinema Show, that sort of stuff.

Acoustic moments really defined Genesis, or defined early Genesis, I think. Those moments of stretching out. Something that I think might help, and predecessor in Genesis, Anthony Phillips really pioneered: the sound of massed 12 strings. I saw him just a couple of days ago, had a very nice evening with him as well as some other pals and I think he perhaps doesn't realise how brilliant his contribution was to Genesis, but when he told me about the songs that he wrote on Trespass for instance, I said to him with my hand on my heart, ‘well, I think those are the best songs on the album’. I thought the best songs were The Visions of Angels, Dusk and The Knife, and they're very different from each other.

GG: Yeah, that's very true and there's space for it all! Now, before we move on to guitars, Steve, I wouldn't say that your record is brief in the slightest: I think you've managed to tell quite a long, involved story. It's maybe concise, but here's something for you: whenever I listen to maybe Wolflight or The Night Siren or something, I tend to put it on and see it through and enjoy it, and then go and listen to something else. Whereas with this one, I've gotten to the end of it and just put it back on again.I wonder if that slight brevity has actually given it more of an addictive quality?

SH: Perhaps, yeah! I mean, it was something that Roger King had said for many years. He felt that a briefer album would be desirable, and perhaps even had that been applied to Genesis around about the time of Lamb Lies Down on Broadway, I think most of us feel that it might have made a better album if it had been shorter. Now, for its adherents and its fans, obviously that might seem like sacrilege, but that's what the team felt from within.

But at the time, you're off on that journey and you're doing it, and you're practically arm wrestling each other into submission. (laughs) You've got to go with the flow and so yeah, Roger, rather annoyingly, has been right.

Sometimes when I'm doing an acoustic thing, I think, well, it'll just have to take as long as it's going to take, know, we've got some acoustic stuff, we've got some orchestral stuff, things have got to be developed thematically, but they might even be rather longer than most symphonies or concertos, which are kind of over in a flash because no one was thinking about albums when when Bach was doing the Italian Concerto for Harpsichord: it was just the side of one side of a vinyl album and I've never sat down and timed it, but of course it's spectacular music and lovely and wonderful, so it sort of changed my idea of what it is I need to deliver to an audience.

And of course, there is the argument of saying: perhaps we don't need music by the yard, perhaps what we need is actually quality over quantity, and perhaps that idea of wanting to revisit the place, or places that the album had touched. I think that's a very good thing, and I'm pleased that you were intrigued enough to want to go back over what you'd heard and take it on board again.

(photo: Tina Korhonen)

Guitars

GG: Yes, very much the case! Now, Just a couple of guitar questions, of course, before our time’s up! Yeah, I always love your lead guitar playing and from speaking to you before, I understand about your fingerstyle methods and the tapping. There are some parts in this record where you're going unbelievably quickly and I'm wondering if you've done anything to change your technique, even though I know you've been a fast player? Are you using a plectrum at all or is that all still fingerstyle?

SH: I believe there are no plectrums involved. If I did use plectrum it may have been on the 12-string but just to give the sound of the strummy thing ringing out. I probably used a nail but we might have on the track Into the Ring, which is very Genesis-like with its 12-string and bass pedals driving it.

I'm not usually a great exponent of rhythm guitar even though I admire it greatly in others. It's probably Probably, yeah, the plectrum doesn't come into it. There's a fair amount of tapping, I'm sort of using two fingers to tap on the right hand at some points. I've discovered there are different ways of tapping. Originally, when I started using that technique, I was using the nail to hammer on and hammer off, the nail on the forefinger of the right hand. I discovered over time that most people use the pad of the finger, but what I discovered is that it produces a different tone using the pad or using the nail.

And there's another way of tapping, which is to use a ring as well. The ring I had for decades got stolen when I was away on tour in Argentina and I got another ring. When I was in Istanbul, I got a Turkish ring and that again makes a slightly different sound when I'm tapping with it. It's quite interesting. It's a sort of multi-faceted surface on it and it does some very good dive bombs, and it scoots down the strings very interestingly. You can sometimes use the ring to tap and incorporate a bend from the ring as well and I don't know if that's a technique that I've used on this album but I'll get into it in future!

I was also aware of the passing of the late, great Jeff Beck, who I met a couple of times. I was very saddened at his death, because he just seemed to be coming up with great stuff throughout the course of his career, always doing something surprising on this mechanical beast we call the electric guitar. When I was soloing, particularly on People of the Smoke I wanted to do something that was worthy in a way. I had him very much in mind and I was using the tremolo arm to do slightly unusual things. And it was a difficult technique using that at points: timing is crucial when you're chopping on the tremolo arm in the middle of a phrase that you're hammering on and hammering off in order to produce it.

That's - again - the borderline of what's really possible, but yeah those factors plus the fact that I was using three different electric guitars: I was using the Fernandes, I was using for the sustainer pickup; I was also using a Les Paul at times and I was using one of Brian May's invented guitars, a copy of his Red Special.

What was interesting about that was something that's very characterful of Brian - which is amazing considering that he developed this guitar with his father when he was about 15 - is the fact that if you've got some distortion of course and you put the neck pickup out of phase with all the others, you get this upper harmonic sound, almost as if you're playing an octave higher than you actually are. It makes the notes very well defined. You can hear that good effect on the track Wherever You Are.

It was a friend of mine who had one of Brian's guitars. He'd lent it to me, and I said, ‘yeah, marvellous guitar. Are you interested in selling it?’ And he said, ‘Oh, it's a present from my wife, bit tricky, that’, but then he came back to me few days later when he said, really what I'm looking for is a Les Paul, and I just so happened to have a Les Paul Custom with a guitar synth pickup on it. I said, ‘are you interested in this’? And he said yes. So we swapped.

GG: That's a good deal on his part, certainly! A Les Paul Custom, those are five thousand quid these days! (laughs) He did all right there!

SH: Yeah, I mean, there are those who say he came out, you know, ahead on the deal. But that isn't quite the point. I have another Les Paul that's my go-to one, my 1957 one, exactly the same model as the one Duane Allman used on Layla, which funnily enough I played a while back. That was like playing the same guitar as mine, it just felt exactly the same. I find that with Les Pauls, they're perhaps not as bright as the Fernandes, are not as bright as Fender, for instance. I guess I’m sounding very old-school here. I’m not saying to you about the latest this, that and the other. But I know there's so much fantastic stuff out there, so many wonderful guitars. It's kind of impossible to do it all.

GG: That's true, but you know, given my job, I'm playing all kinds of guitars every day of the week that come through into the headquarters, but the Les Paul is still the one I end up going for, so there's something about it, it’s just correct, isn’t it?

SH: Yes! Sure, there is something about it, and you know that people have produced wonderful sounds on those guitars. As I say, I think that if you brighten it, and at times I would be more inclined to use a tone booster when recording and also a Pete Cornish Iron Boost that he made for me many moons ago…that really makes…it turns one guitar into another guitar if you know what I mean? Suddenly, something starts to happen. I've started to use distortion units in series as well, stacking distortion units, and I've found that that can be very interesting, because when I'm recording, I'm not actually using amps. I'm using amps when I'm playing live, but I'm using stuff that's in the box. I'm using Apple Mac Logic, facsimiles, so that stuff that you're hearing I'd say most of it is not actually moving any air as we know it, so it's dispelling that myth, but it doesn't mean that in the future I won't go back to using amps. When I move house, I hope to be able to use amps again.

GG: Do you notice much in terms of, not so much even the sound, because I think we can all assume that the in-the-box stuff is as good as anything sonically to the end listener, but do you ever notice much of change in your own performance when you've got volume and, as you say, moving air as opposed to everything just coming into a set headphones?

SH: Well when I last had a studio, I owned one a few years ago, a purpose-built thing, and I was using a Marshall head that belonged to Ben Fennell and it was an old one and this thing really, you know, spits far, but I was hearing the sound of it coming through the floor when I was in the control room. We got virtually the same sound within the box and I said to Roger, ‘I can't believe that I'm not hearing this thumping through the floor’.

I was recording, re-recording the guitar solo or Musical Box on Genesis Revisited No.2 and I was thinking ‘This is a good sound. This is extraordinary!’ So, I was becoming less convinced by the argument that ‘oh it's got to move some air in order to be powerful’.

Certainly we did that with mellotrons back in the day with Genesis. It wasn't until we were literally moving air at Air studios with two stacks set up at one end of the room in order to make it fly on Fountain of Salmacis, but that made a huge difference, as opposed to merely being DI’d.

But I think it has changed somewhat since then. Things are more controllable, and the world of compression has become such an art in itself. And I, much as I appreciate technology, I'm a bit of a technophobe when it comes to working things, so I tend to be dependent on a third person. I'm not, I'm not techy. I just play the damn thing! (laughs)

What a perfect line to end our conversation on!

As ever, time ran out just as we were getting going, but we still managed to cover plenty of ground. Steve Hackett’s newest record, The Circus and the Night Whale, is available now wherever you get your music.

Steve has a busy year of gigs ahead, so make sure you head across to the official Steve Hackett website for details of where you can catch his excellent live show.

Our thanks to Steve for finding the time in his schedule for us, and to Sharon once again for putting us in touch.

You can find our three previous interviews with Steve at our Interviews page, alongside nearly 200 other exclusive artist interviews!

Thanks for reading, and we'll see you next time!