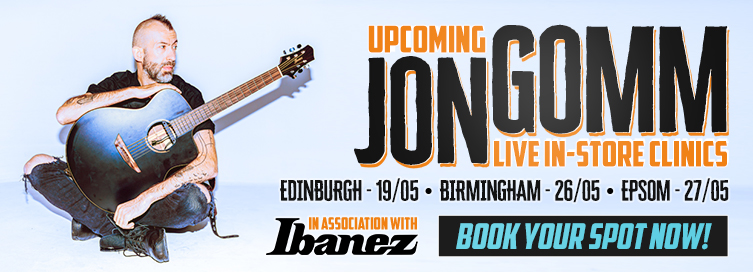

JON GOMM: Mental Health, Guitar Design and Moving to Ibanez

There’s never a dull moment in a conversation with acoustic guitar virtuoso Jon Gomm.

We’re barely five minutes into our Zoom call, and already we’ve covered subjects such as the victorian model village of Saltaire, where Jon’s been living for a few years (‘supposedly, the mill has the biggest room in the world’), documentary presenter and ex-Eastender Ross Kemp (‘he seems really nice but is inherently hilarious’) and the numerous merits of his hometown Blackpool (‘other towns, you can’t just go to the zoo in the middle of town. Blackpool’s amazing!’).

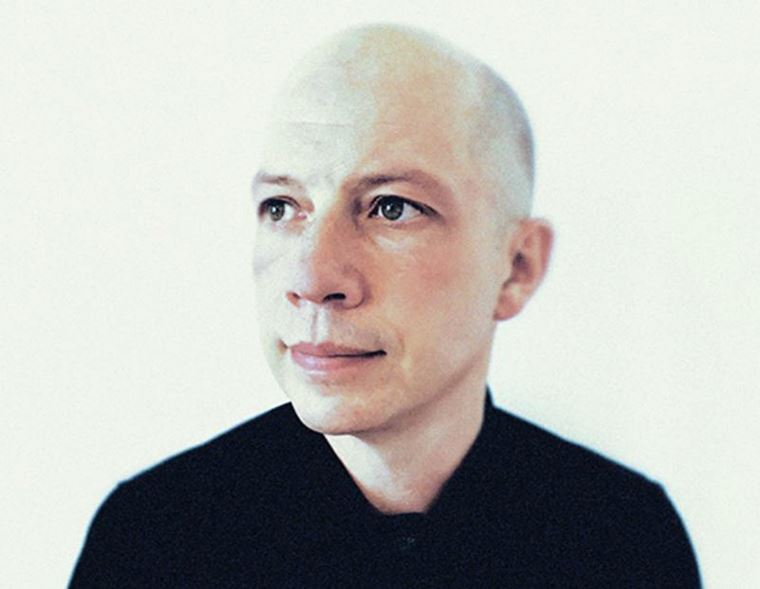

(Photo: Tom Martin)

He doesn’t waste a minute! We’re chatting to Jon ostensibly about his recent Ibanez Jon Gomm signature models - and we certainly cover a lot of detail regarding them - but knowing how sharing and open he is with his time and knowledge, we figured it would be well worth picking his brains about percussive acoustic guitar in general: how he goes about it, tips for writing, tone, the whole bit! If you get to have a one-on-one with someone who is an undoubted master of their craft, it’s worth going deep! We also touch on the influence of maestro Michael Hedges, the genius of Guthrie Govan, and why having nails isn’t a prerequisite for great acoustic playing!

There’s a lot more, so let’s get straight to it!

Jon Gomm Interview

guitarguitar: So, first of all: when last we spoke, it was the start of the pandemic, which is crazy because it was years ago now!

Jon Gomm: Yeah.

GG: And you were just about to announce the Ibanez guitar. Before we get to that, how has the intervening time been for you? How have you coped?

JG: So, it’s been amazingly kind of up and down, although probably down and up. During the pandemic, I was working on relaunching myself after having some big life-changing episodes, like becoming a dad and leaving the town I’ve lived in for 20 years. And some other stuff that was quite traumatic. Coming out of that, I decided, ‘Right, I’m gonna sign a record deal for the first time in my life’. I just wanted to make the best album I’ve ever made. Then Ibanez came calling, and it’s the kinda thing that, in the past, I’d say, ‘that’s not me’. Though I love Ibanez as a brand, I thought it was too big for me: it’s the kind of thing I’ve always shied away from. But no, I decided that I’m gonna do that stuff and really push it.

At the end of last year, I was able to do a tour, finally. Releasing the album as well, was really weird. And releasing the guitar was all muted and felt like it wasn’t quite real. But now, to actually be able to get out there and play the songs from this album on the guitar that we’ve designed, has been amazing, it’s just been incredible and I feel so lucky.

That first gig back, with new songs and a new guitar, it was scary, but then afterwards it was like, it all works! It’s all fine. I’m not at the point of saying ‘it’s good’ yet but after that first gig it was just like ‘thank god it all works!’ The songs aren’t shit, people don’t hate them and the guitar isn’t feeding back or unplayable or whatever, you know?

As the tour progressed, I was able to get into it, and the guitar sounds amazing. It just makes me want to play more and more now.

(Jon reaches for a guitar case) I don’t keep my guitars out: I keep them in cases.

GG: Why is that?

JG: I’ve just taken my JGM10 to get set up. I wanted to tweak it.

GG: Do you normally have a go-to guitar out of its case at all?

JG: Yeah, so I’ll have two or three out, and then everything else is just in a case. So, I’ve got two tens (Ibanez JGM10) and a five (the GJM5 model). It’s really pretty.

GG: Yeah, it’s absolutely stunning! See before we even start talking about that one, I’m interested in the whole story of a guitarist who is a Lowden endorsee, who goes to Ibanez. That takes bravery…

JG: I tell you, I had a pathway to follow. One of my best friends is an electric guitarist called Tom Quayle and he’s an Ibanez signature artist. He left a boutique company, and it’s a weird thing: people said to Tom, ‘Why are you doing that? It’s such a step down’. They make those kinds of assumptions, and it’s a strange thing because what I wanted to do was help develop a guitar with a mainstream manufacturer that was designed for modern fingerstyle, or percussive guitar. Something for those modern, progressive techniques. I wanted to do that with someone that was mainstream and could be accessible, in the sense that you can get it, you don’t have to order it and wait two years for it to be made! And also, it’s affordable, so my JGM10 is quite expensive, and there’s a JGM5 which is about half the price, and then there’s a series called the PA series, which are kind of based on my one. That’s a little bit how Steve Vai has the JEM and then there’s the RG series which is loosely based on that.

"Start your composition with the drums. When I come up with a cool guitar-drumming riff, that's when I get excited that I'm gonna have a really good song"

I just wanted to have an influence on mainstream acoustic guitar making and the direction that it goes in. People come up to me and say, ‘What guitar should I get?’, you know, they’re interested in modern fingerstyle and getting that sound. The answer was always, ‘I dunno, there’s nothing there! Save up for a Lowden and order one, or some other similar kind of thing’. That’s really, really sad and depressing because one of the things about guitar which makes it the most amazing instrument is that it is accessible, portable and affordable. It’s not like taking up the harp or, you know, the euphonium, where it’s going to cost you a fortune to be able to play it. It was really important for me to achieve that, and I was never going to be able to do that with a small, boutique luthier.

When I actually told Lowden, it was really emotional for me. I didn’t want them to be upset and think badly of me - which they don’t, they were really nice - but I was really sad about it. I phoned a dude at Lowden first and said, ‘Look, I wanted to tell you first, and then also ask your advice on whether you’d prefer me to tell George myself or you tell him’. In the end, I phoned George and told him. He was so lovely about it, and the nicest thing he said was ‘and you can always come back’.

GG: Aww, cool!

JG: Man, they’re so lovely. Anyway, yeah it was weird, leaving Lowden to work with a company like Ibanez. But then Ibanez are not some huge massive corporation: they’re not that big of a company and they really, really know their shit about guitars. Not just manufacturing, but in terms of acoustic guitars, it’s luthiery that they understand and they have very, very clever luthiers working for them who are able to do amazing things.

When they were asking me ‘how do you want this to sound?’ I thought the best way to express this was to get a load of nicely recorded samples of the best guitars in the world, most of which, if you wanted to buy, would cost you north of twenty grand. I sent them those samples and they were like: ‘Well, we like a challenge!’ (laughs) We’d already, by that point, roughly figured out the shape we wanted the guitar to be, but I was already thinking about sounds.

There’s loads of misconceptions people have had about guitars that I’ve learned over the years. I only understand it from the point of view of a guitarist. I could never be a luthier: I don’t have that kind of brain. But things that I’ve been told over many, many years by great luthiers are things like: people think that a guitar needs to be really light. It’s just bullshit! Also the thing about solid back and sides: some top luthiers laminate the backs of their guitars. The idea is that the back and sides’ job is to hold the solid structure of the guitar so that the top can vibrate as vigorously as possible. One approach is to think of the guitar like a snare drum so the top is loose, so it’s a bit like a banjo in that way.

But then, also, I used to think that the more the top vibrated, the better the guitar would be. It was actually Roger Bucknall at Fylde guitars who was saying to me, ‘No, that’s completely wrong!’ (laughs) If you let the guitar vibrate as much as possible, what’ll happen is, you’ll get a very loud attack, and then it’ll fade away very quickly, so it’ll have no sustain. Some guitars are built like that: flamenco guitars are often built with very light tops for a powerful attack and no sustain, so they are very aggressive sounding.

GG: That makes sense.

JG: The physics behind it all are really incredible. So, when I sent the sound samples to Ibanez, that’s when they started working on the bracing. I don’t know what they did or exactly how it was done, but they just came up with a unique kind of bracing pattern that would give the most bottom end without restricting the top end at all, but then not sound cold in the middle.

GG: So, this is bracing that hasn’t been used on any previous Ibanez guitar?

JG: No, they designed it based on the sound.

GG: And your guitar is a jumbo, right?

JG: It’s a jumbo, yeah.

GG: So it’s already got a lot of bottom end.

JG: Not necessarily. There’s loads of guitars out there that have no bass at all.

GG: Okay.

JG: Sadly! Yeah, there’s loads of big guitars out there that don’t have any bottom end. But what you will get is a lot of ‘boom’ with a big body. That’s usually because the back and sides are vibrating too much. As opposed to collecting the sound, they are trying to contribute to it, which doesn’t really help.

So yeah, the body shape: I came up with this shape roughly, and it’s asymmetrical which is unusual. I was actually asking luthiers stuff as I went through it. You know, there's no real reason why guitars have to be symmetrical. A guitar’s a big circle with a little circle, like a figure of 8. That’s roughly what it is, but there’s no reason for them to be symmetrical. I ended up talking to this guy who’d done a Phd on the physics of drums and he had a load of dums that were different shapes, they weren’t round. So, they were square or kidney-shaped, or just asymmetrical shapes. The shapes would change the harmonics, so you know how a snare drum has a note?

GG: Yeah.

JG: You can tune it up and down. So, if you make it a weird asymmetric shape, that note will often be less prominent within the sound. It’ll still have a resonant frequency but it’ll be kind of spread over a wider frequency range. If you imagine doing an EQ graph, and you suddenly do a sharp spike and a rounder, softer spike, by reducing the resonant frequency, you make it less like a big spike and more like a smaller, softer spike.

GG: How is that better for you as a player?

JG: It just means that you don’t get a big obvious feedback note. Obviously, my guitar’s not so asymmetrical that it’ll have that effect so dramatically, but the idea of the asymmetry was that I can have a really big body but it’s not uncomfortable to hold. The lower bout is smaller on one side than it is on the other and the waist of the guitar is not directly above where you put the guitar on your leg.

The weirdest thing is, when you look inside the guitar through the sound hole, it’s not exactly horizontal. All these little things, people won’t notice.

"Actually, I don't like the sound of nails on steel strings that much! Steel string guitar is already so trebly without the nails."

GG: I know what you mean! Does that change your playing position then, as you interact with it?

JG: It does a little bit, but it’s really hard to play a great big jumbo sitting down. It’s fine for me: I’m six foot-plus with really long arms, but for some people it’s a real struggle. My single favourite thing on the whole guitar design, which is so minor, is that the bridge is also set at an angle. Playing fan-fret multiscale guitars, I don’t actually like the frets but one thing I noticed, playing them, is that it opens up this area here (gestures towards lower part of guitar body), which is where people all do their kick drum. By opening this up, you get a way nicer, way better kick drum sound. There’s just a little bit more room here. There’s no reason why the bridge needs to be straight, so I just offset it by a few degrees. Nobody ever notices until I tell them!

GG: No, I didn’t! Does that also help with some of your special tunings, where there’s a lot of low notes? Does it help with tension?

JG: Not really, no, because the string’s not actually longer: it’s not a multiscale. It’s infinitesimally longer, so it’ll help a tiny, tiny bit. The reason it’s my favourite thing is because I came up with it: nobody’s ever done that, as far as I know. There’s other things, like the saddle’s a little bit wider, which all the top builders do, they all give it a double-width saddle. That’s so you can compensate it more, so you can get your intonation more accurate.

I absolutely love it: it plays amazingly and it sounds great. The big stress was the pickups, and that went right down to the wire. I spent two days in a studio testing pickups. I wanted to test them through a big PA so I could really check for feedback issues and stuff like that. There wasn’t anything that worked, it was so, so hard. I really like the Fishman Rare Earth with the humbucker and the mic, but I really wanted to have a contact transducer somewhere on the body too. I kinda didn’t want to use this mish-mash of different people’s pickups but, you know, people do that, it’s not that big a deal! Ibanez didn’t really care about that because they’d been used to having an electric guitar that might have a DiMarzio and then something else on it. I dunno, I just wanted it to be this complete system that one company was responsible for! (laughs)

So, it turns out that Fishman, a few months earlier, had brought out this pickup called the Power Tap, which is a bridge transducer. Ibanez said to them, ‘Please can you make us a system which has the Power Tap plus the Rare Earth humbucker and the Rare Earth mic in a three pickup system? They designed that, and it all runs off one 9v battery. It’s got two outputs…basically, it’s the dream! It’s like what I’ve been fantasising about existing for years, and trying to cobble together from all different pickup systems.

So, the two outputs: you got one stereo output and one mono output, and all three pickups go down all three routes. If you want to, you can just stick in a mono cable and it’ll blend them. There’s little blend wheels inside the guitar. So, if you don’t want that complication, you don’t have to have it.

GG: It seems to have been that, over the years, there hasn’t been one satisfying solution to acoustic guitar pickups. With the microphone, you get problems with feedback; with the magnetic humbucker, you can lose tone sometimes. So, it sounds like you have to have a complex combination, especially with the more adventurous playing styles. With the body, I notice that the cutaway area is where you often make your snares sounds, right?

JG: Yeah, sometimes, you slap inside the cutaway, yeah.

GG: Is that close to where the contact mic on this guitar even is?

JG: Oh no, the contact pickup’s on the bridge plate, inside.

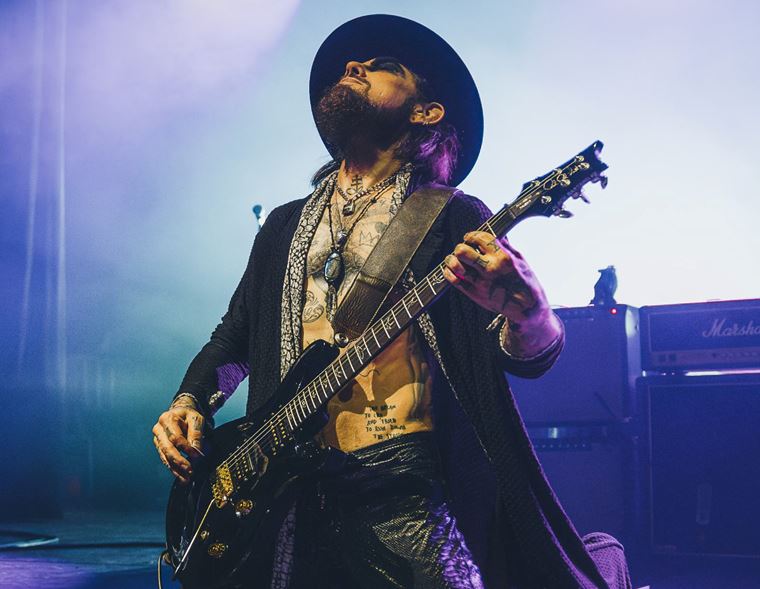

(Photo: Tom Martin)

GG: Ah, I see. I thought it might be like the Taylor Expression System.

JG: The microphone will pick up any treble, you don’t need to worry about that! You’ve got a tiny little condenser microphone in there which loves treble, but what’s hard to bring out is the bottom end. So, if you’ve got a transducer stuck on the bridge plate, firstly it’ll bring out your kick drum sound really well, and secondly, it’ll bring out the very low fundamentals from your bass notes. The magnetic pickup is always gonna struggle. Michael Hedges cheated and used steel strings on his acoustic guitars because otherwise he couldn’t get the bottom end out from the magnetic pickup he was using. But I don’t like playing steel strings on acoustic guitar: it’s weird, and most people don’t wanna make that sacrifice, but he did and it sounded amazing. I’m wondering now why I don’t do it! (laughs)

GG: Do you mean full on steel, as in, not phosphor bronze?

JG: He used proper electric guitar style - I don’t know exactly - but he used nickel steel electric strings. On acoustic guitar, it’s really hard for a magnetic pickup to penetrate through that thick layer of phosphor bronze that’s insulating the core of the string inside. Piezo’s a bit of a dirty word - people say, ‘Piezos, they’re shit’, or whatever, but actually any contact-vibrating thing has probably got piezo crystal inside it. They were originally used in seismographs for measuring earthquakes!

"When you hit the guitar, do it gently! Then people can hear the tone of the hit"

GG: That's some low-end there!

JG: Yeah! It turns vibration into electricity. Having that on the bridge plate means you get the kick drum, but you also get all that bottom end out of that string. The way that I EQ that as well is to pretty much bring out all the bass from it as well. That’s my bass pickup, really. Once you’ve mixed the pickups together and EQ’d them how you like them, you can get a really different sound to my sound, if you wanted to.

GG: Sure. It’s funny that you mention Michael Hedges. I know he wasn’t the first percussive, progressive acoustic player, but he was the first that I’d ever heard of, and he died not long after I started playing guitar.

JG: Yeah, as far as I know, he kinda was! He really started that approach. I mean, he wasn’t gonna play drum solos on his guitar but he was putting percussive work - striking the body of the guitar - but also introducing tapping. He kind of revolutionised everything: it really can’t be overstated. So, the tunings, the technique in terms of the quality of his fingerstyle technique and his extended techniques like using harmonics in a million different ways, using two-handed tapping in these incredibly unique, polyphonic ways…just really changing the nature of acoustic guitar. Without him, acoustic guitar wouldn’t be what it is now. It wouldn’t have taken that journey. It really can’t be overstated: he was a proper, proper genius!

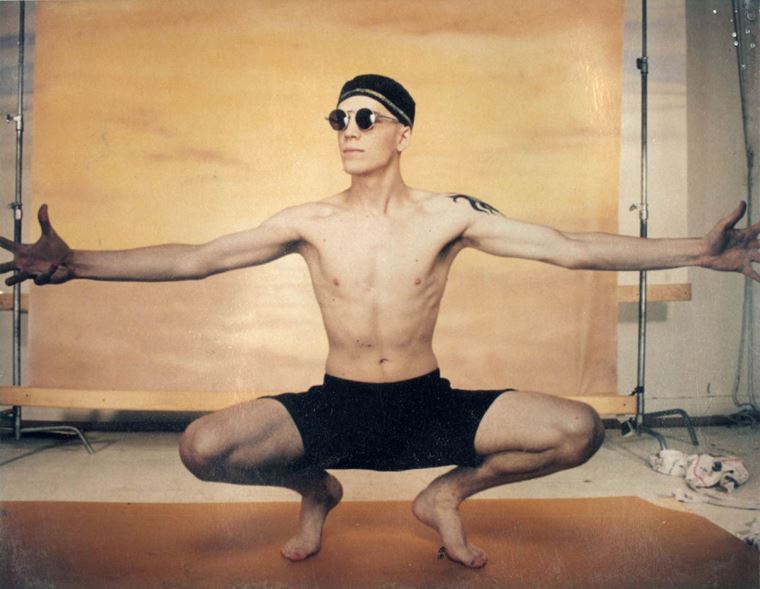

(Photo: David Galbraith)

GG: I concur!

JG: It didn’t come from nowhere, but he was very, very different to his influences.

GG: And there’s now Adrian Legg, Andy McKee…and you’re one of the most notable practitioners of…let’s call it progressive acoustic guitar playing.

JG: I love that, thanks man.

GG: Not at all, it’s true! Your playing could be intimidating, but it’s actually inspiring. You make me want to go and tinker about with my guitar rather than just going, ‘Holy shit, that’s too hard’. There’s a technique I watched you do that I wondered if I could ask about? I wondered first off if you invented this, or whether you found it somewhere. It’s so clever but also so obvious, and it’s on the song Until the Sun Destroys the Earth. You’re tapping with both hands, and your right hand, your picking hand is tapping but you’re also strumming at the same time as well!

JG: I don’t think I did invent that but what I did was, I saw a double neck player doing something like that. I saw a guy who plays double neck guitar - I can’t 100% remember - but he was definitely strumming the strings on one side and tapping out a melody with his left hand on the other side, on the other neck. So, I’m tapping a bass note and then strumming, yeah.

GG: No, see! It’s more than that: that makes sense to me, and this thing is different. (At this point, I scramble across to my guitar, stick it up towards my computer’s camera and try to illustrate what I’m failing to explain, whilst saying ‘you’re tapping over here, and you’re tapping here too and then strumming at the same time!’ Watching the video above will greatly aid understanding this particular moment)

JG: I totally know what you’re saying! So my left hand’s playing the lead and my other hand’s actually behind it, and they’re crossed over.

GG: Right, right!

JG: It looks very weird. I really like it! Do you know what? I don’t think I’ve ever seen anybody play like that before, so I’m happy to claim that I invented that! (laughs)

GG: Good! I think you should. Give it a name, you know? Haha!

"One of the things about guitar which makes it amazing is that it's accessible, portable and affordable."

JG: It is fun, I really love coming up with new ways to play and it is like you say, when you see somebody doing something that’s like a novel way to play, it is inspiring. It’s different when you just watch somebody who’s really good! (laughs) It can be wonderful but with guitarists, it can also be depressing, like, ‘Aw fuck, he’s so good!’ And there's plenty of people like that! If you look at Guthrie, who doesn’t even need a surname, he’s just Guthrie (laughs), as far as I know he hasn’t invented any new techniques, but he’s just so fucking good, you know what I mean?

GG: Yes.

JG: You watch him and you go, ‘I can’t do that’, and he doesn’t play any styles that I can’t play, he just does them all much, much better than I can! When you see somebody do something weird, you kinda go, ‘I could have a crack at that’. I might not do it exactly the same, but that’s an interesting approach, I can try that and do something with it creatively. I think that’s why it can be inspiring rather than just depressing!

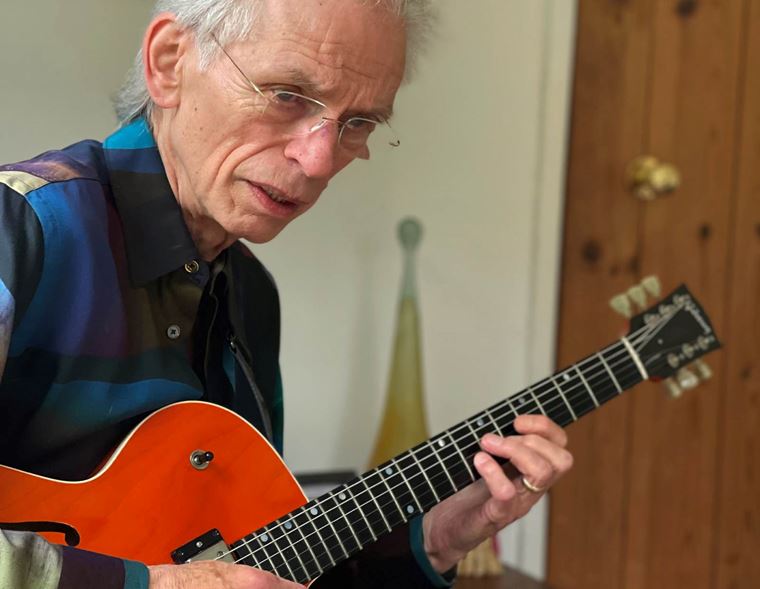

(Photo: David Galbraith)

GG: Now, a lot of people reading this will be players who would like to attempt a more percussive style and don’t really know where to start. Would you be able to offer one or two quick tips to get people using their guitar more like that?

JG: Yeah. So, the first tip - which is the most important of all - is that when you hit the guitar, you do it gently. There’s two reasons for that: one is the tone. Everything you’re doing with a guitar is striking wood with the flesh of your hand. The attack is always the same, no matter what part of the guitar you’re hitting, the initial attack sound is always going to be roughly the same, or similar. The harder you play any musical note, you get more attack but you don’t necessarily get more sustain afterwards. By hitting it harder, you’re making all of your hits sound the same. If you hit it softer, then people can hear the tone of the hit.

The other reason is: you’re less likely to break your guitar, which is nice!

GG: It’s important!

JG: Also, the guitar is naturally very quiet, so people often start out hitting their guitar too hard and the guitar’s so quiet, it sounds like somebody fingerpicking a guitar while your next door neighbour is building a shed! So, avoid shed building at all costs. And then, my other tip is, what tends to happen is, people will write something on the guitar, whether it’s strumming chords or fingerpicking, and then add some simple percussion afterwards. That’s totally fine, but unfortunately, what they end up doing afar too often is like a kick-snare-kick-snare pattern all the way through maybe not one song but several of their songs. It makes me want to eventually - eventually - claw off my own skin. (laughs) Try to avoid that! The best way to avoid that is to start your composition with the drums. I do that quite often, and when I’m writing arrangements on the guitar, I’ll start with the percussive element. Then, when I start to try to introduce notes, a lot of that drumming stuff that I’ve done might have to change or disappear. That’s okay, but by starting with the drums, you can be creative with the rhythm playing. It forces you to think about that creatively: ‘what groove am I going to play?’ I do that all the time, and when I come up with a cool guitar-drumming riff, that’s when I’m excited that I’m gonna have a really good song. So, that’s my advice!

GG: Do you delineate specific hands for specific ‘drums’, as it were?

JG: Never. Never, never, never. So, my most famous song, Passionflower, there’s points in that where, because of the nature of it, I’m kinda picking harmonics for the main riff with my right hand, but there’s a point where I reach across with my left hand and hit the kick drum. So, I reach across the guitar to the bridge with my left hand and hit a kick drum. It’s by far the weakest kick drum of the verse section - I can’t get it to sound exactly the same - but it’s a semblance of it. So, I never use one particular hand for a drum. Obviously, your right hand is gonna end up doing most of the drums because it’s closer to the body, but yeah, I don’t think like that.

There’s lots of places on the body you can use for drum sounds. What you choose for your ‘snare’ sound is really important. There’s different places where I play the kick on the guitar and it sounds different, but one that you can really change a lot is the snare because you can slap the side of the guitar for that kind of handclap sound, you can slap the strings for that sort of John Martin thumb slap, so that’s a good snare sound. Sometimes I’ll flick the guitar with a fingernail, sometimes I’ll do a little scratch on the guitar, which gives you a kind of 808 snare. You can do all kinds of snares.

GG: That’s good to know, because a lot of people will try to find a kind of prescribed formula, and it’s good to know that there’s no such thing. See your right hand? You’ll be using a plectrum sometimes and your fingers more often: how are your nails? Do you keep them long?

JG: No, I don’t do fingernails. I have a thumbnail, but that’s often for scratching. With the bass notes, I want to bring out a little bit of attack with it. Actually, I don’t like the sound of nails on steel strings that much. When Hedges did it, he had such an earthy, grunge tone anyway. It’s a strange thing, because nowadays, most modern fingerstyle guitarists use nails in a classical way. I found that astonishing: none of the guitarists that I grew up watching had nails, but they were mostly Blues guitarists. The first time I heard somebody play fingerstyle with nails on a steel string guitar, I couldn’t believe the sound of it, there was so much treble! So sharp, I really didn’t like it at all! There were two guitarists on that gig, and the other one was John Renbourn. He didn’t use nails, as far as I know, and he has this really beautiful warm sound. Steel string guitar is already so trebly without the nails, I just don’t really like it. Because I don’t have nails, I can do way more complex multi-finger right hand tapping.

"Michael Hedges revolutionised everything: it really can't be overstated."

GG: That’s interesting about John Renbourn; it was Steve Hackett who turned me on to him. He mentioned his acoustic playing and I didn’t know who he was at the time. All of that mediaeval stuff is great, and he did that thing where he moves his hand closer to the bridge for a more trebly sound, like a classical player but on a steel string acoustic. I don’t know if he was classically trained or not, but he’s doing that without nails.

JG: Yeah, I see what you mean. I’m classically trained as well but I don’t really have very good right hand classical technique. My right hand prefers playing more, you know, Jeff Beck’s hand shape. It likes to be flat: it doesn’t like to be arched at all, it hates it! I like to anchor, actually: the bass of my thumb on the bridge or on the body of the guitar or something. I was meeting Blues guitarists when I was ten or eleven years old and they were giving me lessons and stuff. My dad’s house was a kind of hotel for musicians so I’d get loads of lessons at breakfast! A couple of Blues acoustic guitarists showed me how to play slide, which I still do, though I haven’t gotten any better since they showed me how to do it! But yeah, the right hand technique I learned was so different to the classical technique I’d learned before and I preferred it so much. Often when I’m fingerpicking, I’m muting the 6th string, or even the 5th string as well, with the right hand. I don’t like it ringing too much down there: I like it as warm and kind of thick as possible. So, not necessarily killing the sustain, just muting the tone a little bit. So, the nails thing isn’t for me really. Saves a world of hassle as well!

(Photo: Marc Mennigmann)

GG: Big time! Now, I think we’ve covered pretty much everything I wanted us to touch on! I suppose the only thing left is to sum things up: you’ve had the record out, the guitar out, but because of the pandemic, you haven’t been able to give them the push that you wanted.

JG: Well, we did, but I wanted that physical, in-person thing.

GG: Okay, so now that things are - touch wood- starting to change for the better in terms of touring and so on, what does the year ahead have in store for you?

JG: I’ve got some overseas trips that I'm still trying to work outl, that’s all very sketchy at the moment. But I am working on new stuff. I don’t want to say too much about it because I don't want to jinx it! But it’s also a bit different from stuff I’ve been doing recently. Having the new guitar has made me want to just have fun on the guitar, so I’ve been doing stuff that is just fun, which I haven’t done for ages. The past several years, everything that I do writing-wise or arranging-wise, has always had to have some sort of strong meaning, significance and depth to me. I just want to have a bit of fun now!

I was on tour with Don Ross once, and I was having a hard time, as I often have done in my life. I was talking about the music I was playing, and a lot of what I played then, at that point, was stuff that was really dark, you know? It really took it out of me, playing it on stage. It was quite brutal, but I can’t not put everything into each song. But Don’s had a hard life in many ways, he’s had really bad stuff happen to him in his life. I asked him why he never put that stuff in, like, he never plays music that reflects the bad things. You wouldn’t think that. I said, ‘How come you don;t have all that dark stuff in your music?’ He said, ‘Well, because I wanna feel good when I’m playing music!’ When he said that to me, it was about five years ago and that had literally never occurred to me! (laughs) Oh yeah! Oh yeah, that’s quite a good idea, that!

Anyway, I’ve had stuff that I needed to say. When you write music that’s about personal stuff, it’s not like you’re trying to say it to anybody else, it's just a way that you can say it to yourself. It's like, ‘Okay, I’ve dealt with that: I’ve put it into this song that explains it to myself how I feel about that’. Now that I’ve done that, I am just gonna do some stuff which is fun!

Our time was drawing to a close, so we said our goodbyes and left each other to our respective Friday evenings. Jon was as refreshingly open and honest as ever, and it was lots of fun to quiz him about his quite magnificent playing. This conversation took place some weeks previous to publication, so it’s well worth checking the Jon Gomm website for up-to-the-minute updates on his touring plans.

We’d like to thank Jon for giving us such a detailed and entertaining conversation. We’ll see him - and you - soon!